What do Russian oligarchs, the selling of UK companies to foreign investors and the slide in the pound all have in common? The answer is they all help to fund the UK’s growing current account deficit. And it is indeed widening. In Q1 2022, the UK’s trade deficit was £33.4bn, and the current account deficit was £51.7bn. In the whole of 2021, the UK trade deficit was £29bn, and its current account deficit was £60bn

How does this work? The answer is that the oligarchs and others, by buying property and football clubs, pumping money into the UK, have been effectively lending it money. More generally, key UK corporate brands are being bought by overseas investors, also helping to finance the trade deficit. But the number of UK firms with market capitalisations of $250bn or more is few and far between. With the oligarchs ostracised and fewer large companies to sell, the deficit will swell, and the pound will fall further.

Its fall will lead to upward pressure on imported inflation, as goods bought abroad cost more in sterling terms, and this is one reason why the UK’s inflation rate is one of the highest of the G7 economies. All this begs the question, how sustainable is the widening UK current account deficit if it leads to these outcomes?

Balancing the country’s books

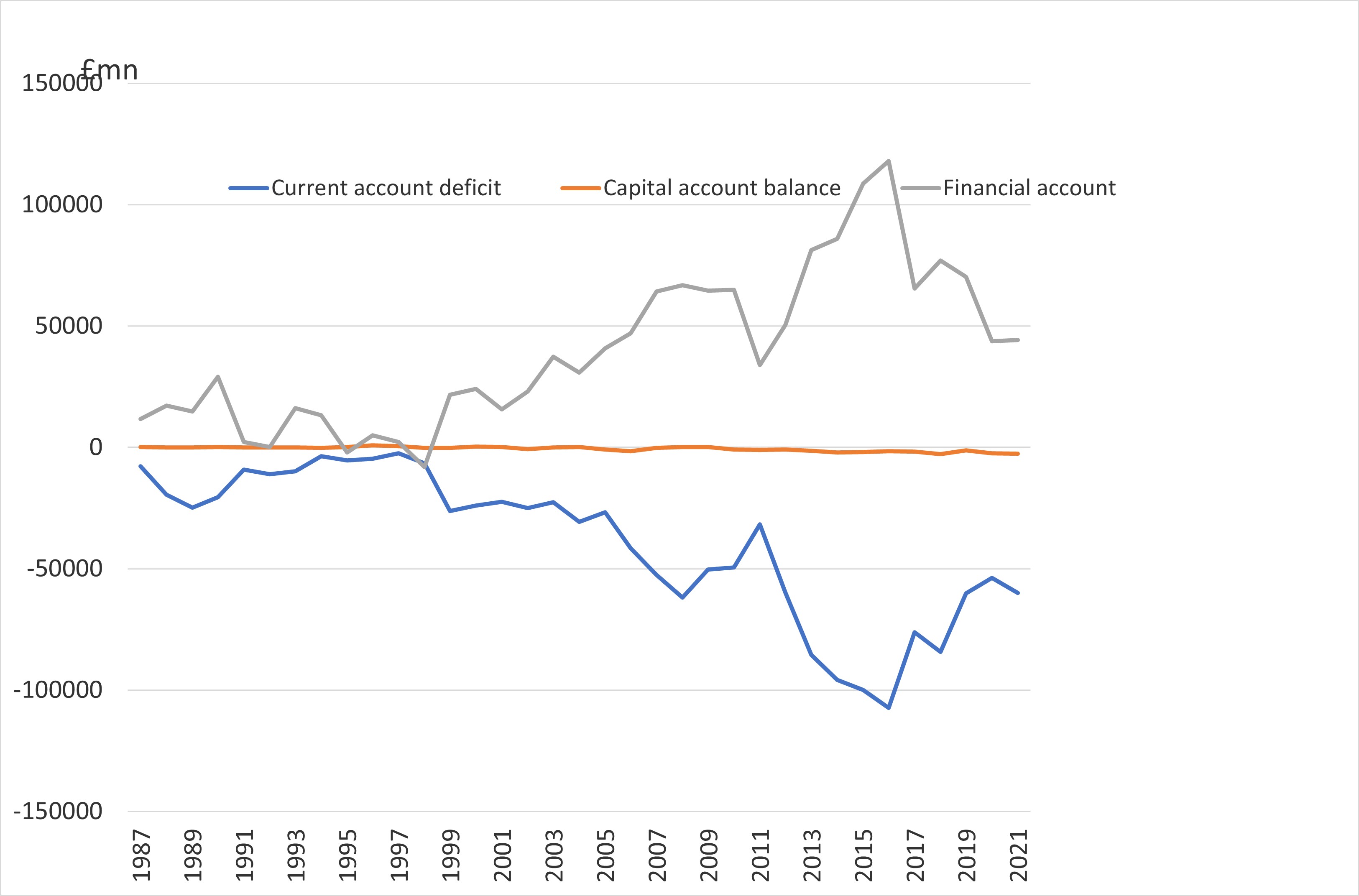

A country’s balance of payments consists of three main categories: a current account, a capital account, and a financial account. Each of them measures activity between UK residents and non-residents.

The current account comprises a trade account, a services account, and an income account. The UK used to have an account surplus because services exports net of imports was sufficient to offset deficits on the trading account and income accounts. But this is no longer the case, or at least not since 1984.

The capital account has two categories: capital transfers and purchasing or selling non-produced, non-financial assets. It used to run a surplus, but now it no longer does so. However, the current capital account’s imbalance is still relatively small and is not at the core of the UK’s trade imbalance.

That leaves the financial account, which covers transactions between residents and non-residents that result in a change of ownership of financial assets. These include acquisition or disposal (a net position) of foreign shares by UK residents, direct investments in and out of the UK, portfolio investments and other types of financial derivatives and asset shifts. The financial account must, therefore, run a sufficient surplus to offset the deficits on current and capital accounts.

In summary, the UK’s total inflows must match its total outflows. It’s not rocket science, and that task now falls to the financial account; see chart 1.

Economic consequences

The good news is that countries can live beyond their means by borrowing, just like individuals. The bad news is that, just as for individuals, there are limits. Funding a current account deficit is, therefore, not a trivial matter. As history has shown for several countries, including the UK, perceptions of difficulties in funding these deficits can lead to substantial capital outflows and currency crises, which can have severe negative domestic economic consequences.

The current account deficit reflects that the UK is living beyond its means, and it has been borrowing from abroad to bridge the difference between what it is spending and earning.

A persistent current account deficit means the increasing sale of domestic assets such as companies, equities, bonds, or property to fund it. To make these assets more attractive to foreign investors, they must also become cheaper in foreign currency terms.

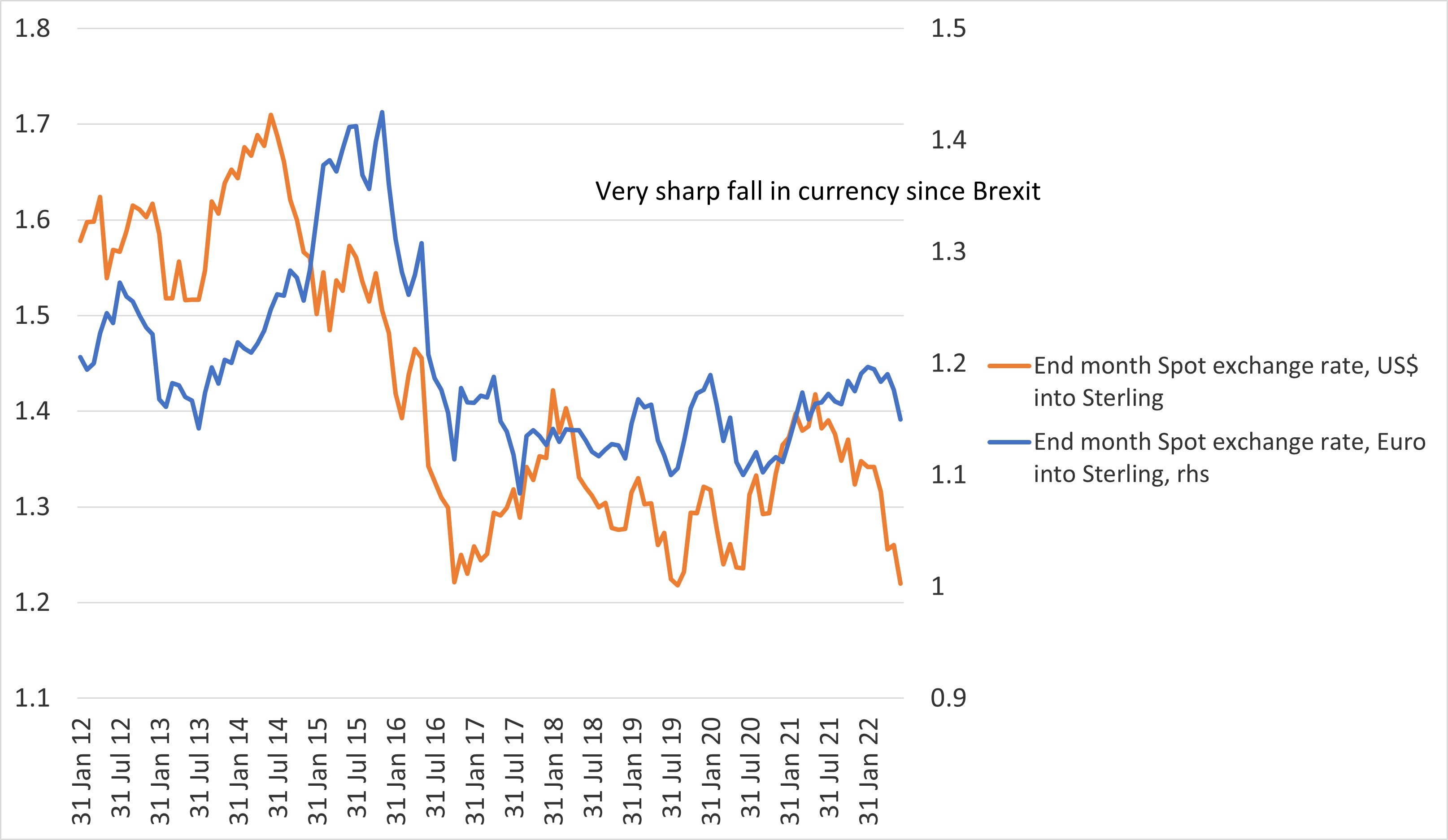

Charts two and three show that the UK’s currency has fallen sharply against its major trading partners – the EU and the US – though less so against all its trading partners on average.

The drop against the currency of the UK’s biggest trading partner, the Euro area (over 40% of trade), has been 20%. The pound’s fall against the US$ was close to 30%.

The Brexit-effect

A complicating factor, of course, is Brexit, with the referendum in 2016 leading to a sharp fall in the currency from which it has never really recovered.

As long ago as March 12, 2017, the Bank of England said this of the increasing inflow of capital required to fund the UK’s widening current account deficit:

“Over recent quarters (the current account) deficit has been increasingly funded by capital inflows – rather than sales of foreign assets by UK residents – thus increasing the UK’s reliance on the confidence of foreign investors”.

What does this mean? Usually, an inflow of capital from abroad is seen as a good thing for an economy. But it’s crucial that it’s investment purposes, which drives up productivity and future income to pay for the borrowed money. However, if it’s simply to allow a country to consume beyond its means; the current account deficit will get bigger and bigger until it reaches a point where it’s no longer financeable.

Finding a workable alternative

What are the options? The deficit can be reduced if the UK consumes less from overseas. Another solution is to produce more at home. But is boosting manufacturing still possible, or is that now too tall an order in a world where competitors like China loom so large? Or export more financial, management, accountancy, gaming, and legal services. But that might mean trade deals that open markets to UK services exports.

Alternatively, it can continue the same course it has been on for the last few decades, selling more of its companies and properties to overseas investors – from wherever it can find them – and welcoming inward investment. However, as Brexit suggests, this may no longer be a realistic long-term strategy. The challenge is to find a workable alternative.

Without the latter, there could be rolling sterling crises, and interest rates might have to be raised sharply, provoking a recession. That could be the only way of squeezing inflation out of the economy and, simultaneously, reducing the size of the current account deficit. A lower deficit eases the depreciation of the pound, which of course, contributed to the rise in consumer price inflation in the first instance. But such an outcome will also leave the UK and its citizens poorer. By far the best solution is for productivity to increase but achieving that is not an easy task as the failure of efforts to do so over the decade since 2007/8 have shown.