This is the first Labour Budget since 2010, and the first by a woman in UK history. It is aimed at raising economic growth in the long run, funded by tax rises and increased borrowing in the short term. The tax rises mainly came from employers’ National Insurance contributions and employers’ contributions to pensions, which account for £25 billion of the £40bn increase. It’s the biggest tax increase since 1993.

However, it’s crucial to note that this is a tax on employers, and they are likely to pass much of it on to employees. This could potentially lead to lower pay increases or a reduction in the level of employment compared with what would have otherwise been the case. The potential effects on the UK’s overall wage structure and employment levels are significant and need to be carefully considered.

Unexpected spending

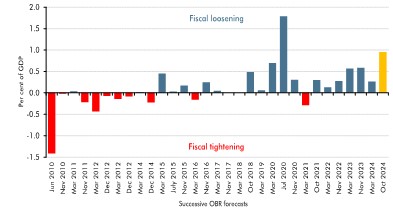

While the main themes of the Budget were not surprising, some of the specific details were unexpected. For instance, the £40 billion tax increase was larger than anticipated, as indicated by the spike in 10-year gilt yields immediately after the Chancellor’s speech. Over the parliament’s term, public sector borrowing will be £140 billion higher than it would have been otherwise. Government department spending is planned to rise by 4.3% in 2024/25 and 2.6% in 2025/26 but then slow dramatically to just 1.3% in 2026/7 and 2028/8 and 2028/9. This dramatic slowdown in funding could have a significant impact on the affected departments. Will they be able to function effectively with such a reduced budget, or will they push back for more money as cuts in inflation adjusted spending may loom?

Another question about the sharp increase in department spending in the first two years must be whether they can spend so much money so quickly and yet does so efficiently and productively? Despite these caveats, it’s important to note that the International Monetary Fund, a respected authority in fiscal matters, has deemed the spending proposals necessary and has lent its support.

Large tax rise and increased borrowing

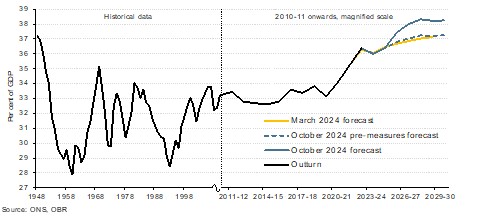

The tax rises were significant enough to prevent public spending from decreasing in real terms and, most importantly, to avoid a return to austerity and cuts. Hence, taxes will rise to a post-war high.

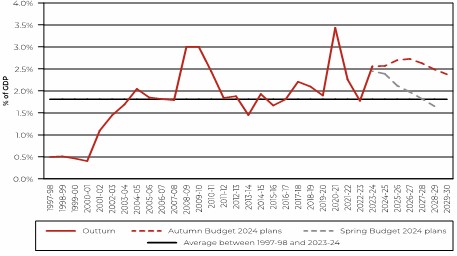

Under the previous Government’s spending plans, actual department spending was set to fall in real terms. However, these tax increases and higher borrowing effectively averted that outcome. Public sector investment spending was boosted to prevent it from further declining this year as a share of GDP, a trend of rising and falling that has persisted since 2010, as shown in Chart 3.

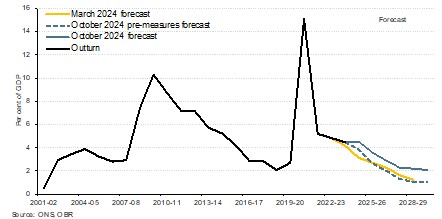

The tax increase and additional borrowing were crucial to prevent further cuts in public services and other government investment spending, thereby avoiding the effects of another damaging austerity. However, public sector net borrowing will align with the previous Budget over the next five years, as shown in chart 4. In other words, there is no irresponsible loosening of fiscal policy over the medium term. Moreover, the government meets its two new fiscal rules, that current or day-to-day government spending is met entirely from tax receipts and that net public sector financial liabilities are falling as a share of GDP over a three-year period, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

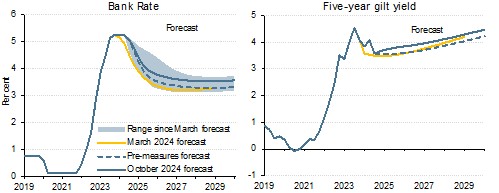

However, it may imply higher interest rates as the loosening was more than expected, and the economy may grow more strongly than the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) thought before the Budget. According to the OBR, interest rates may be ¼ of a percentage point higher than they would otherwise be. However, that does not mean that interest rate cuts are unnecessary since inflation of 1.7% in the year to October is proof that the inflation target is being met at a time when economic growth is anaemic.

That said, the Budget’s short-term boost to growth may well mean that interest rates do not fall as rapidly and as much as they did before, see chart 5. However, the medium-term trend for UK inflation is downward. Although it may temporarily rise, it will fall back to the 2% target in early 2025, well within the medium-term horizon that the MPC is meant to take account of. So, regarding expectations of a rate cut at the November 7 MPC meeting, it may mean a ¼% reduction rather than one of half of a per cent.

However, my view is that unlike the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve, the MPC has been cautious in its approach to rate cuts, so there is scope for significant cuts despite the potential effects of this Budget.

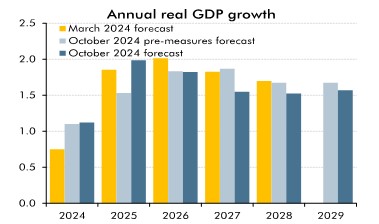

Although UK economic growth is faster in 2025 and 2026 in the final two years of the forecast period, it falls below the rates shown in the March budget by the previous administration. In other words, over the entire forecast, the level of GDP is not much higher than it would otherwise have been, see chart 6.

Part of the reason is that although there is a boost to productivity in the near term, it begins to weaken towards the end of the five-year forecast. It may be the case that the investment regime changes – including policies and regulations that govern investment activities – will take longer than five years to boost productivity. Still, they will have a significant impact in the short term. A fiscal injection always boosts an economy in the short term. However, whether it increases economic activity in the long term is much more difficult to judge and history suggest a lack of a permanent impact without accompanying structural reforms.

Other policies announced

On the specifics that were widely floated beforehand but didn’t occur: there was no increase in fuel duty, income tax thresholds were frozen until 2028/29 and will then increase in line with inflation, and there was little mention of business rates, but a consultation will take place, meaning any change will take at least a couple of years. Farmers will be charged Inheritance tax for the first time. However, if the farm is gifted 7 years before the owner’s death, then the tax won’t apply.

Conclusion

While much was expected from this Budget, it’s important to remember that the private sector necessarily dominates the long-term trajectory of an economy. The pace of long-term economic activity in an economy is based more on the growth and quality of the country’s labour force, the size and quality of investment in the capital stock, its trading relationship with the rest of the world, and so on. For example, the mooted changes to the UK’s planning regime, which could unlock further potential growth, are also significant for promoting a new climate for accelerating investment in key sectors by the private sector.