Demographics and Growth

The UK faces demographic pressures, labour shortages, and modest productivity growth. These pressures stem from an ageing population and low birth rates, both of which shape the workforce. Inward migration has been a significant, though often underacknowledged, driver of economic performance. It remains one of the most politically contested topics in public debate.

This article sets aside political considerations to focus on empirical data and economic analysis. Its aim is to examine how migration interacts with labour-force growth, productivity, and sectoral capacity, and to assess evidence of its recent role in the UK economy and the consequences for future policy choices.

Over the past two decades, the UK has relied on inward migration to sustain labour-force growth, even as domestic demographic trends move in the opposite direction. The working-age population is barely expanding, fertility rates are low, and the number of retirees is rising. These trends are common across advanced economies, but their economic impact is especially clear in the UK, given subdued productivity growth and persistent labour shortages. In this context, migration has been a stabilising factor, supporting economic output, easing bottlenecks, and maintaining the capacity of vital public services.

Migration’s Contribution

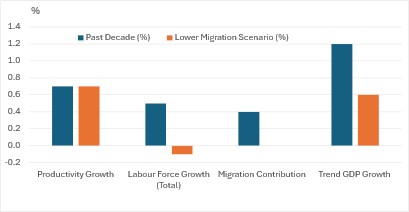

The significance of migration is clear in the fundamentals of long-term economic growth. Trend GDP growth depends on two main factors: labour-force growth and productivity growth. A larger labour force increases total output, while higher productivity lets each worker produce more per hour. In the UK, productivity growth has averaged about 1% in recent years, much lower than pre-financial crisis levels. Labour-force growth has added about half a percentage point to trend growth, with migration responsible for much of this. Without migration, the UK’s labour force would be stagnant or shrinking, reducing trend growth to 1% or less. This pattern is seen in other advanced economies too.

Numerous advanced economies, such as Germany and Canada, increasingly depend on inward migration to counteract ageing populations and declining birth rates. For instance, Germany’s recent labour-force growth is primarily attributable to migration, whereas countries with limited migration, such as Japan, are experiencing workforce contractions and slower economic growth.

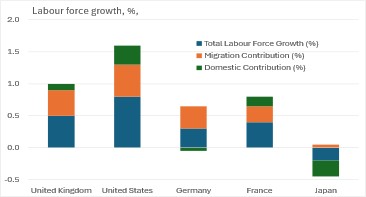

Migration accounts for about 60% of total labour-force growth across the G5 economies, making up the majority share in almost every country. This shows that the UK’s reliance on migration is not unusual or excessive; it is typical of all advanced, ageing economies. In the United States, total labour-force growth of about 0.8% per year includes 0.5 percentage points from migration, supporting trend growth of 2.5%. Without migration, the labour-force contribution drops sharply, reducing trend growth to around 1.8%. Key sectors such as healthcare, construction, logistics, agriculture, and technology depend heavily on migrant workers, and migrant households help stabilise the US dependency ratio.

Germany provides an even clearer example of migration offsetting demographic decline. Domestic labour‑force growth is now negative, and stylised estimates suggest that total labour‑force growth of 0.3% comprises 0.35 percentage points from migration. With migration, Germany’s trend growth is around 1.2%; without it, trend growth falls to 0.4%, showing a shrinking working‑age population and acute shortages in manufacturing, engineering, healthcare, and elder care.

France’s demographic profile is more balanced, but migration still contributes 0.25 percentage points to labour‑force growth and around 0.4 percentage points to trend growth, supporting sectors such as hospitality, construction, logistics, and personal services. Japan illustrates the consequences of limited migration. Domestic labour‑force growth is sharply negative, and even modest migration inflows cannot offset the decline. With migration, trend growth is around 0.7%; without it, it falls to 0.2%, highlighting the financial stresses created by rapid ageing.

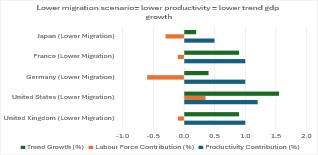

Across the G5, migration usually provides between one-third and one-half of total labour-force growth, adding about 0.4 to 0.8 percentage points each year and a similar share to trend growth. Conversely, in a lower migration scenario for the G5, one can see that overall growth is lower, partly because of weaker productivity gains, see chart 2.

Presenting these numbers as shares highlights the central role of migration in sustaining economic capacity more clearly. This shows that the UK’s reliance on migration-driven workforce expansion is part of a wider trend among developed nations facing similar demographic issues.

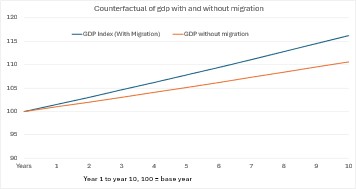

Although growth rate differences may seem minor, they add up over time. A country growing at 1.5% annually will be much larger than one growing at 1% after a decade. Over this period, the difference is about £150 billion in extra output, equal to the entire annual education budget. In practical terms, this is the scale of resources missing from the economy and unavailable for funding schools, teachers, and vital services if growth stays lower.

The resulting half-percentage-point gap means reduced tax revenues, tighter fiscal constraints, and slower improvements in living standards. As demands on public services, especially health and social care, rise, this distinction is critical. By supporting labour-force growth, migration extends the economy’s growth potential and reduces reliance on productivity gains.

Fiscal Pressures

Demographic trends reinforce this argument. The UK’s dependency ratio, or the number of dependents relative to the working population, is rising as the population ages. Without migration, this ratio would rise faster, increasing the fiscal burden on the working-age population. Migration eases this by bringing younger workers into the labour force, expanding the tax base, and supporting the financial needs of an ageing society. This long-term dynamic can shape fiscal policy for decades. A higher dependency ratio means higher taxes, reduced spending elsewhere, increased borrowing, or a mix of these. Migration helps ease these fiscal pressures.

The long-term consequences are clear when comparing different growth paths. An economy growing at 1.5% annually will be about 16% larger after ten years, while one growing at 1% will increase by only about 10%. The resulting 6% GDP difference is significant and affects public-service funding, debt sustainability, and improvements in living standards. While migration is not the only factor in long-run growth, in an ageing society with limited productivity gains, it remains one of the few reliable ways to support the labour force.

Sectoral Impacts

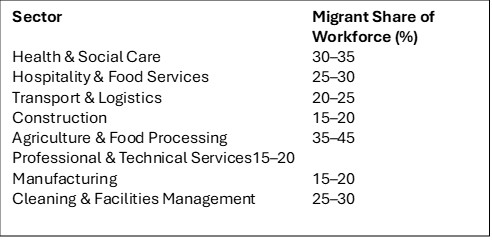

A clearer understanding of migration’s economic impact comes from examining the sectors in which migrants work. The UK labour market is uneven, with migrants concentrated in labour-intensive sectors, those with worker shortages, or those needing skills that are scarce domestically. These concentrations matter because they affect the UK’s productive capacity, the strength of public services, and the economy’s ability to adapt to demographic changes. Health and social care provide the most prominent examples. Migrants constitute a significant proportion of nurses, doctors, care workers, and support staff. For example, approximately 16% of NHS nurses and 36% of doctors in England are foreign nationals, and migrants represent a considerable share of the adult social care workforce.

Their contributions are vital to the daily operations of the NHS and the broader care system. Without them, waiting lists would grow, care homes would face operational challenges, and the system would struggle to meet rising demand from an ageing population. Domestic recruitment alone cannot fill these roles at the needed scale, and UK demographic trends are widening this gap. The health and care system is already under strain; further reductions in migration would worsen these pressures.

A comparable pattern is apparent in hospitality and food services, where migrants are essential to the operation of restaurants, hotels, and the tourism sector. These positions are frequently difficult to fill domestically due to unsociable hours, seasonal fluctuations, and pay structures. Migrant workers supply the flexibility and capacity required for the sector to function at scale. If migration declines, the effects ripple quickly to everyday life: fewer baristas behind the counter mean longer queues at coffee shops and higher prices for a morning latte.

Restaurant staff shortages may cause reduced opening hours or even closures, making it harder to book a table or driving up the cost of a simple meal out. Hotel stays in major cities and regional destinations become less affordable and harder to find, while local high streets lose some of their vibrancy. In practical terms, a decline in migration translates into longer waits, higher prices, and fewer choices for consumers. More broadly, a more volatile, less competitive service industry also has important consequences for employment and regional economies dependent on tourism.

Transport and logistics provide another clear example. Post-pandemic shortages of HGV drivers and warehouse staff disrupted supply chains and added to inflation. Migrants are critical to keeping goods moving nationwide, from supermarket shelves to manufacturing inputs. When labour availability drops, the system becomes more vulnerable and higher costs spread through the economy. Supply-chain resilience depends on a stable, adequate workforce, and migration is key to this stability.

In construction, the link between migration and economic capacity is clear. The UK’s housing shortage is partly due to labour shortages. Migrants fill skilled and semi-skilled roles, enabling the delivery of new homes, commercial buildings, and infrastructure. Less migration would slow construction, raise costs, and worsen affordability. Each 10 per cent drop in construction labour can add up to three months to average build times, turning an abstract shortage into real delays for families waiting for housing. Major infrastructure projects, already delayed, would face more limits, affecting transport and energy investments. The UK’s ability to meet housing and infrastructure needs depends on a large, skilled labour force.

Agriculture and food processing depend even more on migrant labour. Seasonal work is critical for harvesting and production, but domestic workers rarely fill these roles at the needed scale. Without migrant labour, crops go unharvested and food output drops. This leads to higher prices, more volatility, and greater reliance on imports. The strength of the UK’s food system is closely tied to access to international labour. Reducing migration would increase the UK’s vulnerability to supply disruptions and price rises.

At the higher end of the skills spectrum, professional and technical services – including engineering, IT, research, and science – also depend heavily on international talent. These workers contribute to innovation, patents, start-ups, and high-growth firms. They are key to the UK’s goal of maintaining a competitive, knowledge-based economy. Restricting migration in these fields would reduce the nation’s innovative capacity and competitiveness in global markets. The UK’s leadership in sectors like fintech, pharmaceuticals, and advanced engineering depends on access to global talent.

Less visible sectors like manufacturing, cleaning, and facilities management also rely on migrant workers to maintain capacity and service quality. Manufacturing depends on migrants for production and exports, while cleaning and facilities management are essential for hospitals, schools, offices, and public buildings. Without migrant labour, service quality would fall, costs would rise, and these sectors’ resilience would weaken.

These sector patterns show a clear reality: from crops to code, migrants fill the UK’s most critical labour gaps. The sectors most dependent on migrant labour support public services, infrastructure, supply-chain resilience, and long-term competitiveness. They are also areas where domestic labour cannot expand quickly or at the scale needed. So, reducing migration would not only tighten the labour market but also hurt productivity, inflation, and long-term growth.

Productivity and Inflation

The demographic view further supports this argument. Without inward migration, the UK’s working-age population would shrink. Migration offsets this, leading to modest growth and supporting labour-force expansion. This matters because a shrinking working-age population reduces the economy’s ability to produce goods and services. Labour shortages push wages up faster than productivity, raising business costs and prices. Ageing economies also tend to invest less, which slows technology adoption and reduces productivity growth.

Myth-busting: Migrant Workers and Productivity

A common misconception is that an influx of migrant workers lowers overall productivity. Evidence shows the opposite: demographic ageing, not migration, is the real challenge to productivity. As the working-age population shrinks and more resources go to retirees, investment and innovation can stall. Migrant workers help cushion productivity pressures by sustaining the labour force. However, this cannot continue forever, of course – with strains in the social and political arena – and long-term decisions will be needed when this option is no longer viable.

Meanwhile, labour and capital are increasingly in demand in lower-productivity sectors, such as health and social care. But this is where measuring productivity is more difficult say than in a manufacturing process. Hence, while migration is sometimes blamed for lower productivity, the rise of low-productivity jobs is mainly due to demographic shifts. Without migration to offset the decline in the working-age population, at least in the short term, the economy faces weaker supply growth and more inflationary pressure.

Policy Choices

The broader implication is that any credible UK growth strategy must account for demographic realities. The population is ageing, productivity growth is modest, and labour shortages are widespread. In this context, inward migration has been a major driver of growth, productivity, and fiscal sustainability. Reducing migration would not just tighten the labour market; it would also lower long-term growth, weaken productivity, and increase fiscal pressures. If migration falls, which lever would be used to address these consequences: raising taxes, increasing borrowing, or cutting public services?

This analysis does not suggest that migration policy cannot or should not change. However, the economic consequences of reducing migration are significant and lasting, especially for sectors supporting public services, infrastructure, and long-term competitiveness. Alternatives such as greater automation, domestic upskilling, and productivity reforms may help address labour shortages, but they are unlikely to reach the scale or speed needed in the short term. Without alternative labour sources or a major productivity surge, the economic costs of reducing migration will be greatest where capacity is already tight.

So, the UK faces a fundamental decision: it can acknowledge the economic significance of migration and integrate it into a long-term growth strategy, or it can reduce migration and accept the consequences of slower economic growth, increased fiscal pressure, and heightened strain on public services. Evidence indicates that pursuing both accelerated growth and reduced migration is not feasible. Therefore, policymakers must confront challenging decisions. Explicitly articulating the trade-offs associated with each policy option can enhance the legitimacy of the chosen course of action.