Ahead of the announcement of the third fiscal event the Labour administration has had since winning the General Election last year, let’s delve into the second budget to look at forecast errors and why they matter.

A significant issue has surfaced: for the second time in a row, the chancellor is compelled to raise new taxes. This predicament has arisen due to the Office of Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) consistent overestimation of revenues and underestimation of spending, which has resulted in a larger fiscal gap than anticipated. While no forecast is perfect and the unexpected cannot be predicted, a forecaster’s job is to take these things into when making their assessments.

Frequent fiscal forecast misses have far-reaching implications for the government’s credibility in managing the country’s budget. The resultant higher long-term interest rates lead to increased borrowing costs, thereby reducing the government’s financial capacity to meet other essential demands, as a greater than anticipated portion of tax receipts are diverted to servicing the debt.

In this article, I try to unpick what’s going on to see whether they’re overestimating growth, overestimating receipts, underestimating spending or, indeed, all three. In my next blog, I’ll go further, considering the implications of these persistent errors.

A 20-Year Review of Forecast Errors, Fiscal Drift, and Political Optimism

By pinpointing the factors contributing to the larger-than-expected deficit, we can devise corrective measures. These could include refining the forecasting methods, adjusting the budget allocation process, or implementing stricter spending oversight. Such actions could correct the forecasting error, instill greater confidence in the government’s economic management, reduce borrowing costs, and free up additional funds for critical public spending.

For over two decades, UK fiscal policy has been guided by forecasts that rarely align with the outcomes they predict. Whether under the Treasury’s direct control or the OBR, projections of growth, borrowing, and spending have consistently misfired – often with profound consequences for public services, investor confidence, and political credibility. The same is true for different governments. Across all of them, the problem persists, suggesting a structural rather than a political issue.

The Institutional Shift: From Treasury to OBR

Before 2010, fiscal forecasts were produced by the Treasury, under the direct influence of the Chancellor. These projections often reflected political imperatives – optimistic growth assumptions, understated borrowing needs, and spending plans designed to support electoral narratives.

The creation of the OBR in 2010 by George Osborne and the incoming Conservative government was intended to depoliticise this process and, by extension, eliminate the biases perceived to be generating errors. As an independent body, the OBR would provide objective forecasts to underpin fiscal decisions. Yet independence has not guaranteed accuracy. The OBR’s track record reveals a persistent optimism bias, particularly in its medium-term projections.

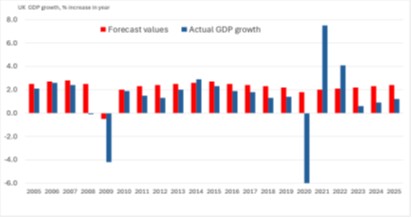

GDP Growth Forecast Errors

One of the most striking patterns in UK fiscal forecasting is the consistent overestimation of GDP growth. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, both the Treasury and the OBR assumed a swift return to pre-crisis productivity trends. Forecasts made between 2010 and 2015 projected annual economic growth of 2.5–2.7%, underpinned by expectations of a productivity rebound. That rebound never materialised. Actual growth hovered closer to 1.5% and, in some years – such as 2012 and 2018 – barely exceeded 1%.

This optimism had cascading effects. Tax revenues fell short of expectations, borrowing exceeded targets, and spending plans based on higher growth had to be revised mid-year. The gap between forecast and reality was not just a technical error – it shaped the fiscal landscape for a decade and more.

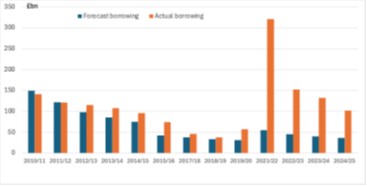

Public Sector Net Borrowing errors

Forecasting errors in borrowing have been equally stark. In 2013, the OBR projected public sector net borrowing of £42 billion for 2015-16. The actual figure was £74 billion – nearly double the forecast. Similar discrepancies occurred throughout the 2010s, with borrowing consistently underestimated. The most dramatic divergence came in 2020-21, when the COVID-19 Pandemic triggered emergency spending. The OBR’s initial forecast of £55 billion was dwarfed by the actual borrowing of £321 billion. Of course, there was no way that this could have been predicted – it was, after all, a once-in-a-hundred-year event, as was the Global Financial Crisis. Together, the two events have amplified what was already occurring, a growing forecasting problem.

These errors forced reactive policymaking. Emergency budgets, mid-year spending cuts, and revised fiscal rules became routine. The credibility of fiscal planning suffered, and investors began to price in not only economic risk but also forecasting risk.

Spending Pressures: Welfare and Health

But forecasting errors were not confined to revenue and borrowing. Spending projections – particularly in welfare and healthcare – also proved unreliable. The OBR consistently underestimated demand-led spending, failing to account for demographic pressures, policy implementation cost overruns, and structural shifts in service delivery due to technology.

For example, the triple lock on pensions, introduced in 2010, significantly increased welfare spending. Similarly, repeated boosts to NHS funding – often announced outside the formal Budget process – added billions to annual expenditure. These decisions were politically widespread and made by the government, but were fiscally disruptive, especially when they were not included in fiscal projections. That is clearly not the fault of the OBR or Treasury. Still, an outside observer could argue they should have been factored into the estimates, as they clearly indicated an upward drift, regardless of what was happening in the economy.

In short, a systematic bias towards higher spending would be seen because of their rising share of total expenditure, and the question arises: what if their share rose more than expected or was budgeted? What would be the effect on an overall budget increase in sensitivity to changes in those variables? One such sensitivity suggests that the ageing population requires more healthcare and draws on pensions for longer.

And so we have a history of fiscal forecast errors. Look out for my next blog, where I’ll be examining the implications of these persistent misses.