Let’s begin with a few quotes from Adam Smith to set the context for the following discussion about why free trade matters:

“After the division of labour has once thoroughly taken place, it is but a very small part of these [necessaries, conveniencies, and amusements] with which a man’s own labour can supply him. The far greater part of them he must derive from the labour of other people.”

At its core, the concept of free markets is the ability to produce goods and services freely, both within a country and without. This process leads to specialisation, the division of labour, economies of scale, and, therefore, rising productivity, which we can describe as a rise in living standards. These benefits underscore the importance and value of free markets in delivering wealth, but that we are also dependent on the efforts of other humans to derive that benefit.

That means no product is made entirely in one place or location, instead the production process is determined by efficiency and cost-effectiveness. No outside agency should interfere in that process. It should be as if these were being directed by ‘an invisible hand’.

To quote Smith he thought it better to leave it to individuals or markets.

“Every individual… neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it… he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.”

As Adam Smith also pointed out:

“The tailor does not attempt to make his own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker. The shoemaker does not attempt to make his own clothes, but employs a tailor.”

And he goes on to say:

“If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.”

In an earlier publication, the Theory of Moral sentiments, Smith referred to leaders and politicians thus, as he was very skeptical not only of their ability to deliver but the reason for the actions being taken:

“The man of system, … very wise in his own conceit,… [who] seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board.”

Of course, the argument could be made that the democratic process means that elected politicians are mandated to carry out the wishes of their electors. That would not be easy to argue with, except as Peter Warburton points out in Economic Perspectives, the mandate may not be as significant as it appears. In June 2016, for example, 37.4% of eligible voters (7.1 million out of 46.5 million) voted in a referendum to take the UK out of the EU. In November 2024, 31.8% of eligible US voters (77.2 million out of 242.6 million) voted for a president whose avowed intent was to impose tariffs on its trading partners.

Moreover, Adam Smith said that politicians may not necessarily deliver success in trade matters as they

“are directed by the momentary fluctuations of affairs”.

And even when trade issues may need addressing, making purely political decisions is not a good way of reaching the best outcome as he doubts their ability to succeed:

“When there is no probability that any such repeal can be procured, it seems a bad method of compensating the injury done to certain classes of our people, to do another injury ourselves, not only to those classes, but to almost all the other classes of them.”

He goes on to say:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our necessities but of their advantages.”

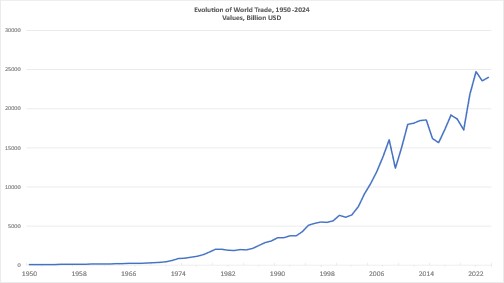

The beauty of the global trading system is its efficiency and appeal to self-improvement. Over 75 years, especially driven by technical innovations in transportation and refrigeration, it has created an intricate global-spanning supply chain and networks of suppliers and producers across as many as 150 countries.

It operates like a living organism, adjusting, flexing, and finding new pathways as and when new supply comes on board, new countries join, or when fads change, technology changes and roots shift. It impressively finds the optimal way of delivering products that people worldwide want at the right time at the best possible price. Technological advances make this easier, making it possible to produce things ‘just in time’ and track and deliver multiple products to individual people around the world who are in the ecosystem.

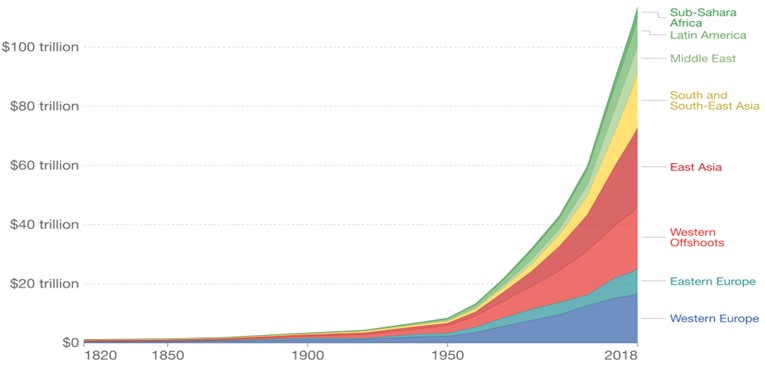

What about the actual evidence on trade? The chart below shows that the greatest increase in global living standards in the history of mankind has taken place in the last 200 years. The whole world is now involved in a global trading system, which has as its core the aim of improving wealth and raising living standards.

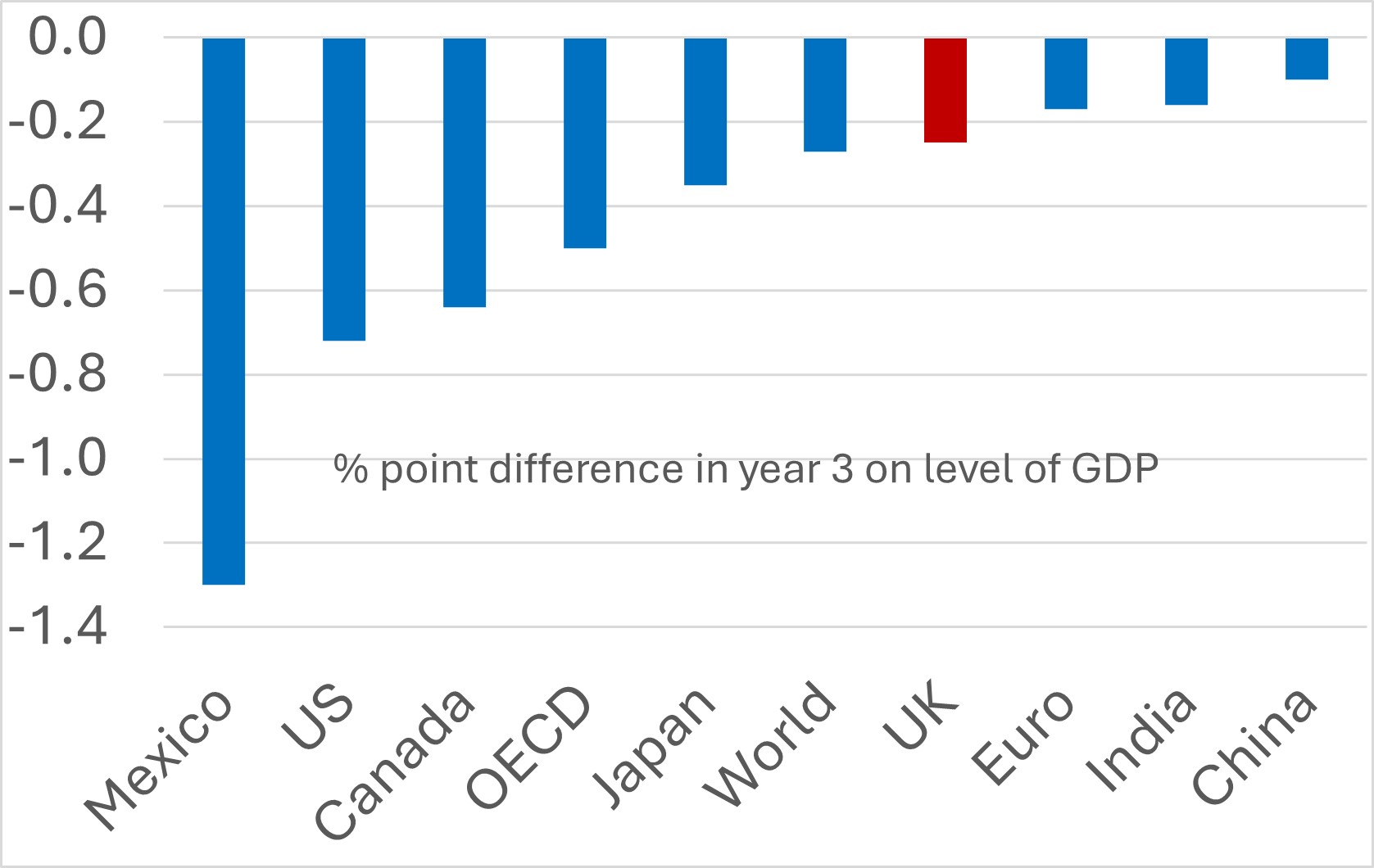

If one looks at the OECD calculation of who loses the most from the trade deals that the US has imposed tariffs, it is the US itself, almost as much as Mexico’s 1% loss in GDP, see chart below.

One ray of good news is that the US consumer accounts for 12% of global imports, meaning that 88% of global import trade accords between other countries in a part of the WTO. And they have not imposed additional tariffs on each other. That means there will be no ‘beggar thy neighbor’ policies as there was in the 1930s, and which contributed to the Great Depression. However, recent announcements from Trump of new tariffs on the EU and even US firms’ products made abroad are clear signs that this issue is not going away anytime soon.

Finally, let’s consider for a moment the moral case of imposing 49% tariffs on Cambodia or 46% tariffs on Vietnam, both countries where US and Chinese firms make goods before shipping them to the US.

The US benefits greatly from the low-value products, such as clothing, shoes, and trainers, which they produce. If they now become high-priced in the US, it imposes higher process costs on poor Americans and causes enormous economic damage to these relatively poor countries. The latter, which were also heavily bombed by the US in the Vietnam War, and to which one could argue it owes some moral obligation to help, has been hit with Tariffs as much as any other.

Smith asks or hopes for more generosity of spirit in Moral Sentiments, 1749, writing:

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune o others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

A recent study by Johan Norberg, ‘Peak Human’, on the success of empires and countries over the ages shows that openness and freedom of movement of people and goods form the basis of successful periods. Golden ages fail when they turn inward and shut off the outside world of ideas, people and goods.

We are either at or approaching a pivotal moment, a critical juncture in global economic history. However, although some countries that have started the industrialisation process in Europe and the Americas seem willing to jettison openness and turn inward, the rest of the world doesn’t seem willing to let go of it just yet. It is also a moral and economic benefit to everyone that war and strife are constrained by increasing wealth and prosperity. We should not grudge that of our fellow humanity.