My first prediction is that I am confident that only some of the projections people make will fully capture what happens this year. One of the lessons of the last few years is that more disruptive events are occurring more frequently than before, causing more uncertainty.

Some things will continue this year: technological change will continue to accelerate. Its disruptive effects on economies and society will continue and be even more challenging over the next few years. AI and machine learning are reaching critical levels in some sectors, with their disruptive impact potential likely to lead to policy reactions, for example, in education and the arts.

The powerful effect of demographic change is still unfolding, leading to shortages of workers in some countries and, therefore, higher pay. But it conflicts with policies of tight control of immigration in some countries where domestic labour shortages are beginning to show up. That list includes the UK.

India will overtake China as the world’s most populous country this year, critically driven by working-age population growth. Indian economic growth could therefore accelerate in the years ahead (as China’s did when it went through something similar). But for this to happen, India would have to copy China’s opening to the world, which occurred because of the policies of Deng shao ping. That seems unlikely on current perceptions and therein would lie the surprise.

One big event this year is the abandonment of the strict COVID policy that China has operated and opened fully to the rest of the world from the 8th of January. That has enormous implications for the world economy, with higher growth and inflation. There are also worries about the health risks of new variants.

Regarding specific 2023 economic forecasts, the world economy will grow by between 2.5 and 3%, some half a per cent below its long-term growth trend. It will not, therefore, experience a recession in 2023, and that’s got to be seen as good news. Most of that growth will be driven by the emerging economies in Asia. Energy-exporting countries that have significantly benefited from higher oil and gas prices will also outperform.

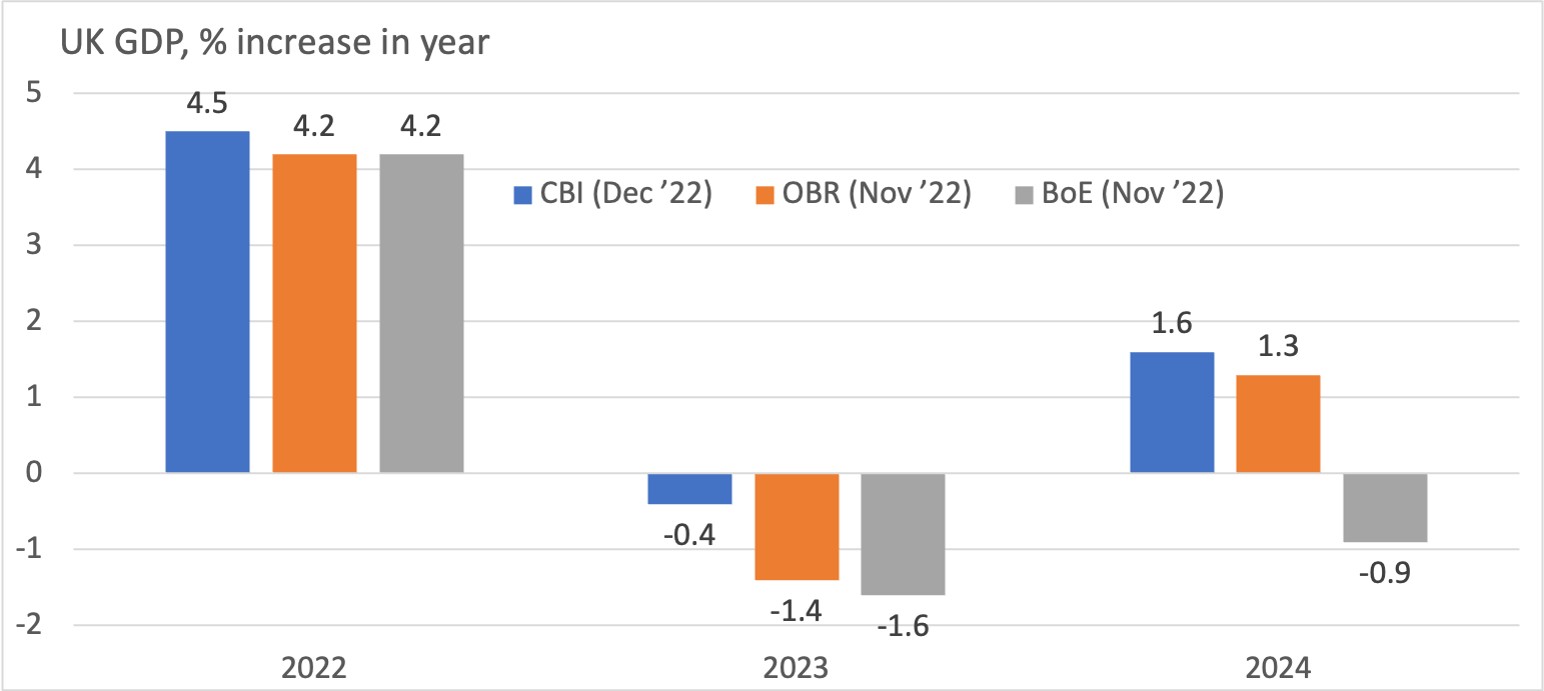

The US and Europe will avoid an annual fall in output, though a quarter or so of shrinking GDP cannot be ruled out. The latest economic growth estimates from the Office for National Statistics show that the UK economy is now 0.8% below its pre-pandemic level and is the only G7 economy in that position. So much for the Brexit message that the UK economy was held back by being a member of the EU.

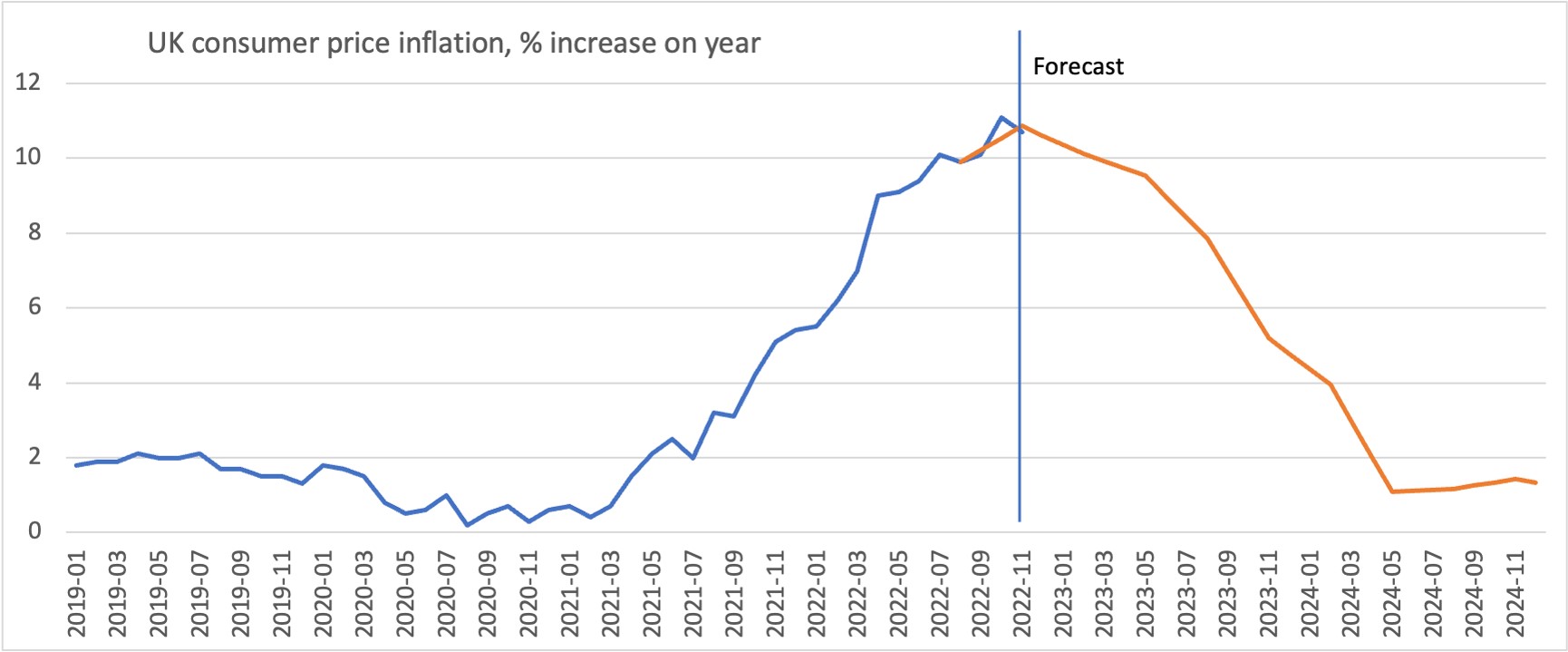

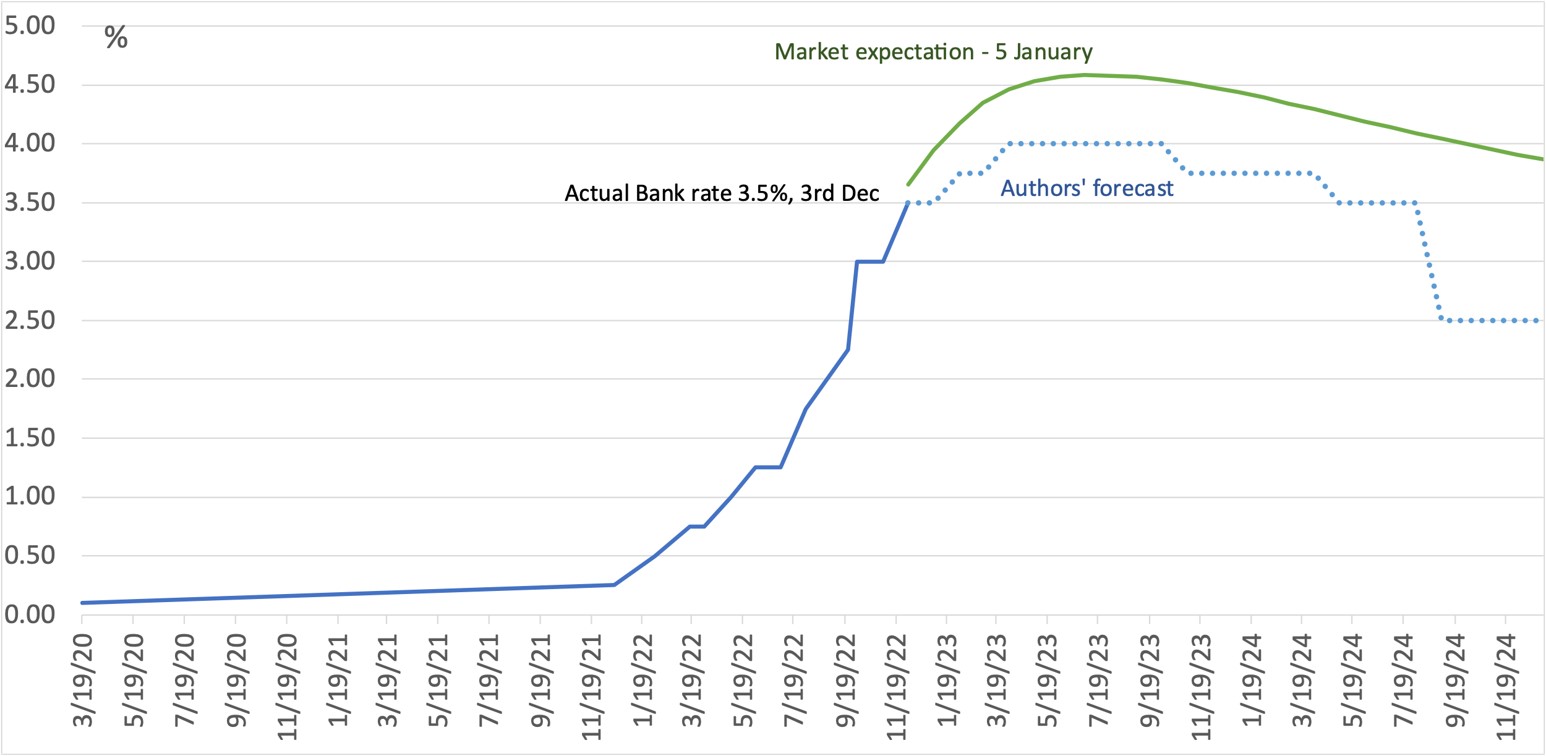

That is the context within which there’s been a surge in price inflation. The peak in consumer price inflation will be reached in the first half of 2023, and inflation will come off quite rapidly in the second half. Consequently, the peak in interest rates will also be in the first half of 2023, and some countries could cut by the end of the year.

Global financial markets in the second half of 2023 – particularly the final quarter – will be bouncing back due to the peak in inflation, and interest rates have passed and looking ahead to a pickup in global economic activity in 2024. Bond markets will start to bounce back once it’s clear that the peak in interest rates has passed. The bounce in global equity markets could wait until the second half of the year when it’s more apparent that growth is consolidating and that the next move in interest rates will be down as markets begin to look out to 2024. Lower energy prices and better recovery prospects will boost other commodities such as grain, wheat, and metals.

The UK will be the weakest performing of the G7 economies, shrinking where the average G7 economy may not. But paradoxically, this could mean that its interest rates have more room to be lowered before the end of the year than in some other economies. Therefore, UK equity and bond markets have the potential to outperform some of the major economies.

UK consumer price inflation will be back to around 4% by the end of the year. Hence, official interest rates will either be cut in late 2023 or early 2024. One factor that many are ignoring or not taking enough into account is that the reversing of QE – so the selling of bonds by the Bank of England – will lead to a sharp contraction in UK money supply growth, possibly even a decline. Such an outcome will almost certainly lead to significant reductions in inflation in 2024, perhaps even into negative territory before the end of 2024.

There is no economic justification for the UK Bank rate to rise above 4%, as financial markets currently expect. If rates go above 4%, the outcome will be unnecessarily weak economic growth and the prospect of negative inflation towards the end of 2024. The Bank of England would then have made a mistake with a tight interest rate policy on the upside and loose on the downside and would have to reverse course rapidly when this becomes apparent in 2024.

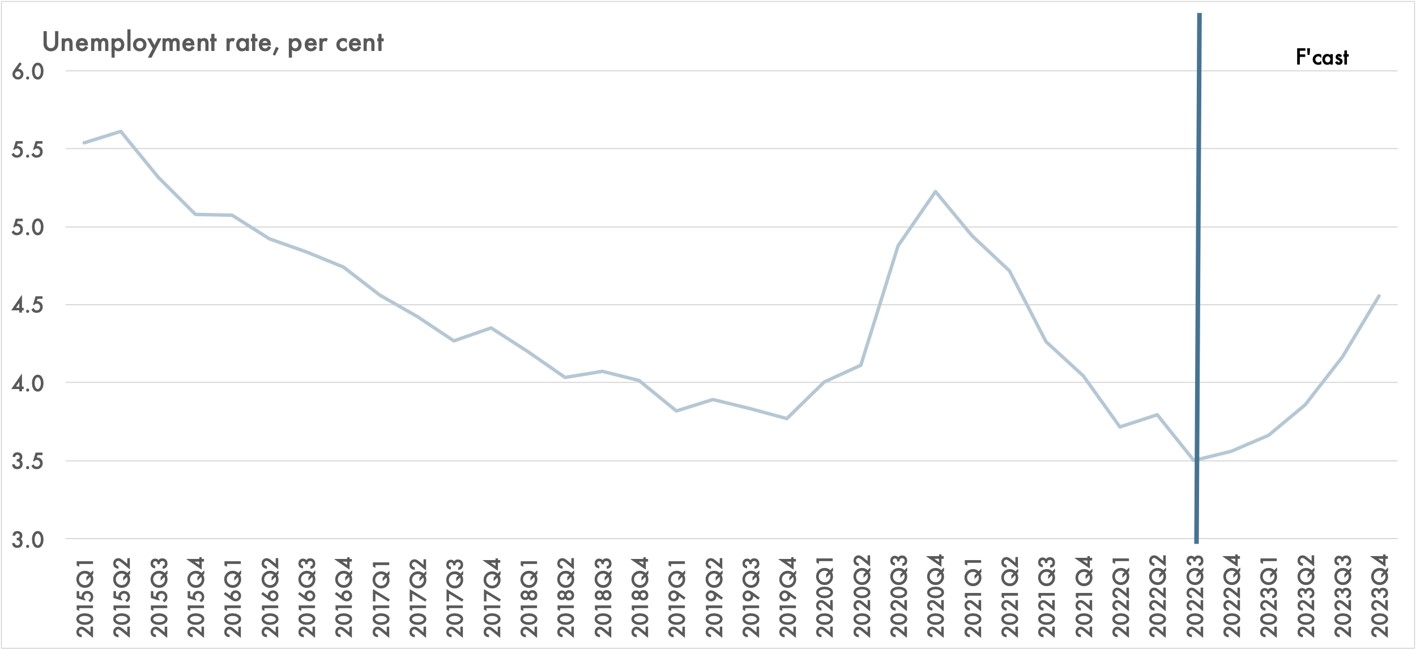

One spot of good news is that unemployment won’t rise very much. Vacancies are incredibly high, and there are labour shortages in some key sectors, both for skilled and unskilled workers. That will help to mitigate the pain of the cost-of-living crisis because of the rise in price inflation and the poor level of productivity, which has meant that pay growth has also been weak. The strikes in the public sector won’t go away until the government settles because the austerity that started under George Osborne, which kept private sector pay growth at about 1 to 2%, has meant that millions of public sector workers have had inflation-adjusted cuts in living standards of between 10 and 30%.

The currency will remain weak because the UK has a significant current account deficit and borrows from overseas investors to fund it. Meanwhile, house price inflation will likely fall by about 5 to 10% this year. However, that will only take the level of prices back to where they were 12 months ago, which means they are still beyond the reach of most buyers. At around 7 to 8 times the average income, they continue to reflect the sclerotic nature of the UK’s planning system, which is one of the reasons why the economy continues to underperform.