Following on from my last blog, which reviewed the history of poor fiscal forecasting in the UK and considered whether this was due to an overestimation of growth, or receipts, or an underestimation of spending or, indeed, all three, this blog looks at the effects of this persistent misstep.

Political optimism vs Economic facts: The Chancellor’s Role

While the OBR is formally independent, Chancellors continue to play a central role in shaping fiscal narratives. Forecasts are used to justify tax cuts, spending increases, or budgetary tightening. Optimistic projections allow Chancellors to present balanced budgets or meet fiscal rules – at least on paper.

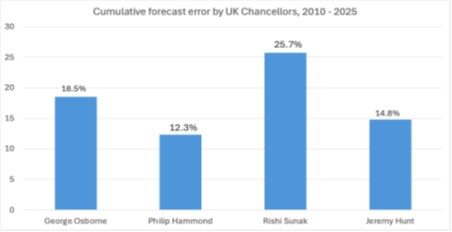

A comparative analysis of forecast error margins under different Chancellors reveals a pattern. George Osborne’s tenure saw cumulative forecast errors of 18.5%, driven by overestimates of growth and underestimates of borrowing. Philip Hammond’s more cautious approach reduced the margin to 12.3%. Rishi Sunak, navigating the Pandemic, faced a staggering 25.7% error rate. Jeremy Hunt’s early tenure saw a 14.8% deviation from forecasted outcomes. It’s too soon to compare Rachel Reeves’ tenure in the job, but early indications are that it’s not looking good.

These figures underscore a systemic issue: fiscal policy is built on projections that routinely miss the mark. The result is a credibility gap that undermines both political messaging and economic strategy.

Why Forecast Errors Matter for financial markets

Forecasting errors are not just academic exercises – they have immediate and tangible impacts on the real world. When growth is overestimated, tax revenues fall short and borrowing rises unexpectedly. When spending is underestimated, public services face shortfalls, necessitating emergency funding. These dynamics not only erode trust in fiscal management but also complicate long-term planning, highlighting the urgent need for reform.

For investors, forecast errors signal risk. Gilt markets respond not just to deficits, but to the perceived competence of fiscal governance. A country that repeatedly misses its own targets is seen as fiscally unreliable, which can raise borrowing costs and reduce policy flexibility.

Politically, forecast errors fuel cynicism. Promises made based on optimistic projections – balanced budgets, tax cuts, spending boosts – unravel. The public sees reversals, U-turns, and emergency measures, but rarely the underlying cause: flawed forecasts and a political narrative that keeps moving the goalposts.

Reforming the Budget Process

To restore credibility, the UK must reform its forecasting framework. Several options merit consideration:

- Dynamic Forecasting Models: Incorporate real-time data and adaptive algorithms to update projections as conditions change.

- Forecast Error Audits: publish retrospective evaluations of forecast accuracy alongside each Budget, highlighting deviations and lessons learned.

- Dual-Track Planning: develop both baseline and risk-adjusted fiscal scenarios, allowing for more resilient policymaking.

Conclusion

These reforms would not eliminate uncertainty – nothing will – but they would explicitly acknowledge it in the forecast process, allowing the UK to rebuild trust in financial markets regarding its handling of the UK’s fiscal position. The importance of this trust cannot be overstated, as it underpins so many economic decisions and market interactions. However, the consequences of inaction are dire. Persistent, directional errors in forecasting point to deeper flaws in how assumptions are formed, how incentives are structured, and accountability for those errors.

If the UK is to navigate future fiscal shocks more smoothly and with less volatility, it must move beyond cosmetic reforms and confront the systemic biases embedded in its forecasting machinery. Only then can credibility be restored to the fiscal projections on which so many economic decisions depend. That would lower borrowing costs not just for government but also for businesses and households across the country.