The Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) November 2025 Economic and Fiscal Outlook offers a mixed picture of the UK’s economic outlook and fiscal challenges. On the surface, the numbers suggest stabilisation: growth has been revised up, fiscal headroom has doubled, and inflation is expected to ease back toward target. That should result in lower interest rates and a calmer and more stable economic environment. Yet beneath these improvements lie unresolved structural challenges – high public debt, sticky inflation, anaemic growth, a housing crisis, and a record tax burden – that cast a long shadow over the UK’s economic prospects in the years ahead. Alongside that is the more febrile geopolitical outlook – not raised in the Budget – even as the UK navigates it. If any of these geopolitical challenges materialise, the UK’s forecasts will be blown off course.

For financial markets and corporates, the message should be to prepare for volatility, adapt to higher taxes, and plan for a future in which fiscal sustainability becomes an even tighter constraint on government policy – almost the opposite of the Budget’s message.

Finally, it must be said that this was not a Budget designed to accelerate fiscal economic growth. Rather, it was aimed at redistributing the pie in what the government regards as a fairer way. That approach necessarily had to make the debt ratio more stable to succeed, with several of the tax rises explicitly targeted at achieving just that (see appendix). Yet the trade‑off was clear: higher taxes alongside increased spending. Perhaps a growth‑focused Budget will come another day – but it was not this day. (See appendix 2 for more on what was not in the Budget.)

Economic forecast: modest growth, persistent inflation

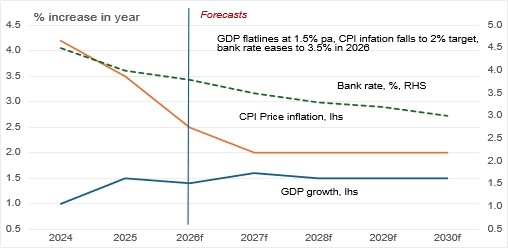

The OBR has upgraded its forecast for annual UK GDP growth in 2025 to 1.5%, up from 1.0% in March. But economic growth is expected to slow slightly to 1.4% in 2026, before stabilising at around 1.5% in subsequent years. While this represents an improvement on the earlier projection, it remains modest by historical standards and below the levels needed to significantly raise living standards and return to the consistent 2% rates seen before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) as long ago as 2008/9.

Consumer price inflation is projected at a 3.5% annual rate in 2025, easing to 2.5% in 2026, and returning to the Bank of England’s 2% target by 2027, see chart 1. This trajectory suggests that households will continue to face elevated prices for several years, eroding real incomes even as headline inflation falls. But rate cuts should also come, mitigating the pressure on households from squeezed budgets and rising unemployment.

Fiscal forecast: headroom today, gone tomorrow

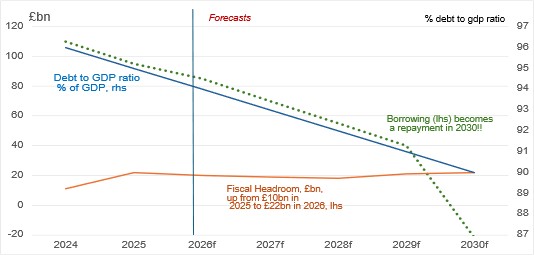

On the fiscal side, the Chancellor has gained breathing space. Fiscal headroom –the margin by which borrowing falls below the government’s self-imposed limits –has doubled to £22bn. The OBR projects a £21.7bn surplus by 2029–30, up from the £9.9bn forecast in March. This improvement is due primarily to stronger near-term growth and higher tax receipts from a ‘smorgasbord’ of measures, see below and appendix.

That at least gives the Chancellor more headroom than she has had so far in her tenure. Moreover, moving to a single annual assessment of the fiscal targets and the budget, as suggested by the IMF, should take the pressure off revisiting them until the next budgetary event due well into the second half of 2026.

Revenue measures play a central role. Freezing personal tax thresholds until 2030–31 is expected to raise £8bn, while broader personal tax changes are expected to raise £14.9bn. These stealth increases underpin the fiscal improvement but also raise the effective tax burden on households.

Borrowing, however, remains elevated. October 2025 showed it at £17.4bn, the third-highest October on record. While the OBR projects a declining deficit, this depends heavily on growth holding up. Any slowdown could quickly erode fiscal credibility.

Public debt: the unresolved issue

The UK’s high public debt and rising refinancing costs pose significant long-term risks to its financial stability, potentially limiting future government spending on infrastructure, health, and education and challenging fiscal sustainability.

Unrealised risks loom large from:

- Demographics: An ageing population will increase pension and healthcare costs.

- External imbalances: The UK’s chronic current account deficit leaves it reliant on foreign borrowing and will likely be made worse by the pension raid.

- Market sensitivity: Bond yields remain volatile, reflecting investor doubts about long-term debt sustainability.

The OBR warns that fiscal credibility hinges on balancing deficit reduction with economic growth, and so a revenue stream to meet the higher debt interest payments is built into the forecast. As the Chancellor said in her Budget speech, public servicing the debt now accounts for one in ten of every pound the government spends.

Without sustained economic growth at least in line with the forecast, the UK’s debt dynamics could deteriorate rapidly. That risk is made even more likely by the febrile geopolitical environment, including in Europe, for which the UK may have to find extra spending.

Financial market view: optimistic but cautious

Markets reacted positively to the OBR’s upgraded growth forecast and fiscal headroom. Sterling rose to $1.32 after the leak, reflecting optimism about near-term prospects. Gilts rallied initially, and the FTSE 100 gained 0.4%.

Yet caution persists. Bond volatility highlights investor unease about the sustainability of long-term debt. Sterling’s gains are fragile, vulnerable to shifts in global risk appetite and domestic political uncertainty. Equity markets face headwinds from higher taxes and weaker consumer demand, even as near-term sentiment improves.

For investors, the outlook is one of short-term relief but long-term fragility. Pension fund inflows may decline due to reforms such as the £2,000 salary sacrifice cap, reducing the pool of patient capital available for equities and infrastructure. That could alter asset allocation patterns and increase reliance on foreign capital.

Corporate and business implications: a challenging environment

For corporates, the outlook is challenging. The combination of modest growth, sticky inflation, and rising taxes squeezes margins and dampens consumer demand.

- Tax environment: Frozen thresholds and NIC changes raise practical tax burdens, reducing household spending power. Businesses face higher compliance costs and potential demands for pay rises to help people cover their expenses.

- Financing costs: Elevated gilt yields translate into higher borrowing costs for firms, particularly those reliant on debt financing.

- Labour market: Rising unemployment signals weaker demand, but wage pressures may persist due to inflation, complicating workforce planning.

- Strategic implications: Firms must adapt to a low-growth, high-tax environment. Productivity gains, diversification, and international expansion become critical strategies.

In essence, businesses face a two-pronged challenge: managing tighter margins at home while seeking growth opportunities abroad. In its publication, the OBR noted that the return on capital will fall due to some Budget changes, putting pressure on corporate finances, and said businesses would seek to recoup those losses. It could be a combination of layoffs, slowing hiring, and pay cuts. For sure, the pressure is on firms to increase productivity.

The structural issue: Britain’s savings gap widens

A deeper structural issue lurks behind the fiscal outlook: the UK does not save enough. Its savings rate lags OECD peers, contributing to a chronic current account deficit and reliance on foreign borrowing. Thus, the £2,000 cap on pension salary sacrifice, while fiscally expedient, risks further reducing savings. The consequence is that the UK’s long-term interest rates and currency become even more dependent on ‘the kindness of strangers’ to fund its current account and budget deficits, further reducing its room for policy manoeuvre.

The tension between equity and efficiency is stark

Equity demands that tax reliefs do not disproportionately benefit the wealthy at the expense of the poor. Efficiency requires strong incentives for all earners to save for retirement. By narrowing reliefs, the government may achieve fairness, but at the cost of efficiency, discouraging higher earners from using pensions and reducing the capital available for long-term investment. See my previous blog for more details.

Conclusion: short-term gain, long-term pain?

The OBR’s November 2025 outlook paints a picture of short-term fiscal relief but long-term fragility. Growth is modest, inflation is persistent, and the tax burden is rising. Fiscal headroom has doubled, but public debt risks remain unresolved. Financial markets welcome the near-term improvement yet remain cautious, while corporates must navigate tighter margins and shifting demand.

Ultimately, Britain faces a two-pronged challenge: stabilising the economy now while addressing structural debt risks that threaten long-term growth prospects. For households and businesses, the implication is clear – prepare for volatility, adapt to higher taxes, and for a future in which fiscal fragility is a shadow over the economic outlook.

Appendix 1: summary table of November 2025 Budget measures

Spending

- Welfare expansion: £11bn by 2029/30, including scrapping the two‑child benefit cap (£3bn).

- Public services uplift: additional funding for NHS, education, and local government.

- Minimum wage increases: fiscal impact indirect (borne by employers, but Treasury assumes knock‑on effects on tax receipts and benefits).

Tax Rises

- Income tax & NI threshold freeze until 2031: stealth tax raising ~£20bn annually by 2030/31.

- Mansion tax on £2m+ properties: several billion annually.

- National Insurance on salary sacrifice pensions above £2,000: smaller but steady revenue stream.

- ISA reform (cash allowance cut): modest but positive revenue impact.

- Other tightening measures: smaller adjustments across reliefs and allowances.

Net outcome:

- Spending increase: ~£11bn by 2029/30.

- Tax rises: ~£26–30bn annually by 2030/31.

- Net fiscal effect: positive consolidation of £15–20bn per year by end of decade, helping meet fiscal rules (balancing day‑to‑day spending with receipts by 2029/30).

- Debt trajectory: OBR projects debt/GDP stabilisation, though still at historically high levels due to weak growth and high interest costs, see charts 1, 2.

Appendix 2: Key structural economic issues the Budget did not address

- No significant measures to boost housing supply or ease landlord pressures.

- Limited new incentives for SMEs beyond wage and tax changes.

- Growth strategy muted, with the OBR downgrading forecasts for 2026 to 1.4%.

Impact of the OBR’s downward growth revisions

- Downgrade: Productivity growth cut from 1.3% → 1.0% over the forecast period to 2030, a 0.3pp reduction.

- GDP impact: 2026 growth revised down from 1.9% → 1.4%, reflecting weaker output per worker.

- Fiscal effect: Lower productivity reduces tax receipts by ~£16bn by 2030, tightening fiscal headroom.

- Structural challenge: The UK remains below its long‑term productivity average and behind peers, limiting fiscal and monetary flexibility.

No significant measures to boost housing supply or ease landlord pressures. In fact, the Budget changes will reduce housing supply.

Why the Downgrades Matters

- Underlying weakness: The OBR stressed that the UK’s productivity performance has consistently undershot forecasts since 2010, with rebounds from shocks failing to materialise.

- Fiscal impact: Lower productivity means slower growth in wages and output, reducing tax revenues by £16bn to 2030, lowering the fiscal headroom.

The risk is that, after a few years, the headroom falls so far that taxes have to be raised again to buttress it.