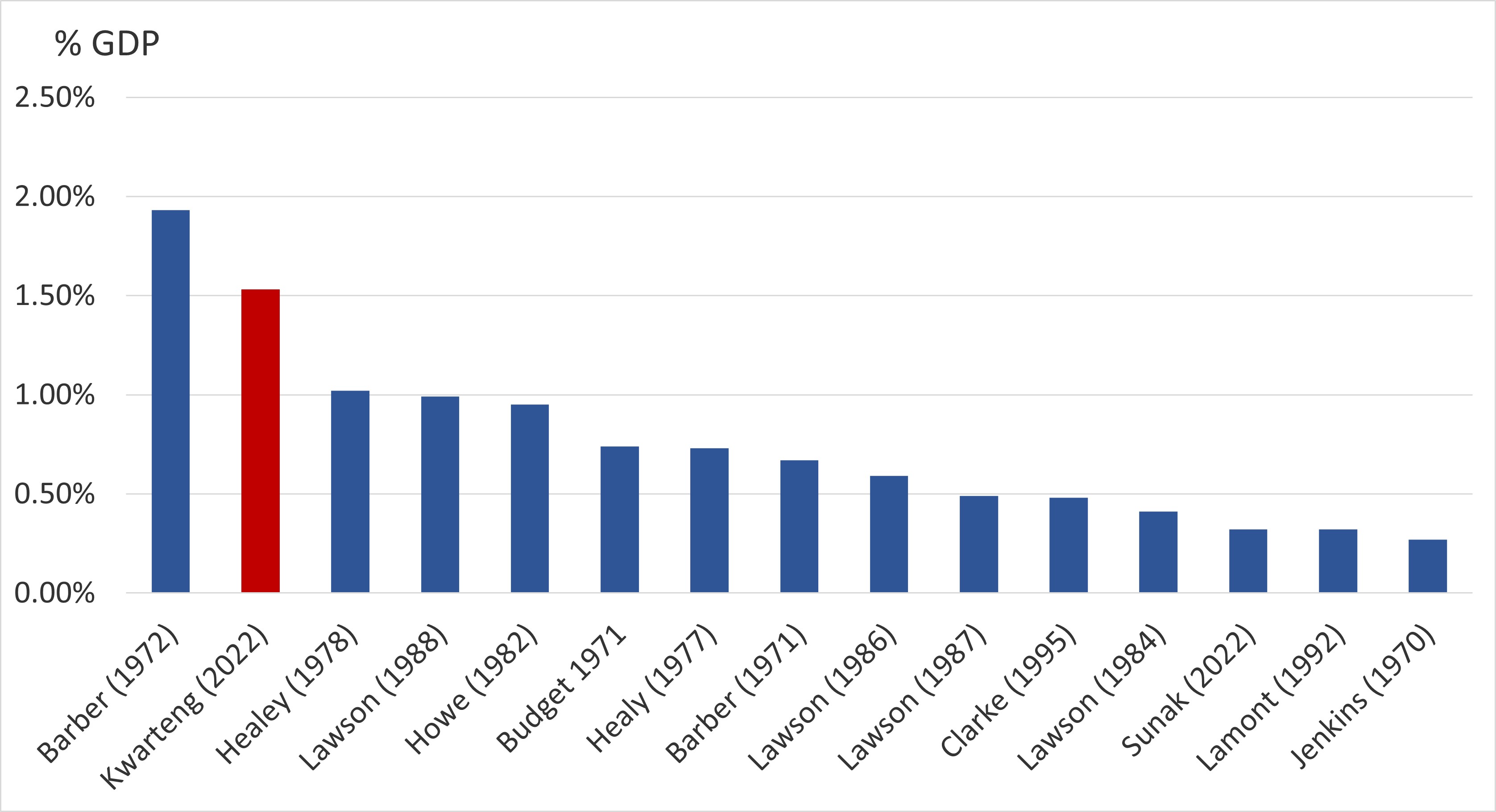

Friday’s mini-Budget was anything but small. It’s the biggest tax-cutting Budget since the ‘Barber’ boom Budget of 1972 or 50 years ago.

Unfortunately, the parallels are not good, as that Budget did not end well. Eventually, it led to the loss of a general election by Conservative prime minister Ted Heath. Time will tell if this Budget leads to the same fate. But it represents a break with the last 12 years of Conservative governments focused on austerity or tight public finances and efforts to help the low-paid.

The big fiscal picture

The scale of the permanent net tax cuts – some two per cent of GDP – will undoubtedly offer a short-term boost to economic growth, perhaps of the order of a ¼% of GDP in 2023 and possibly in 2024. Government borrowing will rise sharply, reaching around £190bn or 7½% of GDP next year, making it the third biggest deficit after the global financial crisis and the Pandemic since WW2. It will likely fall to £100 billion over the next few years once the energy support package ends, but it will remain some £80bn more than this year’s March Budget forecast.

This Budget was about taxes rather than public spending or public services. Those in receipt of benefits did not get anything from Friday’s Budget. Indeed, those on universal benefits may have to work longer hours to achieve the same level of support. The Budget did not support those on low incomes besides what is offered in the energy package. See chart 3 for the income distribution of the tax cuts.

The only public spending support came from maintaining the £2bn compensation offered to public sector bodies by the previous chancellor to compensate for the rise in National Insurance that they would have had to pay for their employees. Beyond this, little was said about public sector pay, for example, and the provision of NHS or care home funding.

Financial reaction adverse so far

Financial markets expect a significant increase in UK government bond issuance, which will inevitably mean higher bond yields. Still, we’re also likely to see a currency fall to encourage foreign investors to hold UK government debt. There are signs that this is already beginning to happen. Bond yields are up to 3%, bets of the peak in UK interest rates have gone above 5%, and the pound is hitting new 37-year lows.

One arm of government will give, and another will take away.

With consumer inflation already above 10%, the Bank of England will likely respond to this demand boost with higher interest rates than they might otherwise have. Indeed, to offset the effects of this Budget, interest rates may be up to half a per cent higher than would otherwise have been the case.

The first move towards this may come at the next MPC meeting in November, when rates could rise by 75 to 100 basis points, taking the Bank Rate to 3% or above. Financial market expectations since the Budget have shifted to interest rates peaking at 5% in 2023 rather than four and three-quarter per cent, and for this peak to persist for longer, with rate cuts not occurring until early 2024 rather than late 2023.

Perhaps that may suit the government politically because the reductions may occur before a general election. Moreover, the worst of the economic slowdown should be over, and price inflation will most certainly be sharply off its peak this year and fall as the energy price rises drop out of the annual measure.

A list of the primary measures in the Budget – a budget for the better off?

Income tax top rate cut to 40%

Bankers’ bonuses cap scrapped

The basic rate of income tax cut to 19% from April 2023

Stamp duty reduced & tax-exempt thresholds increased

NI increases scrapped

IR35 changes to help self-employed

The planned rise in corporation tax scrapped

38 new investment zones announced

Extending investment relief

What would a radical supply-side Budget look like?

The Budget did nod towards some supply-side issues, such as the cut in Stamp Duty and New Investment Zones, but fundamentally the Budget boosted the demand side of the economy, not supply. It’s hard to argue otherwise, with little being done to increase public investment and address issues around skill shortages and the lack of vocational and NVQ level qualifications.

Nor did we see planning reform to allow firms to build more quickly where people want to live at affordable house prices or rents. There was no devolution of business rates to local authority areas and no cuts to those business rates. There was also no boost to public sector housing by allowing local authorities to borrow through the public sector works loans board to fund the building of social housing specifically, or to let local and housing associations do the same thing.

That would be building for rent and not for sale, which would start to compensate for the two million homes across the UK that have been sold since the start of the council house sell-off in October 1980, with only a fraction being built back. It is part of the reason there is such a housing crisis for many young people who cannot afford to buy and live in the areas they grew up in or want to move to. Such reforms might even increase social cohesion.

Interestingly, home ownership in the UK rose from 55% in 1980 to 71% in 2003 but has since fallen back to 62.5% – the 1985 level. This reflects that not enough homes have been built and that we’ve seen rising prices and a lack of ability to get on the housing ladder. For a policy that initially set out to increase homeownership, it’s somewhat ironic that it now appears to be a policy that is reducing home ownership.

These would be radical supply-side initiatives that would boost the long-term growth potential of the UK, but they would likely not show up in an electoral cycle.

Tax cuts can’t compensate or replace structural change

The idea that lower taxes boost growth has a lot of merit on the surface because, if taxes are too high, they’re a disincentive to innovate, invest and work. But the evidence that simply lowering taxes boosts growth if you are a developed economy with a wide range of spending commitments that saves people money because the state provides schooling, health care, roads, and other infrastructure is not just unproven but unlikely. In other words, economies in Europe and elsewhere with higher taxes than the UK grow more quickly.

The UK’s overall tax structure is not too high and aligned with the average for OECD or G7 countries. Moreover, it is one of the most deregulated economies regarding labour market flexibility, i.e., protections. But it stands out as the lowest for research and development spending and public sector investment, especially since 2008, at just 0.7% of GDP compared with an OCED average of 2.4%. This means more R&D is required, not more deregulation.

The slow and lacklustre economic growth rate seems to be a function of these structural issues, not demand. Indeed, an ever-widening current deficit suggests that demand is the least of the UK’s problems. Instead, it is meeting this demand through domestic production. It is these factors that seem to be keeping productivity growth weak. Growth in the labour force is insufficient to offset this slowdown in productivity; therefore, overall economic growth has stuttered.

Incentivising the supply side is required to boost the UK’s long-term growth. Not enough of this was done in the Budget – however one may hope otherwise, otherwise the chances of its success are not favourable.