Framed as a budget to shrink debt and control inflation, Jeremy Hunt’s statement in the fifth fiscal event of this year essentially left most of the heavy lifting to 2025 and beyond. Of the measures announced, some three quarters were spending cuts, and just one quarter were tax increases. Of the £61.7 billion fiscal tightening announced up to 2027 / 28, only £19 billion occurs before 2024/25.

That implies that beyond 2025, most of the tightening will come from tax increases, but spending will also be cut. Still, the over-tightening of fiscal policy during a recession should be kept to a minimum, as it will shrink the economy more than it would otherwise for no apparent net gain. The chancellor tried to be fair with tax rises for the wealthier alongside benefit increases for the poorest. However, there are political implications as it leaves the bulk of fiscal tightening to after the next general election.

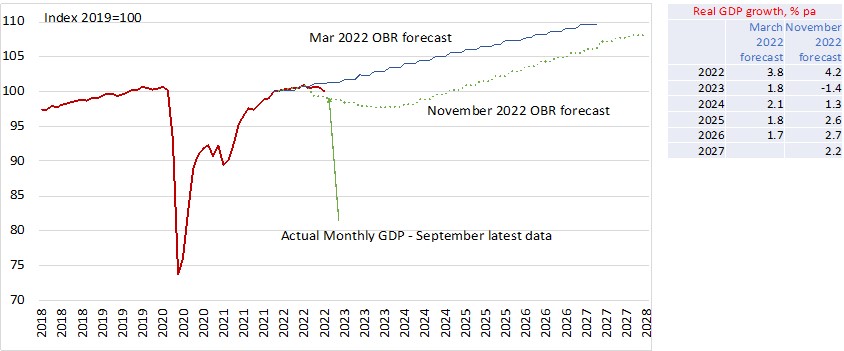

Overall, the budget forecasts make for grim reading over the next couple of years, with the contraction in GDP forecast to be 1.4% in 2023 and 2% in total between now and the end of next year. Taxation will reach the highest level since WW2, and government debt will remain around 100% of GDP. Although recovery is forecast to be underway by 2024, the economy will only achieve its 2019 peak by 2025. That is a bleak picture for living standards by any measure.

There is a risk of overdoing tightening, as the fall in price inflation in 2024 suggests. One should not lose sight of the fact that this was a supply-side shock, aided by too fast growth in money supply. The rapid growth in the latter is reversing, led by higher interest rates and quantitative tightening or QT, see chart. But the inflation target is plus 2%, not minus 2%, so the price deflation in the OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility)’s forecast in 2024 suggests that too much tightening is underway, making the economy weaker and people unnecessarily poorer. That is undoubtedly one policy error that will be reversed relatively quickly when it becomes apparent to the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) that interest rates are too high and deliver falling prices rather than target inflation.

OBR made clear its view of the Budget

The OBR could not be more explicit about the budget measures’ economic impact: ‘Despite £100bn in government support, living standards will fall 7% over the next two years. £60bn in tax rises and spending cuts will arrest the rise in debt by the mid-2020s but will still leave the debt stock £400bn higher than at the end of their March 2020 forecast. A doubling of interest rates will push the UK’s debt interest burden to an all-time high, leaving public finances more vulnerable to future shocks and shifts in financial market sentiment’.

Thus, further action or faster economic growth is required to reduce the debt burden. But a combination of higher energy costs, and the reduction in real spending for households and businesses from higher inflation and higher interest rates, will push the economy into a downturn that will last until 2024. Economic output will not surpass the pre-pandemic output peak until Q1 2025.

As the OBR pointed out, this means a 7% fall in living standards over the coming few years as unemployment rises, and inflation exceeds income, creating the worst hit to standards of living since 1948. Given this forecast, the economic assumptions beyond 2024 are difficult to reconcile, with GDP forecast growth of 2.6% per annum from 2006 to 2028.

Productivity is key to UK recovery

It’s challenging to see where the pick-up in economic growth will come from in the years ahead without supply-side reforms. Uncertainty has hit private sector business investment. The government plans to freeze its capital spending, which is effectively a big cut compared to previous plans, after severe reductions between 2010 and 2018. Unemployment will rise, but little in the Budget has been done to reduce labour force inactivity rates, which would also help boost productivity. In short, there is little new thinking about how supply-side reform can drive UK economic growth.

Looking at OBR forecasts for the UK’s long-term potential growth suggests that productivity will struggle to recover when growth in the labour force is stagnant or slowing and business investment recovers, which means that long-term growth drivers are barely shifting.

But the credibility of this Budget must also be seen in the context of the last six months of three different governments and five significant fiscal events. They started with Rishi Sunak’s Budget as Chancellor in March this year and ended with the 17th of November’s autumn statement with Sunak as Prime Minister. So, much can change in a short time. And there was some good news in the forecasts from the OBR, for example, that inflation will fall significantly – and turn negative in 2024 – implying that interest rates could come down very rapidly indeed, and that unemployment will rise only modestly.

Some good news?

But there was more implied good news: short-term and long-term interest rates could dramatically fall if inflation performs as is forecast. That will ease the burden on businesses and households and help growth adjust upward, and interest rate cuts will be the catalyst that kick-starts the economic recovery.

Servicing the government’s debt burden too will fall dramatically if long-term interest rates were to decline, leaving more for spending on some of the social challenges, particularly from an ageing population that the UK will face as it looks towards the 2030s.

The war in Ukraine could come to a quicker end, and energy prices could fall more sharply than currently priced in futures markets. The UK’s relationship with its key trading partners in Europe could be reset, boosting economic activity. There could be planning reform for housing and business development, which could also lift UK economic growth, particularly if combined with reform of skills and apprenticeships R&D and new infrastructure investments that drive the next generation of technological innovations.

Unemployment remains low

Although UK unemployment is low by historical standards, lack of skilled and unskilled labour is a factor holding back productivity, as is reduced access to our largest trading partners. As the OBR points out, UK trade intensity has declined. But high inactivity rates and unfilled vacancies are signs of productivity gains foregone.

But forecasts in the last decade have shown us that things can change quite rapidly, and we can’t always assume that it’s for the worse. There are opportunities for change which may not appear very apparent now but are still possible if the right policy decisions are made.

We know, for instance, that the pace of technological change is rapid, which means that some of the costs of seizing some of the opportunities may well be cheaper and coincide with the need to grow productivity. Moreover, an ageing population carries some potential benefits: a rise in savings rates is likely – based on Japan’s experience – as more people money aside just ahead of reaching retirement age.

That implies more funds available both for governments to use productively and for the private sector to borrow more cheaply as a rising savings supply reduces the cost of borrowing – one only need look at Japan’s experience to see that. Suppose significant amounts of that money are used to invest in growth-enhancing technologies and opportunities. Ageing also limits the rise in unemployment, since there will be a shortage of critical workers across a range of industries, reducing the hit to employment income in the aftermath of the recession.

Recovery to be helped by structural factors & lower interest rates

Indeed, the challenge of meeting net zero implies that investments are crucial in emissions-reducing technologies. If emissions per unit of GDP fall in the way that energy intensity as a share of GDP has fallen in the last 40 years in the UK and the world, then there are plenty of efficiency gains to be made. Reducing the energy loss from UK homes, investing in efficient emissions production capabilities, clean energy and like activities could have similar dramatic outcomes.

However, these are all long-term trends; in the short term, the challenge is getting through the next few years. Here, there is some hope that, as the chart of inflation and interest rates shows, the fall in price inflation should lead to an equally sharp fall in interest rate, which should help the economy start the long process of recovery. But it needs urgent supply-side reform and a vision of the future, which for now seems sadly lacking.