Since the appearance of COVID-19, there has been a massive decline in global trade. World Trade Organisation figures suggest that it could fall be about a third this year. But some context is required here. The reduction is taking place mainly due to the voluntary shutdown of the global economy to fight the Coronavirus. This was not a crisis created by a problem either in the real economy or, as was the case with the last global crisis, in the financial sector, but by a health emergency.

Moreover, globalisation did not cause the global health crisis and deglobalisation will not fix it. In fact, globalisation is required in order to be able to provide for the speedy spread of ideas, knowledge and medical products that will fix it. For those who think otherwise, the lesson from the pandemics of the past that killed millions of people is that it took many hundreds of years of advances in science and technology around the world before effective methods were invented to at least alleviate their effects.

Global supply chains

An argument by those who oppose globalisation, however, is that there was not enough diversification of manufacturers of essential equipment to fight the virus, which led to so many deaths in some countries. A couple more points worth noting is that arguments about supply chains being too far from local demand misses the point about supply chains. Diversity of production is not just about producing locally; it is also about producing internationally, from different companies in different countries.

In other words, less reliance on one supplier does not have to lead to a reduction in global trade because the diversification of suppliers should be both within countries and between them.

For one thing, you risk handing monopoly power to a local producer who may charge more than any international supplier. For some industries, and particularly for those in small countries, making sophisticated products with several inputs, it is simply not efficient to have all of the inputs manufactured locally, as it would make production uneconomical. Even large countries would face the same issue of not being equally efficient in producing everything.

Moreover, even local supply chains can be disrupted by bad weather, other accidents of nature and by human-made disasters. Reducing the capacity to be able to scale production elsewhere in the world to meet sudden changes in demand, and disruptions to supply to individual countries, would not help anyone.

The globalisation comeback

Of course, the death of globalisation has been foretold many times, but it has yet to occur and for a good reason: it has led to an unprecedented increase in global living standards.

So, once the pandemic is over, and the lockdown ends – and at some stage, it will – there will be a sharp bounce back, though it is unlikely on current trends to be back to its previous path.

One reason for this is that, with China shutting down early – and noting that it accounts for nearly 30% of global manufacturing activity – companies around the world have felt its downstream effects. Moreover, the closure of seaports, airports and travel more generally would naturally have contributed to a sharp reduction in global trade. Fundamentally, the sharp decrease in global demand would have naturally led to a sharp decrease in supply. The question is to what extent this will persist once the shutdown ends or is reversed.

Sharpening of existing tensions

There were many challenges to global trade before COVID-19 hit, but the pandemic has, by exposing and attenuating existing issues, undeniably accelerated the point of crisis. For instance, there was already a trade dispute between the US and China. For years, there have been arguments that China was not reciprocating the same freedom of access to its markets as it expected into the markets of those it was trading with.

In response, under former President Obama, the US administration tried to create a new trade zone encompassing countries in Asia but excluding China. But there was also a transatlantic trade dispute going on between the US and Europe on cars, an oil pipeline linking Russia to Germany and a proposed European digital tax on US tech giants. These haven’t gone away.

The question remains whether these will lead to a repeat of the ‘beggar thy neighbour’ policies which created so much of the conditions for the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The threat of nationalism

It is folly to think that a return to the world of nationalism and ‘Great power politics’ would solve the problems of today’s world. Instead, it would result in a return to the chaos and continued conflicts that occurred at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, which would create vastly more serious problems than we currently face. Fixing today’s issues of climate change, technological change, of increasing risk episodes, of ageing but rising populations, requires more cooperation not less.

Let us remind ourselves what is at stake: it is no less than the global trading system, which has led to the unprecedented prosperity that has spread around the world in the last 73 years. This has resulted in the fastest increase in living standards for the largest number of people hitherto seen in human history.

Supporting rising living standards

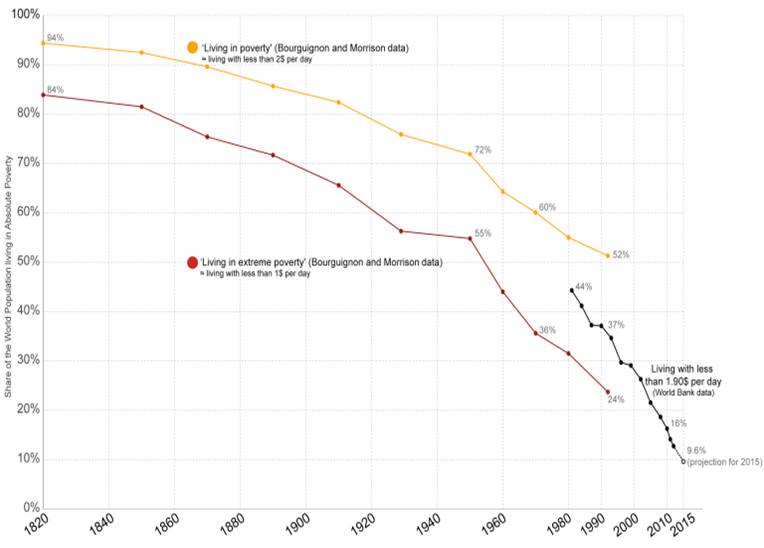

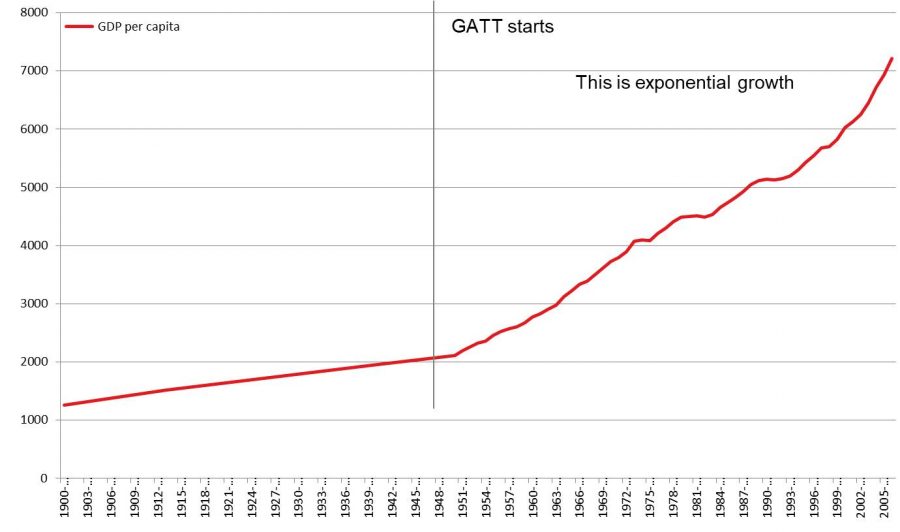

Billions have been pulled out of poverty. More needs to be done for sure, but the progress has been phenomenal. We can draw a direct link between increases in global per capita incomes since the General Agreement in Tariff and Trade (GATT) was initiated in 1947 and the fall in global poverty that occurred over the period as a result of rising living standards.

I’d describe this as down to the spread of economies of scale from increased productivity, which has reduced production costs, and therefore cut prices to consumers and left them with more money left over to spend on other goods and services. This directly led to increased profitability for companies selling products into a vastly bigger global market than their domestic ones. In short, everyone can gain.

The reality that this may not necessarily mean that everyone gains at the same rate is down to the way that tax systems work in different countries to redistribute the gains from globalisation and technology from those who gained the most to those who gained the least.

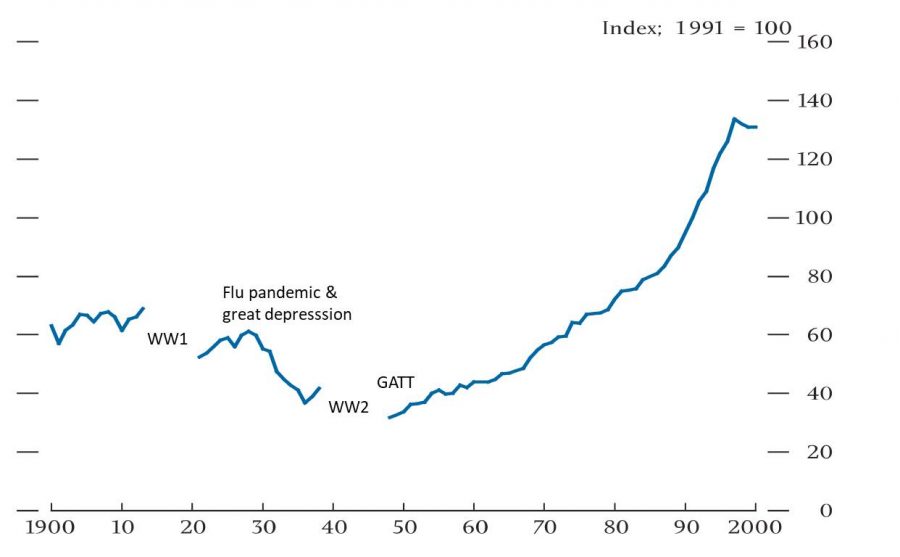

Three charts illustrate the points made about globalisation. A considerable increase in per capita incomes has taken place since WW2, with global trade helping to drive faster economic activity, and that resulted in the sharp fall that occurred in poverty around the world. More prosperity and opportunity also helps promote greater stability and security for everyone.

Global GDP, $ nominal