One in 100-year events are supposed to be rare, but we have had two within the last ten years. The first was the global financial crisis in 2008 / 2009. The second is now the global pandemic. It means they are happening with more frequency, and as a result, we should be expecting another one within the next decade or so. The reason for the rising frequency of this type of event is increasing globalisation.

It is not just that the world is more connected by the Internet or by the communications revolution as well as by the increasing number of people travelling more frequently than ever before, but there are also more linkages. Events taking place in one part of the world causing reactions in other parts of the world.

This is evidenced by the fact that the lockdown, which is occurring around the world, now involves countries which account for more than 90% of global GDP. Some 170 countries will experience some form of contraction this year. The result is that the impact on global growth will be more significant than in previous downturns; of course, we have to be clear this is a deliberate act of policy. The lockdown is meant to save lives. In saving lives, it saves the economy.

So, there is no trade-off between saving lives and saving the economy (see my previous blog). In that sense, the economic downturn that the world is experiencing cannot be compared to previous economic downturns. This is not the result of an excessive economic expansion creating inflation bubbles in the economy, which had to be counteracted by a classic tightening of fiscal and monetary policy.

Whilst the damage in terms of loss of income, increases in unemployment, falls in output, and company liquidations is still the same, government actions have been swift. Increased public spending and sharp cuts in interest rates and a general loosening of monetary policy have occurred.

A global impact

To give a sense of the hit to the global economy from the virus: China has just announced a 6.8% drop in its first-quarter GDP growth in 2020, the first decline in quarterly GDP since 1976. However, China has not announced a meaningful loosening of fiscal or monetary policy. Partly as a result of this lack of policy action from the second-largest economy in the world after the US, global GDP growth is expected to decline by 3% this year according to International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts. However, China’s economy is already showing signs of recovery and, with business activity resuming, growth is expected to pick up quite rapidly in the second, third and fourth quarters of this year.

Pretty much the same pattern is expected in other economies around the world, with a majority experiencing a one-quarter drop in GDP in Q2 2020. The assumed path of economic recovery in the world is that output picks up through the rest of 2020, followed by a continuation of growth in 2021.

Thus, IMF forecasts – and that of the consensus – show global GDP at around 4% in 2021 after the 3% drop this year, making up for the plunge this year in percentage terms. But not, of course, in terms of the level of GDP, or where the economy would have been if the crisis had not occurred. It is likely that that loss of output will never be recovered. And all of this, of course, assumes that the exit strategy works. That is to say that there is not a second wave of infections that causes a second lockdown and so further damage to the economy.

What is an exit strategy?

Firstly, it consists of a gradual return to work of critical workers in crucial sectors, keeping social distance in place as much as possible in the workplace. Secondly, the ability to do the latter could influence which firms open, in which sectors and in what order. Thirdly, the need to ensure that the pandemic does not return by a close examination of the epidemiological data. That is to say, that the infection rate of each person is less than one. That, in turn, will depend on the fourth criteria, testing, follow up, tracing and rapid isolation of those infected so that the virus does not spread anew. In the end, only a vaccine and ‘herd immunity’ can prevent further outbreaks but in the interim these measures ease the lockdown.

What about the UK?

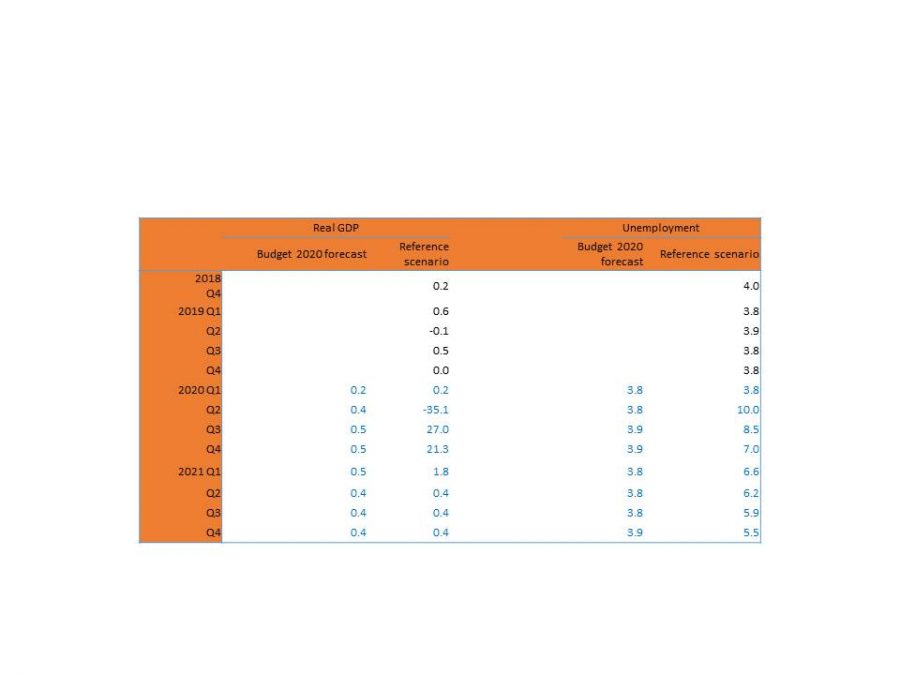

The path of the UK’s recovery pretty much mirrors that which the IMF has projected for other economies. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has just released their latest update for UK economic and fiscal projections for the next few years. It makes grim reading on the impact of the pandemic on the UK economy. Table 1 shows the effect of output losses by sector in the UK in the second quarter of this year. It depicts a total decline of 35% in GDP in Q2, and which industry sectors have contributed the most to that decline.

Table 1: UK Output losses by sector in the second quarter of 2020

Not surprisingly, with the impact of the shutdown on education, its effect on output relative to the baseline in that sector is the largest, at nearly 90% less activity compared to where the level would have been in the absence of the lockdown. This accounts for 5.2 percentage points of the 35% drop when its share of total output is taken into account. For the accommodation and food services sector, output is down 85% relative to its baseline but accounts for just 2.8 percentage points of the GDP fall.

In the construction sector, which is 6.1% of the economy, output is down 70% relative to its benchmark and contributes 4.3 percentage points to the decline in total GDP. For manufacturing – 10.2% of the economy – output is down 55% relative to its baseline, taking 5.6 percentage points off growth in Q2.

It is worth noting also that real estate output is down 20% compared to its baseline, taking 2.8 percentage points off GDP when its 14% share of the economy is accounted for. The fortunes of this sector are, of course, closely linked to the construction sector, which implies that the hit to the housing sector in the UK has been immense (7.1% off GDP). One area of huge debate after this crisis is over will be what happens to those at the lower end of the housing ladder? Many of those that are now known as ‘essential workers’ fall into that category.

The one sector showing a definite increase compared to its baseline is, of course, the health and social services sector, which has borne the brunt of ensuring that the virus does not take an even more enormous toll on human life, with output up by 50%.

Table 1 shows the toll on the overall economy. The quarterly fall in output that the pandemic is expected have on the UK is a 35% drop in Q2 – following a modest 0.2% rise in Q1 – then a 27% recovery in Q3 and 21% in Q4. This means that overall UK GDP drops by 12.8% in 2020 on average, but the Office for Budget responsibility (OBR) is expecting GDP to rise in 2021 by 17.9%, effectively making up for the losses which occurred in the previous year.

The hit to unemployment, however, is not so quickly reversed, as shown in Table 2. The unemployment rate climbs to 10% from 3.8% the year before and then averages around 6% in 2021, meaning that the full effects of the crisis are not unwound even a year later. One clear implication from this is that business bankruptcies etc. persist so that the level of employment is around a million less than pre-crisis. But without the government’s action to pay 80% of employees temporarily laid off (furloughed) and help for the self-employed, then the hit to employment would have been far more significant.

The long-term impact

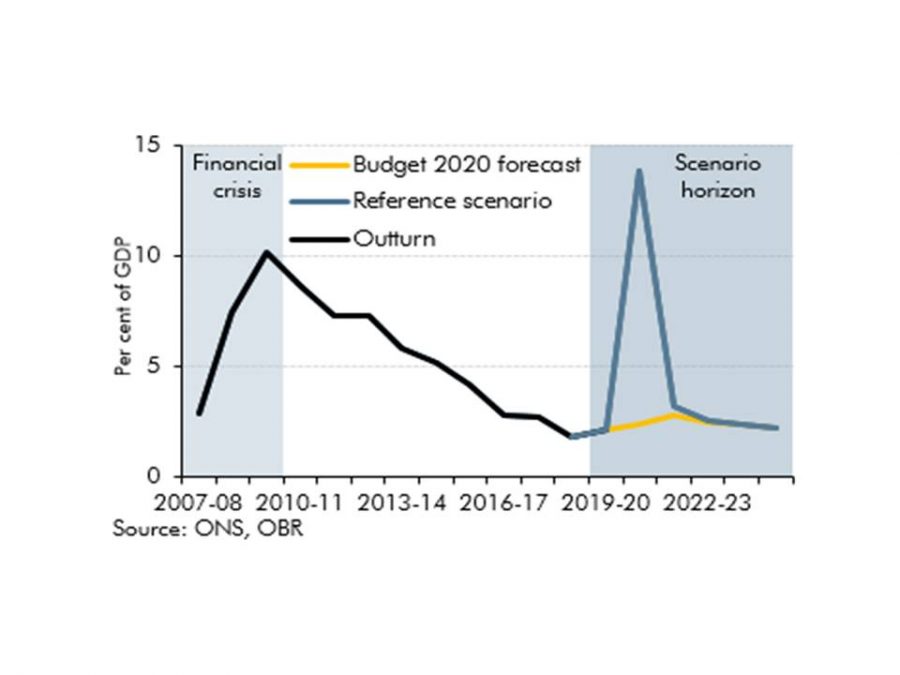

By far the most enduring effect of the pandemic is expected to show up in the UK’s fiscal arithmetic. Chart A shows that all of the progress made in reducing the budget deficit during the past decade of austerity will be wiped out in the year ahead. The budget deficit effectively climbs from around 2% of GDP – or £40 billion or so – to a staggering 14% of GDP or approximately £240 billion of extra borrowing. Chart A: the pandemic has undone all of the decline in debt from austerity

Chart A: the pandemic has undone all of the decline in debt from austerity

This takes the outstanding level of debt to around 100% of GDP. Even after growth resumes in 2021, it only drops back to about 93% of GDP. It almost begs the question of what the austerity – and the damage it caused – was for? Of course, the answer could be that without reducing the deficit to current levels then the increase in the fiscal deficit would have been even bigger.

Nevertheless, the pandemic will be felt in greater pressure on the public finances in the years ahead, and this means tough decisions will have to be made about prioritising what the most critical aspects of public expenditure are. Tax increases seem inevitable, but on what and to what effect on incentives and productivity? How long can interest rates stay at 0.1% given the big increase in money supply from funding the fiscal deficit via the banking system and increased QE, and what happens when they rise?

Thus, the coronavirus has sharpened the focus on several issues, such as how to fund the NHS and how to treat the societal costs of caring for the elderly. Other questions – on how to solve the social housing crisis and provide a better standard of living for ‘essential workers’ loom large, as does negotiating trade deals for the UK’s future outside of the EU.

All this may be occurring at a time of increasing protectionism and a new cold war. Let’s hope it’s not a repeat of the ‘roaring 20s’ of a century ago, with economic nationalism, ‘beggar thy neighbour trade’ policies and misguided domestic policy actions.