Some of the policies announced by the Bank of England at its last meeting (21 September 2023) are flying under the financial markets radar. Although attention was rightly focused on the Bank of England’s decision to leave interest rates on hold at 5.25% – the first hold in 14 meetings –another announcement at the meeting was almost as crucial for inflation and economic growth.

Alongside the decision to hold interest rates, there was confirmation that there would be a further £100bn of QT occurring between October this year and September next year after the successful selling of £100bn in the previous 12 months. Starting in October, that would entail selling £8.3bn monthly for the next 12 months. The committee estimates that this would take the total amount of bonds held under the QE program down to £658bn by the end of September 2024. That would equate to a £200bn reduction over two years. Total debt securities held by the Bank of England have fallen by £162 billion from their peak in 2020, see Chart 1.

This shows that the Bank of England is serious about reversing QE. But this withdrawal of liquidity has consequences for the economy and inflation, which, of course, is the aim of quantitative measures. Reducing the money available in the economy can lower spending and demand by making money scarcer and more expensive. That will result in lower inflation and weaker economic activity than otherwise.

UK money supply, credit and lending data released on 29 September showed that annual growth in M4 was minus 0.6% in August compared with the same period the year before. That was the first fall in broad money supply since February 2010. Just two years after that fall, consumer price inflation dropped to zero from an annual rate of 2%. In chart 2, we have advanced the yearly monthly per cent changes in M4 by 18 months to show how closely it correlates to subsequent changes in price inflation. The lag of the influence may be ‘long and varied’, but it’s clear that a reduction of monetary growth eventually impacts the pace of inflation.

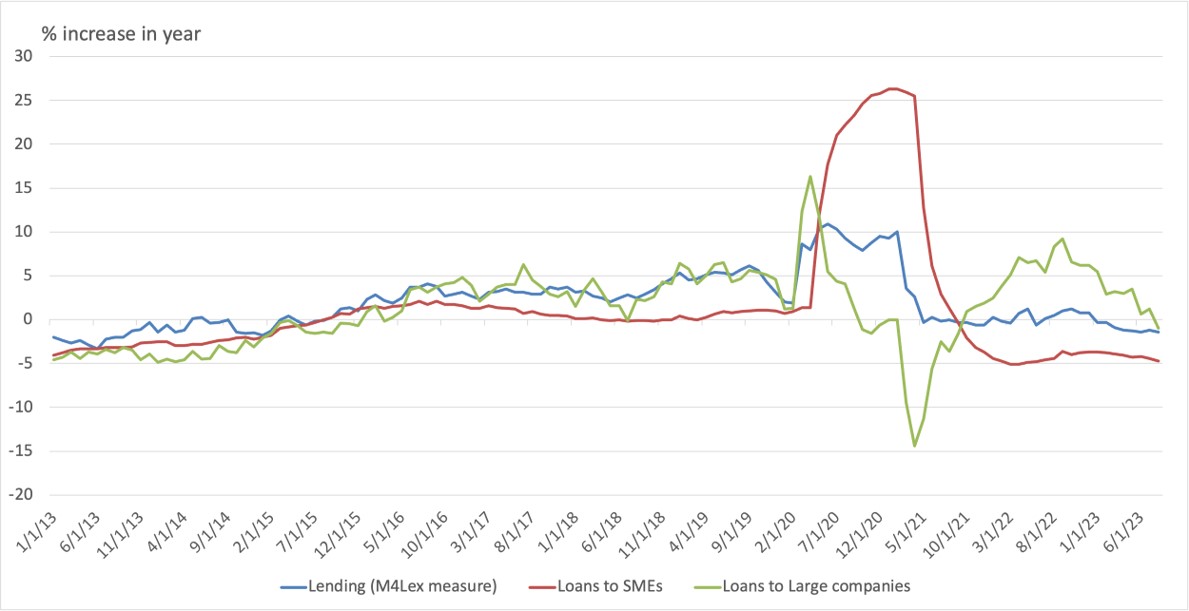

On top of this, however, monetary data released in September 2023 (for August) also showed that small and medium-sized firms and large businesses are repaying debt, see chart 3. That makes it the first time in about 18 months that small and medium-sized firms are doing this simultaneously. Households are similarly retrenching, drawing on deposits to fund current spending as higher mortgage rates suck discretionary spending out of consumers’ wallets.

But it should come as no surprise with high nominal interest rates under contraction in money supply, making it both pricier and scarcer. That is a precursor to weaker investment spending and lower employment trends in the months ahead.

Purchasing managers’ data for September showed that services and manufacturing activity are below the crucial 50 level, suggesting a contraction in output in the months ahead if it stays in negative territory, see chart 4.

The Bank of England wanted an economic slowdown to take the heat out of inflation. With UK consumer price inflation roughly twice that of the European and American average, it clearly feels that inflation has a lot further to fall before they can call the peak in rates. But monetary policy acts with a lag (and some 50% of the tightening has yet to impact the economy), and if we are already seeing these indications of the coming economic slowdown and how much inflation could fall, then the risk of undershooting the 2% inflation target is rising the longer interest rates stay where they are, never mind rise further.

So, in 2024, interest rates will almost certainly fall or at least should. The question is how soon it becomes apparent to the Bank of England that they must act. Knowing market pricing behaviors, it will probably turn on a ‘ninepence’ and it will predict significant interest rate cuts well ahead of the Bank of England doing so. I expect that to happen sooner in 2024 than later. Avoiding a deflationary episode is something that should be on the top of the Bank of England’s agenda in 2024.