There’s so much wrong with the recent trade agreement between the US and the UK that it’s difficult to know where to start. First, it’s not a trade deal as it does not reduce tariffs or set the terms for trade between the two countries; instead, it is an agreement about a potential deal. But it is not enforceable, and little of it is written down.

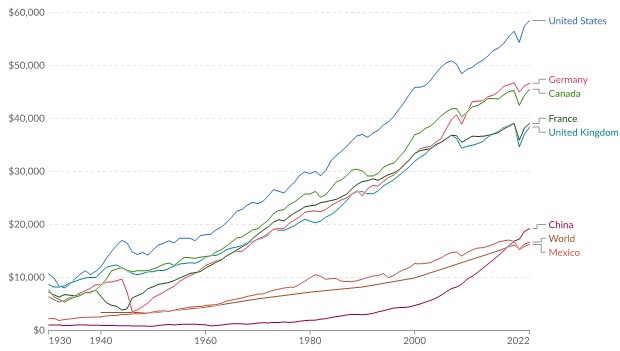

Most of it is vague and refers to the need for further debate, discussions, and agreement. Secondly, by applying these terms unilaterally, the US government has reneged on its international obligations, and it would not be surprising if World Trade Organization (WTO) members were to file dispute settlement cases against it. They are likely to succeed. This would perhaps facilitate the complete withdrawal of the US from the WTO. That would, of course, be very damaging to the global trading system and the US, which has been one of the main recipients of the benefits of free trade, as we see in chart a.

As Adam Smith pointed out in his 1776 book:

“After the division of labour has once thoroughly taken place, it is but a very small part of these [necessaries, conveniencies, and amusements] with which a man’s own labour can supply him. The far greater part of them he must derive from the labour of other people.”

There are a few other points worth making that show why multilateral deals are better than bilateral deals. Powerful countries – or, more precisely, those individuals and companies most connected to the government – like bilateral deals because they can get more of what they want, usually for themselves and their friends, not the ‘country’, which as they see it, is them. Deals like these are typically tied to individuals, or firms owned by individuals directly or indirectly involved in the deal, or friends and family of those making the key decisions. It is called crony capitalism.

This isn’t rocket science. It has been known for centuries. That is why a rules-based trade system was developed after the end of the Second World War, with many of those rules put in place at the behest of the US. It is of course, the WTO and it was created to hold the powerful to account by setting rules that everyone had to follow. Those that don’t follow the rules, that they signed up to, and which were written into treaties, would face enforcement in law – in theory at least.

Clearly some countries would like to get rid of is any enforcement mechanism. In the US/UK Agreement, it’s no surprise that there is no enforcement mechanism. It is purely subject to the whims of the strongest of the two, which in this case is, of course, the US.

Moreover, the inefficiency of this process cannot be overstated compared with letting ‘an invisible hand’ make the decisions.

If the US does decide to go it alone, it would have to strike nearly 200 deals with other countries worldwide, which raises the question of whether that is the best use of government time to monitor each deal, enforce it, etc., mechanisms that are already in place as part of the WTO.

The capriciousness of deals like this is demonstrated by the incumbent in the White House tearing up the trade deal he struck between the US, Canada, and Mexico in 2017 and rewriting it in a way that currently suits the US as if the previous Agreement never happened.

Trade deals like these lead to nepotism, corruption, and crony capitalism, for power has been given to those with incumbents involved in the deals. This is not about economic efficiency; it is not about raising productivity or wealth creation but state graft, which will leave the economy worse off. Business depends upon the rule of law, contract enforcement, an unbiased legal system, and a process through which objective and rational decisions can be made based on trust and belief that the system will deliver and operate fairly for all concerned.

That would produce greater investment, through turning savings into products made by firms that meet people’s wants and needs and give them an income to live on as well.

Why the UK deal is unlikely to survive contact with reality

Despite the UK PM’s statement suggesting zero tariffs on steel and aluminium exports to the US, the lack of explicit mention of zero tariffs casts serious doubts on that assertion. This ambiguity has left pharmaceutical firms in the dark about what future tariffs may mean for their sector, highlighting the need for more transparency in trade agreements.

There was no mention of aerospace or parts in the text. Unanswered questions: the deal is replete with them. It all seems more of a PR stunt than anything serious. There is no legal structure around it, not even a signed document. One wit noted that the pact is closer to protection money being paid to a mob boss to do business in the area he controls than a trade deal between two sovereign countries.

However, given that it is willing to concede so much, it has profound implications and consequences for future UK and perhaps current trade deals. It helps to put at risk the global trade system from which the UK has benefited so much. It is also illegal in that the UK struck a deal that is not multilateral and is outside the scope of the agreements it has already made with other WTO countries.

It’s called ‘the most favoured nation principle’, which is that a deal for one is the same for the others. Seeking special access within that umbrella with other countries is ruled out, meaning other WTO member states could object to the UK’s carve out deal with the US.

Trampling on the rules-based trade order

It’s worth noting that the UK, a staunch supporter of free trade and a multilateral rules-based system, has taken a different approach. It has seemingly capitulated to the US and, in a rush for a ‘deal’, has encouraged others to do the same. This shift in stance could undermine recent deals like the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) or efforts to join Mercosur, the South American trading group.

Undermining a rules-based trading system designed to prevent future wars by encouraging countries to get wealthy by trading with each other does not help anyone. While it has not led to the end of all wars since 1945, it helped prevent some of them from breaking out and reduced their intensity. However, undermining it risks an escalation just as it seems to be returning to a pre-World War 2 period where ‘might is right’.

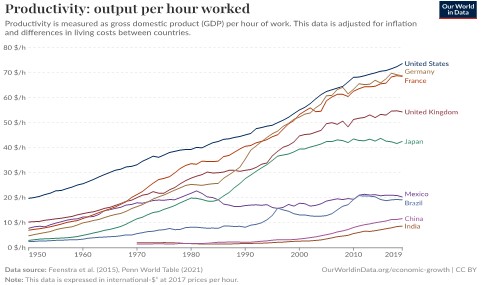

The incumbent in the White House is rapidly undoing 80 years of work to build up a network of trust and world institutions that has led to an unparalleled increase in global wealth and prosperity. By now, this should be clear to everyone. The consequences are greater uncertainty and a significant loss of potential wealth and prosperity for everyone, including the US, especially considering how well it has done since the 1950s, see charts.

The widespread evidence of increased willingness to ignore rules and smash grab exists worldwide. Sadly, it looks like it will get worse before it gets better. The US decision to raise tariffs on all its trading partners, friends and foes alike, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the ongoing wars in the Middle East and Africa are a sign of the end of the 20th-century consensus. What will replace it is still uncertain, which should be a cause for immediate concern. The situation seems eerily reminiscent of the interwar period of ‘Great Powers’ and ‘spheres of influence’. One hopes for better outcomes this time, as that period did not end well for the world, but planning for the worst might also be smart.