As was widely expected, the new Prime Minister, Liz Truss, has opted for an energy price freeze. It caps the price for the typical energy consumer at £2500 for a unit of energy for two years. But this still represents a sharp increase compared to the previous price cap and the year before. Roughly speaking, it’s double the price of a year earlier and is 56% higher than the April 2022 price cap. But it would have been a 98% rise without the price freeze. It also avoids what may have been an increase to £5000 in January 2023 as the price cap process was recently switched from quarterly to monthly assessments.

Moreover, the government’s price freeze includes small businesses – unlike the furlough scheme – though limited to six months and starting later for administrative reasons involved in identifying qualifying firms.

Counting the cost

But it comes at a cost to taxpayers of around £150 billion, depending on how wholesale gas prices behave over the two years (compared with £80bn spent on the furlough scheme though it did not include small businesses).

It could be well above that figure, depending on the difference between the cap and the wholesale price that the government is committed to not passing on to consumers. Therefore, the government is exposed to the risk of an unquantifiable liability because of the price guarantee.

Implicitly the government has taken a position on a fixed price relative to a market price and faces a margin call whenever they diverge – without any get-out clause or explicit limit on the upside exposure. This uncovered position is sometimes called a ‘naked short’ in market jargon. Effectively, the authorities have said that, if the market price were to rise above the cap of £2500, they would not charge consumers a percentage or ratio of the increase or indeed cap their risk.

Into the unknown?

On the one hand, the good news is that there are signs that the wholesale price of gas appears to be coming off the high it reached before the cap was put in place. On the other hand, the winter has not yet started, and who knows how the war in Ukraine will proceed? We will not know the total cost of the price freeze until the scheme ends.

Moreover, unlike the EU, which has placed a windfall tax on energy firms of €140 billion, the incoming administration of Liz Truss has ruled out any windfall tax, which means the total cost of this rescue will be borne entirely by future taxpayers.

Admittedly, this may be because it might have taken time and been rather messy to implement; nevertheless, it’s in stark contrast to what other European countries are doing.

Understanding the links

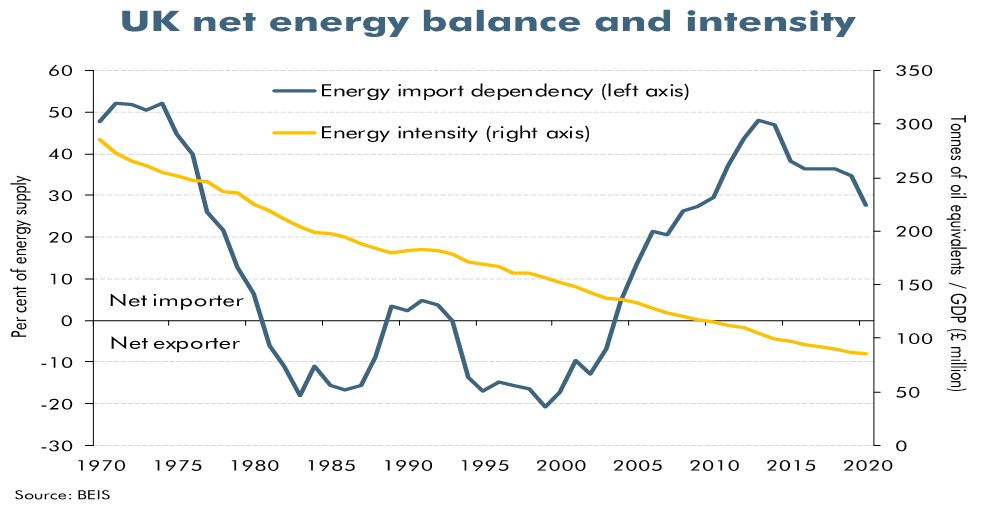

At this point, it may be worth pointing out that the link between gas and electricity costs in the UK is purely a function of how the UK prices its energy supplied to consumers. The UK produces roughly half of the gas it consumes and almost all its electricity. Indeed, recent figures show that the UK sometimes exports electricity to other countries that it’s linked to via an underwater grid.

But the pricing structure for providing energy to consumers in the UK has been configured so that the price of gas and electricity are linked, which means that any marginal pricing for gas also impacts the cost of electricity. Delinking the two would go some way towards reducing the energy price facing UK consumers, but at this moment, there’s little chance of this happening. Essentially, there is a redistribution from energy-consuming households and industry to electricity suppliers and gas producers.

Although the world produces more than enough gas for its needs, Europe has been dependent on Russian gas and, therefore, with that being withheld, is facing a shortage. But subsiding energy prices by underpricing it relative to the market price and it’s supply, simply runs the risk of underpinning demand and could result in chronic shortages, blackouts, and rationing.

In other words, given that help is required and necessary this winter, some level of European-wide cooperation on support measures is needed.

Realpolitik

Of course, this is taxpayer exposure and means that those benefiting from the price cap will eventually have to pay for it.

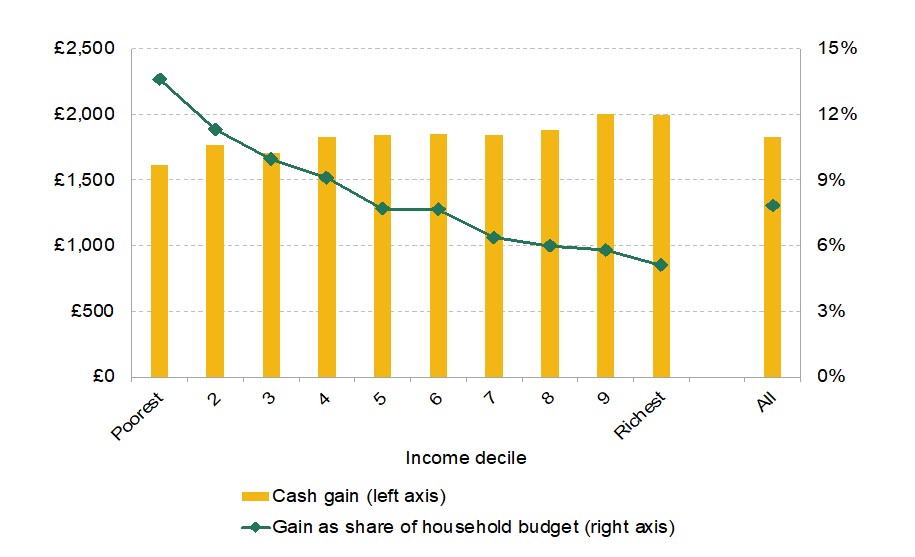

This reflects one of the points that the Institute for Fiscal Studies has made about the cap, which is that it will support some that can afford to pay for it, yet all taxpayers will have to contribute, even those who need the price help the least. As shown in chart 2, it is accurate that in cash terms, those on higher incomes gain the most and need the least support. Yet, the chart also shows that, as a percentage of income, those who have received the most help are the ones with the lowest income.

But still, it could have been done in another way, just as during the pandemic. Why not just directly give money to businesses and to those who require help with energy? For example, increasing universal benefits to those that receive it. You could give each household on means-tested benefits £3500 or £6000, and £2500 to everyone else, or not give anything to anyone else as they are not on means-tested benefits. For business, the support could be open to those applying for the scheme, and so long as you are registered as a small business, you will be eligible for it with the necessary checks.

Perhaps this list is the reason for not going down this route; it’s simply too complicated and would take too long, and therefore it’s just not a practical or sensible short-term solution. Or perhaps there’s another explanation.

Although this is ‘big’ government rather than ‘small’ government, it’s more Keynesian than Milton Friedman; it is more politically Labour than Conservative, but that’s politics for you!!