Rachel Reeves’s budget statement in response to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) update aligned with what was widely flagged ahead of the event. However, it highlighted just how little room there is for manoeuvre in the government’s fiscal projections and how vulnerable the plans are to unfolding events. Admittedly, huge geopolitical and geoeconomic changes have been and are occurring under the new political leadership in the US.

The global economic landscape is in a state of flux as the US, under its current President, redefines its role in international institutions and sparks a trade war. These actions, such as the imposition of tariffs on steel and the potential extension to other goods, are expected to disrupt trade flows, dismantle supply chains, and breed uncertainty. The UK’s open economy is likely to be significantly impacted by these developments. For instance, the recently announced tariffs on car imports to the US, if implemented, could potentially shave off 0.3% from the UK’s GDP, given that 4/5ths of its car exports are destined for the US. This underscores the looming possibility of tax hikes, increased borrowing, or further spending cuts in the Autumn Budget, as all are under the shadow of uncertainty.

The recent revisions to the fiscal projections underscore the influence of both domestic and international events on the UK’s budget. This further highlights the critical role of trading agreements in shaping the country’s economic future.

Budget arithmetic – an update

In terms of the fiscal arithmetic, the reserves of £9.9 billion forecast in October spending plans were depleted due to a downward revision of growth from 2% to 1% for this fiscal year and higher-than-expected interest payments on government debt. The Chancellor restored the reserves to £9.9bn by reducing the welfare budget by approximately £5bn, decreasing the size of the civil service, and implementing further efficiency gains. Additionally, defence spending was increased by £2.2bn. In contrast, the decision to raise overall spending on it to the 3% GDP target was deferred, as achieving that target would require an additional £25 billion.

Since a £10bn reserve is much less – one-third – of the usual amount that UK governments have set aside for emergencies, it is especially vulnerable given the global economic backdrop. The risk is that by the time of the next annual budget in October, the Chancellor could return to where she started with insufficient reserves, and once again, the pressure would be on to find spending cuts, raise taxes or borrow more. In the interim, a departmental spending review will be announced in June, which could also pressure the Chancellor to find more money to spend.

Notably, the Chancellor has not changed the tightening of departmental spending, which is evident in the last two years of this current Parliament, where departmental expenditure is projected to slow sharply to some 1% pa apart from the protected health and education departments. So that is one of the other issues left to a later budget statement in the hope, one presumes, that economic conditions improve; otherwise, there will be cuts in non-protected department spending.

Economic growth

The OBR’s projections include some optimistic assumptions. Although it has halved its growth forecast for 2025 from 2% to 1%, growth from 2026-2029 is projected to be 1.75% per year. However, since 2008, GDP growth has averaged 1.2% annually, reflecting the periods of financial crisis and pandemic. 1.75% pa looks challenging to achieve. So, built into the OBR’s own growth forecasts is the likelihood that they aren’t achieved and, therefore, that the tax revenues from that are also not achieved.

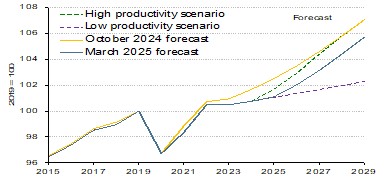

Productivity assumptions made by the OBR are also overly optimistic. Recent figures show productivity growth struggling and barely growing, and unlikely to recover as strongly as expected by the OBR; see the chart below. The low productivity line in the chart seems most likely, growing at its 10-year average rate of 0.3% until 2029 instead of the assumed increase of nearly 1%.

The importance of productivity

Productivity is crucial for growth, which depends on the workforce’s skills and investment quality. UK investment spending by businesses and the government has been poor and erratic with forecasts showing modest and slowing growth in the forecast period ahead, as shown in graph b. Credible plans are needed to boost business investment by lowering capital and labour costs and boosting government investment in infrastructure. The OBR notes that increased infrastructure investment will also support growth, including housing, energy plants, and commercial buildings, where needed.

Unfortunately, there are simply not enough announcements of these sorts of initiatives, which would boost economic growth in the long term. This means the OBR forecasts, which show a strong rise, look unlikely to be achieved. Economic growth would be slower than in the projections, which would put the Chancellor’s spending plans at risk from a lack of growth in tax receipts.

The Chancellor needs to concentrate on increasing productivity by accelerating the implementation of housing reform and widening its remit with improvements in apprenticeship schemes, changes to technical colleges, and technical qualifications. This shift aims to provide more skills-based courses for individuals who prefer not to attend university, replacing some of the current emphasis on academic qualifications. That’s a lot to do, but they have a roughly 160-seat Parliamentary majority, which typically takes at least 10 years to lose. It allows both time for long-term planning and reaping the benefits in the next Parliament, see chart c.

Debt woes

One notable point from this budget is the rise in interest payments on debt, projected to reach £130bn by 2028/29, up from £105bn this year. This amount surpasses defence and education spending, with only welfare and healthcare budgets being larger.

This situation exposes the UK to potential increases in long-term interest rates, highlighting the pressure on public spending. This strain is primarily due to the pandemic and compounded by slow productivity growth amidst rising demands for services from an ageing population.

Indicative of these pressures, the total debt interest payment has increased from some £40bn some 14 years ago to £105bn today. And debt is projected to hit £132bn by 2030. That may be why the Chancellor pushed the increase in defence spending to 3% in the next Parliament. It isn’t easy to see where the £25 billion extra required will come from at any point in this current Parliament. The UK is also vulnerable to events taking place in Ukraine and commitments it may make towards its defence and security arrangements following any ceasefire.

Finally, some good news

Still, the Chancellor had some positive news to share during the statement: annual consumer price inflation slowed from 3% in January to 2.8% in the year to February. This increases the chance of an interest rate cut at the May Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting, which could help the economic recovery, mitigate the risk of slower growth, ease the burden on businesses of potential trade wars, and partially offset the scope of the fiscal tightening announced in the budget along with the downward revision to growth.

It’s the least the MPC should do as downside risks for the UK economy mount. Despite very similar economic growth rates and not too dissimilar inflation rates, the Bank rate in the EU is 2.5% compared with 4.5% in the UK.