The spending review is a forward-looking process by which the government sets departmental budgets for future years, including for key sectors such as the NHS, Education, Defence and Transport. It also determines the government’s day-to-day running administration costs and capital spending for investments in public services and military equipment. This process sets day-to-day expenditures for three years and investment spending for a five-year period. A review of the plan is conducted every two years. The aim is to demonstrate the government’s commitment to long-term planning and fiscal responsibility, thereby promoting stability.

In the Spending Review (SR) 2025, the government has broken it into two ‘phases’, as it calls them. Phase 1 of the 2025 SR is to reset departmental budget spending for 2024/25 and to set budgets for 2025/6. In Phase 2, just released, the government has finalised department budgets for the whole of the 2025 SR period. That means setting resource budgets for day-to-day spending to 2028/9 and capital spending for 2029/30.

But there was so much detail in the figures that were released that it would be easy to get confused and miss the big picture. That’s why it’s essential to understand that the amount being spent by the government is directly linked to the rate of economic growth and the taxes it can levy, and the spending that it can do as a result, plus the additional borrowing it’s able to derive from issuing debt instruments, such as bonds or gilts to institutional investors.

If the government borrows, it will have to pay interest on the loan, and it can only do so by generating revenue from taxes derived from future economic growth. However, the increase in borrowing and subsequent interest payments it incurs means that in repaying the interest and capital borrowed, it also reduces the room to spend for day-to-day departmental purposes and on capital spending.

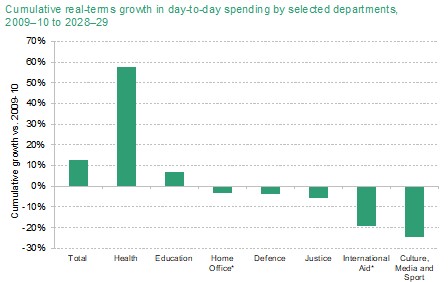

There is also a distinction between real spending, which is adjusted for inflation, and nominal spending. That is because an increase in real expenditure provides additional resources, as it accounts for the effects of consumer price inflation. If we examine Chart 1, we see that only two departments over the period shown (2009/10 to 2028/9) – Health and Education – experienced an increase in real terms, with Health accounting for nearly 60% of the cumulative day-to-day spending. All other departments experienced a cut in real day-to-day spending. International aid, culture, media, and sport have been most severely impacted, with ‘real’ spending cuts of 20 to 25% though defence spending also fell in the period.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Rachel Reeves’s announcement of spending increases in the 2025 SR, which allocated 60% of the total rise in department spending to the Department of Health on a day-to-day basis, did not shock, but perhaps it should have. Of course, this is partly a result of an ageing population, but it also indicates poor productivity and returns on investment. This should mean pressure to ensure a rise in productivity and a better return on health spending in this spending review. Otherwise, we must ask how long one department can take so much of the total Budget, where it will end, and how sustainable it is for other departments to be under-resourced without serious adverse economic, social, and other unintended side effects.

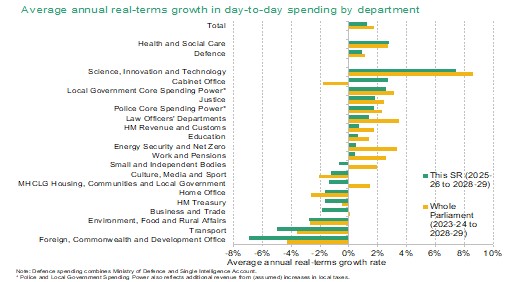

Admittedly, in the current spending review, fewer government departments will see outright cuts, although some, including the Home Office, will. That said, some departments will see real spending grow by less than the 1.3% envelope. In addition, some of the spending that has been allocated is front-loaded, meaning that in the second part of the 2025 SR (years 3, 4, and 5), every department except the protected ones and science and technology sees real spending cuts or growth of less than 1.3% per annum, as shown in Chart 2. For local governments to see a rise in overall spending, for example, council tax will have to rise by 5%.

The latest data for April show a 0.3% decline in UK GDP growth, with a 0.9% year-over-year increase. This outcome challenges the sustainability of the 1.3% increase in government spending and the assumption that the growth of the whole economy in 2025 rises in line with the OBR’s prediction of around 1.9%. With the OBR predicting that tariffs will reduce GDP growth by 0.6% and the OECD and the IMF both reducing UK growth for this year and next to 1 to 1.5% pa, it is no wonder that the spending allocated in this budget is an envelope of just 1.3%.

However, it also highlights the vulnerability of the ‘fiscal headroom’ – which refers to the amount of money the government has available to spend before breaching its fiscal rules – of just £9.9 billion to changing circumstances beyond the control of the government.

Capital Spending

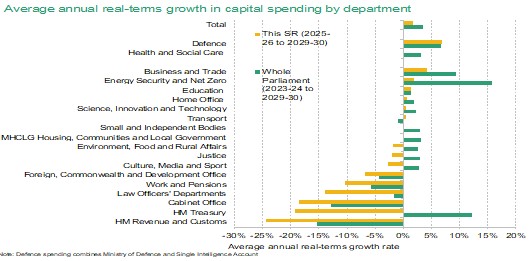

The government’s capital investment choices, as depicted in Chart 3, are not only a reflection of its political decisions but also a crucial indicator of its future direction. This future direction is of utmost importance, as it will have a large impact on the country’s growth and development. Notably, defence, intelligence, and energy emerge as the primary focus areas in the government’s capital spending plans. Worryingly though only 13% of the spending is in the growth focused category, which is expected to pay for all other increases.

However, when examining the average annual growth in real terms by department for the spending review, chart 4, we see a very challenging picture emerging for the government’s ability to invest in a range of departments, with some deep cuts ahead in capital investment in sectors such as Justice, the Cabinet Office, Revenue and Customs, and Aid. Despite the threat of having to borrow more and raise taxes, the pressure on public spending, which stems from the lack of growth in revenue due to a slow growing economy, persists.

It highlights that an emphasis on development boosting productivity to raise the rate of growth and changing the way the economy is managed are all critical to meeting the investment challenges brutally highlighted by the spending review.

That said, the government’s capital expenditure plan, which includes an increase of £130 billion, represents a pivot from the plans outlined by the Conservatives in their March 2024 budget. A portion of this increase, amounting to £15.6 billion, has been earmarked for rail and road projects, with the majority being distributed across the country, particularly in regions outside the southeast.

Furthermore, the government shows its commitment to social welfare by its spending on free school meals for those with Universal Credit, a cap on bus fares at £3, and the cost of free school uniforms. £13.2 billion is allocated over the five years to 2029/30 to the Warm Homes Plan.

Capital will also be invested in a new program called the Affordable Homes Program, with £39 billion allocated over 10 years. One of the areas of good news for many was the announcement that the Sizewell C Nuclear plant will proceed with a government investment of £14.2 billion. It was also accompanied by an announcement to invest in small modular nuclear reactors supplied by Rolls-Royce. That’s probably wise, as it’s not clear how Sizewell C will be built, given that it seems the UK and EDF are the only parties involved, with the Chinese excluded.

In summary, the government has had to make some tough decisions. But they are still borrowing a lot of money and the number of people paying tax and its share of GDP are high. Each of those limits may have been reached. One key question is whether, in the current period of international volatility in bond markets and geoeconomic / political uncertainty, the UK can continue to fund its debt, which accounts for nearly 100% of GDP, including debt interest payments of well over £100 billion per annum for the foreseeable future, without any negative reaction. That remains one of the Chancellor’s most significant risks as we go into the second half of 2025. Considering the uncertainty of winter fuel payment costs – we don’t know how severe or not the next winter will be – and the headroom of just £9.9 billion, the risk of breaking her own fiscal rules remains high, and the Chancellor may yet have to raise taxes in the autumn. Or risk a severe bond market reaction. Nor does it take account of the rise in the size of the state since the Global Financial crisis and Pandemic; spending 45% of GDP while taxes are 38% of GDP. The 8% shortfall implies that either taxes must go up, spending must be cut, or we borrow 6% or more a year for the foreseeable future.