The US Federal Reserve or Fed, and the UK Central Bank or the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC,) both made the decision on whether to cut interest rates on the same day, although, given the time difference, it happened at different points. The US Fed cut interest rates by ½% to a range of 4.75% to 5%, but the UK central bank left its rates on hold. The latter’s decision to leave rates on hold left its interest rates at 5% after a ¼% point cut from 5 ¼% at its August meeting. Many declared the US Fed’s cut momentous, because it was during an election campaign, and the size of the cut certainly surprised financial markets, which is why bonds rallied and equities rose.

Interestingly, if one looks at the economic data that the Fed used to justify its rate cut, one can see that they are stronger than the UK’s, even though the MPC decided to leave its interest rates on hold. So it’s worth exploring what data we can use to compare the decisions we’re seeing from each country and judge what that tells us about the mindset of each central bank.

Economics and politics in play?

As a background, the Fed’s decision was in the middle of an election cycle, with presidential and state congressional elections taking place on November 5th. Yet the Fed still cut interest rates in what the opposition could see as a partisan move in the ongoing election campaign. This decision could potentially influence the economic conditions leading up to the elections. It ignored that potential brickbat and focused on the economic rationale because its decisions should be based on economics, not politics.

Recall that during the UK election campaign, the UK’s MPC or central bank had the opportunity to cut interest rates but chose not to; instead, it cut them on August 1st, after the election had already taken place. This decision could have been influenced by the MPC’s desire to maintain stability during the election period. And, leaving the decision until after the election could have been a strategic move to avoid any potential political implications.

Of course, one could argue that they did that only on economic grounds. Still, the difference between the two central banks is worth mentioning because, after all, both had the opportunity to cut interest rates during an election campaign – one did, and the other didn’t. That may say something about each central bank’s confidence and willingness to act quickly or preemptively.

Interest rate intentions

The Bank of England’s decision to leave interest rates at 5% at its meeting, which ended on the 19th September when the MPC announced the decision, was eight to one amongst the nine voting members. The US Fed’s decision to cut interest rates was unanimous, but one member voted for a cut of 1/4 of a per cent. That was the first time since 2005 that there was a difference in the voting pattern on the committee.

At the same time, the US Fed has said that it expects interest rates to be 1.5 percentage points lower than the current rate by the end of next year. That means rates fall to 3.25%. The Bank of England has said nothing about its intentions other than that it will move cautiously, and that it wants inflation to fall below the 2% target, and be confident that it will stay below target, before it’s willing to act.

However, the US Fed has implied that it could cut another 3/4 of a percentage point before the end of this year, which would bring rates down to 4%. This expectation of further rate cuts could signal the Fed’s confidence in the economy’s future performance, or it could be a response to potential economic challenges. What’s certain is the guidance is clear and unambiguous and will be closely watched by financial market participants.

The Fed seems not to mind being a hostage to fortune and changing its mind if the data changes. The latter is something a well-known UK economist, John Maynard Keynes, once famously said: that policymakers should be willing to change their minds if the facts change.

Different attitudes to risk and growth

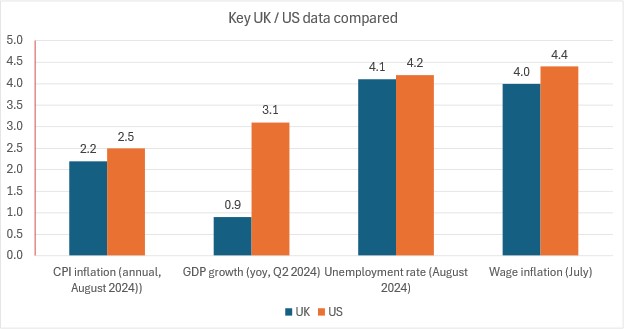

As we can see from the chart below, the UK has weaker economic growth than the US and a lower inflation rate, as well as slightly lower wage inflation. However, it does have a similar unemployment rate.

Based on this data, one would think the desire to cut rates would be stronger in the UK than in the US, but that is not the case.

More remarkably, the US is willing to cut even though its growth rate year on year is over 3%, whilst the UK is willing to hold interest rates at 5% even though its growth rate is only 0.9% above year-ago levels. That sums up the difference between the two central banks. Even if the Bank of England thinks that the UK’s current natural growth rate is 0.3% a quarter or 1.2% per year, the current rate is still below that figure, and there is slack in the labour market.

That is truly a story of two central banks; one not worried about taking risks because it would be willing to reverse course quite quickly if the data suggests otherwise, and the other perhaps scarred by being too slow to raise interest rates in the face of higher inflation a couple of years ago and now looking too fearful of lowering interest rates at a time when it’s clear to many others that the economy needs a boost.