Income: 19s,8d

Expenditure: 18s,8d

Result: Happiness said Micawber

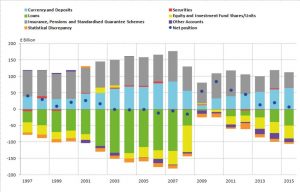

If only life was that simple. But looking at the UK’s financial balances can yield useful information about the build-up of excesses in the real economy. Recent figures from the ONS show that the UK’s household saving ratio – defined as their total expenditure relative to disposable income – fell to its lowest levels since the records were compiled on a similar basis in the early 1960s. But another measure of the financial position of households which calculates its net balance – taking account of its assets and liabilities (see chart) – is often regarded as a better guide to its true financial health than the saving ratio.

Defining savings

Yet data shows that that net position is deteriorating – and is at a level not seen until just prior to the financial crisis in 2008.

Net sector financial balances (government, companies, households, overseas) must sum to zero for the economy as a whole. This is because one sector’s surplus or deficit must be another sector’s surplus or deficit. If the domestic sectors (government, companies, households) are in a net surplus or deficit position as a whole, then the overseas sector balances the accounts.

A domestic financial deficit implies borrowing from overseas, while a surplus implies lending overseas. In terms of the balance of payments: net domestic borrowing means a surplus on the capital account as money comes into the country and net lending means a negative as money flows out of the country.

In balance of payments parlance and accounting rules: a positive sign on the capital account is a negative on the current account and vice versa. But as I have shown, the current account deficit is really a function of the domestic saving investment gap. Since the UK tends to run a domestic financial deficit (domestic savings are insufficient for all its borrowing needs), it borrows from overseas. This means it runs a persistent current account deficit.

Should a deteriorating financial balance concern us?

The savings ratio and the sector balance are not exactly the same thing but their trends tend to move in the same direction. The figures below are from 2016, and if that trend continued into 2017, UK households may once again be net borrowers from other sectors in the UK.

If so, what does this mean for economic stability? Well, for one thing it suggests that the current account deficit will deteriorate. Right on cue, ONS figures show that the UK current account deficit grew in Q1 2017, to £16.9 billion, compared to £12.1 billion in Q4 2016. It also suggests that the economy may be unbalanced. If, for example, consumer confidence took a dive, households may pull back on spending or restore their financial balance to a healthier position. This would mean higher saving, less spending and so weaker economic activity.

An unbalanced domestic financial position – never a borrower be?

Between 2005 and 2008, households started to become net borrowers, acquiring an increasing number of loans relative to deposits and other assets. Following the downturn, households acquired far fewer loans and only acquired a slightly smaller amount of assets, to become net lenders to other sectors. This peaked in 2010 when UK households lent £84.5 billion. Households then started to move towards becoming net borrowers as the acquisition of liabilities increased. In 2015, households remained slight net lenders, by £7.5 billion, driven by an increase in acquisition of loans and equity and investment fund shares and only slight changes in the values of assets.

Over the same period, government debt ballooned, with the deficit since being cut (although by no means eliminated) by a decrease in government expenditure – so-called austerity measures. Businesses have been increasing their savings and cash surpluses have grown since the Global Financial Crisis. What this means though is that they have failed to invest in plant and machinery – the tools to drive sustainable economic growth.

The risk of a fall consumer confidence is rising

With the UK’s EU exit underway, global economic fragility and heightened uncertainty, high levels of inflation and signs of a slowing in the domestic economy, the household sector’s financial balance suggest that the economy is perhaps as risky today as in the run up to the 2008 downturn – even though the financial balances had been in negative territory for a few years before the crisis. But it may not take a return to that position to cause a retrenchment today. This may have implications for bank rate, and so these are figures that will need to be monitored carefully in the quarters ahead.