We need to talk about Brexit. July should have seen a Brexit deal ratified at the European Meeting of ministers. That did not happen. And, to state the obvious, at the time of writing, an agreement has not been made. And, with PM Johnson publicly saying that no deal would be a ‘good outcome’, the prospect of the UK starting 2021 trading on World Trade Organisation (WTO) terms with the EU and the UK treated as a third country, is something both individuals and firms need to prepare for.

The potential for disruption

Whilst many countries do trade with the EU on WTO terms, it is the change in a much closer relationship that spans 47 years that will be disruptive. New ways of doing business with the EU will take some getting used to. Even if a trade deal is struck this year and implemented by 1st of January 2021, some things will change. The EU will insist on the full spectrum of customs controls on visible goods entering the EU from the UK. Excise duty and VAT payments will be expected, and checks needed to ensure that products coming from the UK meet EU regulatory standards.

In the absence of a deal in services, which is seen as even more unlikely before year-end than one on visible trade, the UK will have to demonstrate compliance with EU service standards. Recognition of UK professional qualifications, and road, rail and air licences will end, and no deal has yet been done on UK/EU trade in financial services. The UK’s approach to goods entering from overseas, including from the EU, is also still to be worked out, although the signs are that it will be less stringent than the EU regarding imports to the UK.

For individuals, UK citizens will lose the right to work in the EU, driving licences will no longer be recognised and travel visas for stays of over 90 days in any 180 days will be required. As well as the individual loss of educational qualification recognition, the guarantee of no mobile roaming charges will also end.

A brake on economic growth

What we seem to be looking at is not a conventional free trade agreement that would minimise disruptions to the UK economy and, in that sense, the outcome will almost certainly hurt growth. One thing for sure is that it will disrupt corporate supply lines and disrupt trade. I seem to recall a phrase about ‘the easiest trade deal in history’, and that there would be no disruption being uttered at some point about the UK’s ability to strike a beneficial trade deal with the EU. It doesn’t seem so easy now.

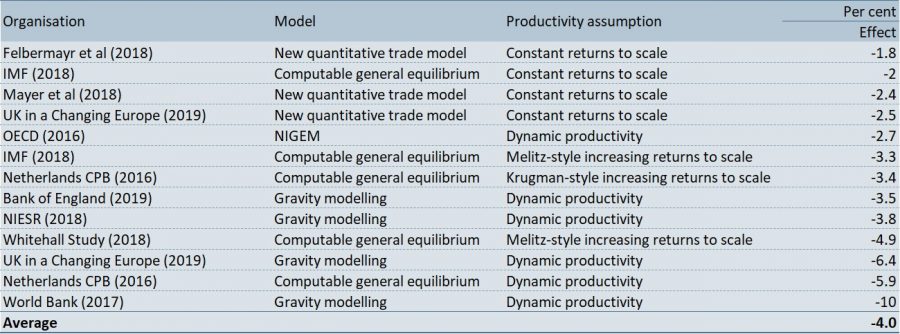

Surveys indicate that businesses are anticipating that Brexit will harm the UK economy over the coming years. Table 1, for example, shows a consensus that even a free trade agreement would reduce business investment spending compared to if the UK had opted to remain in the EU.

Anticipated risk

Chart 1 highlights the top three risks businesses consider to their growth prospects over the next three years (two risks shown). COVID-19 tops the list of concerns followed by global political risk and Brexit.

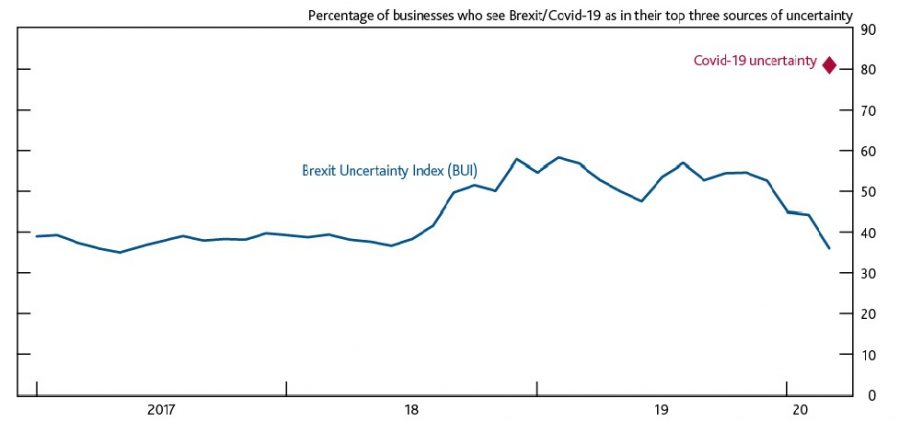

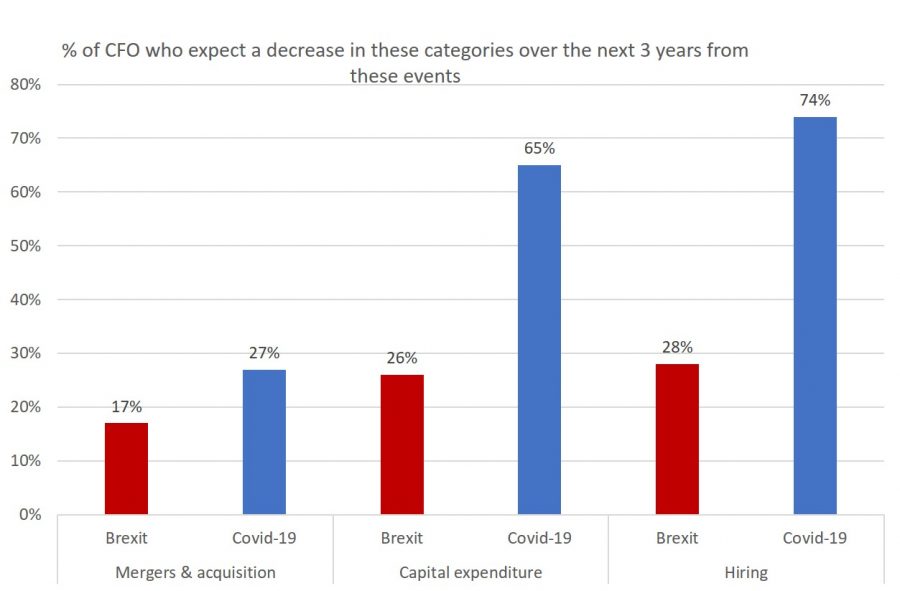

Whilst Brexit has fallen into third place since mid-2019, which may reflect greater certainty that it will happen and a focus on the nature of the deal, nevertheless, as Chart 2 shows, uncertainty remains high. This uncertainty is translated into business intentions to decrease spending in three critical areas: mergers and acquisitions, capital expenditure and hiring as a direct consequence of Brexit.

If these intentions become actual decisions, this will cause a slowing of economic growth through higher unemployment, so less consumer spending, and higher failures, so less investment spending. Weaker growth will be the outcome. In consequence, there will be more pressure on the fiscal deficit and downward pressure on interest rates.

COVID-19 notwithstanding, nobody can afford to ignore the progress or otherwise of Brexit negotiations over the coming weeks nor the effects of the different potential outcomes.