This was not a Budget that will live long in the memory, or the history books. Other than, of course, that under this government and Chancellor, it will be the last spring Budget. Recall though that Norman Lamont also decided to do something similar about twenty years but it never happened – because he got sacked. Assuming that it does not happen to this Chancellor, the real action will be in the autumn of each year, as is the case in many other countries. In spring 2018, there will be a brief summary statement of where the Budget position is relative to plan.

Phillip Hammond lived up to his sobriquet: ‘spreadsheet Phil’. Although there were lots of jokes, little in the way of new policy proposals were made and there was no big ‘vision’ at the heart of the Budget. Maybe this was deliberate on the Chancellor’s part.

He could be well aware that Budget decisions do not decide the path that the economy takes in the medium term. Much more important are trends in global oil prices, or what its key trading partners are doing or on decisions made by the US central Bank. It is clear that what Trump’s America does in terms of its relationship with Russia or NATO, or protectionism will have huge ramifications for the UK economy. Also, if there is a crisis Europe – our biggest trading area – the UK economy will be severely affected, and the Chancellor can only react.

There were of course important fiscal changes in terms of their impact on the sectors or individual affected – higher taxes for the self employed, for instance, did not go down well and could have broken a manifesto pledge not to increase National Insurance contributions. I have listed all of the main changes in the table below. Overall, though the changes were quite small. One estimate is that there were 28 new measures this year, compared with 77 in the last Budget.

The economic forecasts were adjusted and public sector borrowing and debt projections were pushed out one year, and updated. These figures themselves tell a big story about the accuracy and usefulness of such a detailed level of forecasting. Comparing the forecasts made this year and those made last year by George Osborne, shows a markedly different picture. Despite the Brexit vote, the 2016 economic growth forecast of 2% made by George Osborne last year was close to the actual outturn of 1.8%. For this year, he predicted 2.2% versus a projection by Hammond for 2%, again close. Of course, one could make the point that, if you cannot forecast growth for the year ahead with some degree of accuracy, then what’s the point of the exercise?

Further out, however, the GDP forecasts made by Mr. Osborne currently seem hopelessly optimistic. Out by 31% for 2018 (2.1% versus 1.6% by Hammond in the 2017 Budget) and 24% out for 2019 (2.1% versus 1.7%). True, the table shows that the economic forecasts converge by 2020 but who knows what will happen by then? The clear lesson is that economic forecasts are easily blown off course by events and even one year ahead can have significant variations.

Consumer spending has grown more quickly than expected but business investment is faring quite badly. This has implications for productivity and long-term growth, wage levels and ultimately tax receipts and the ability of the government to spend. Inflation is higher than predicted not just because of the impact of Brexit on the currency, which was declining anyway, but perhaps a combination of the UK’s persistent current account deficit and poor productivity.

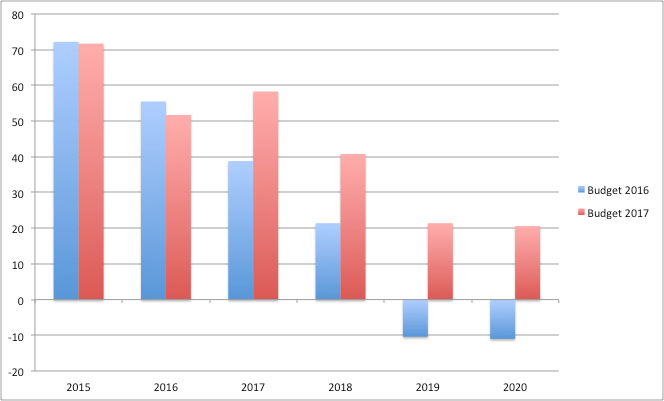

More importantly, these economic assumptions have a very outsized impact on government debt and borrowing figures – owing to cumulative effects and size of the debt numbers. Charts 1 and 2 show that government debt and borrowing are much higher in Chancellor Phillip Hammond’s Budget projections for the period ahead than those made last year by George Osborne.

Instead of a budget surplus of £11bn by 2020, there is instead borrowing of £21bn, a £30bn difference. This difference shows up more starkly in the debt figures – as it cumulates over the period to 2020. Debt this year – 2016/17 – is already running at £1.73trn rather than the £1.64trn Osborne expected just a year ago.

Instead of declining in 2018/19, and peaking at around £1.7trn, net public sector debt rises to £1.9trn by 2020, some £164bn more than expected in last year’s Budget. These are large numbers, some 8% of UK GDP in 2020.

The Budget was notable for one very big omission: it barely mentioned Brexit. One presumes that this was deliberate as its effects are not clear until the contours of the deal are more apparent. Yet some assumptions could have been made, around a smaller inflow of migrants and the economic impact that this could have on tax revenues and economic growth. What about the payments to Brussels: a request for £60bn for the EU as a divorce settlement is already well flagged. Where will that come from, if not from borrowing?

Assumptions in Budgets need to show less certainty and more uncertainty, with bigger margins of error and less in the way of spurious accuracy. The real world is not like the path shown in these projections.

Summary table and charts of key Economic and Fiscal decisions in Budget 2017

Table 1: Economic assumptions in two Budgets compared

Chart 1: Public sector borrowing higher under Hammond…

Chart 2: Public sector debt is therefore higher as well

Main Budget changes – spring 2017

Economics, public spending and politics

-

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) now forecasts growth of two per cent in 2017, up sharply from its previous prediction of 1.4 per cent.

-

However, growth was revised down to 1.6 per cent for 2018-19, then 1.7 per cent in 2019-2020 and 1.9 per cent in 2020-21. The forecast remained unchanged at two per cent for 2021-22.

-

By comparison, last November’s forecasts for the economy were 1.8 per cent in 2018-19, 2.1 per cent in 2019-20 and 2.1 per cent in 2020-21.

-

With GDP growth of 1.8 per cent in 2016, the UK was the second-fastest growing economy in the G7, lagging only behind Germany.

-

Inflation forecast to rise to 2.4 per cent in 2017 and 2.3 per cent in 2018, although it is also predicted to fall back to two per cent in 2019.

-

Borrowing is now predicted to be £16.4bn lower than forecast for 2016-17 at £51.7bn. Borrowing forecast at £58.3bn for 2017-18 and then to fall to £16.8bn by 2021-22.

-

Public sector net borrowing predicted to drop from the estimated 3.8 per cent of GDP for 2015-16 to 2.6 per cent for 2016-17, and then to 0.7 per cent in 2021-22.

-

Public sector net debt forecast to rise to 86.6 per cent in 2016-17, but then will fall to 79.8 per cent in 2021-22.

-

Employment tipped to keep growing until 2021 to reach 32.5m, while 31.7m people were employed in 2016.

-

Wages predicted to grow three per cent this year, and then by three per cent in 2018-19, by 3.3 per cent in 2019-20, 3.7 per cent in 2020-21 and 3.9 per cent in 2021-22. However, these figures do not take inflation into account.

-

Business investment predicted to fall by 0.1 per cent this year, before bouncing back in 2018-19 to grow by 3.7 per cent. Investment growth will peak at 4.2 per cent in 2019-20, the year the UK leaves the EU.

Personal taxation and national insurance

-

Tax-free dividend allowance to be cut from £5,000 to £2,000 from April 2018.

-

Class 4 National Insurance Contributions rate for self-employed to increase by one per cent to 10 per cent from April 2018, then further increased by one per cent in 2019.

-

Class 2 National Insurance Contributions to be abolished from 2018. This was previously announced by Hammond’s predecessor George Osborne and is supposed to offset some of the changes to Class 4.

-

The government is also considering changes to the tax treatment of benefits in kind, accommodation benefits and employee expenses.

-

Start of quarterly tax reporting delayed by one year for the smallest of businesses until April 2019.

-

Personal allowance to be raised to £11,500 and higher rate tax threshold to be raised to £45,000 this year, as planned.

-

Savings and pensions

-

New National Savings & Investment bond, which was announced in last year’s Autumn Statement, will be launched in April, with a 2.2 per cent interest rate.

-

The Lifetime Isa is also due to launch next month.

-

No major changes to pensions.

Corporation tax

-

Rate of corporation tax to be cut to 19 per cent in April and then to 17 per cent in 2020, as was announced at the Autumn Statement.

-

The government plans to rework some of the red tape associated with research and development tax credits.

Business rates

-

The chancellor did not go as far as abolishing business rates but did say the government would be consulting on the controversial issue ahead of the next reevaluation.

-

£435m set aside to help businesses cope with rising rates, including a £300m hardship fund to be set up to target individual cases of those badly affected.

-

Any business coming out of small business rate relief will benefit from an additional £600 annual cap, so no business’ bill will increase next year by more than £50 a month.

-

Pubs with a rateable value of less than £100,000, which is 90 per cent of all pubs, will be given a £1,000 discount on business rates.

Vices

-

No changes made to alcohol duty or tobacco duty, with rates increasing by RPI inflation for the former and by RPI plus two per cent for the latter.

-

Minimum excise tax (MET) duty for cigarettes set at £7.35 packet price.

-

Chancellor revealed sugar tax is raking in less than the government had hoped for, as drinks makers are already starting to reduce levels of the sweet stuff in their products.

Work and working families

-

£5m in returnship funding promised to help people return to work after a career break.

-

The government will soon start rolling out tax-free childcare for working families with kids under the age of 12, providing up to £2,000 a year per child.

-

Free childcare offer to double in September from 15 to 30 hours a week for working families in England with children aged three and four, up to a total value of £5,000 per child.

-

The government will also consult in the summer over parental leave for the self-employed.

Education

-

T-levels, a technical-skilled focused alternative to A-levels, officially announced.

-

Number of hours of training for students on technical routes aged between 16 and 19 to be raised by more than 50 per cent.

-

£320m to fund new free schools and £216m to invest in school maintenance announced.

-

Free transport scheme for children from poorer families to go to selective schools revealed.

Science, technology and innovation

-

Support announced for 1,000 PhD places, particularly for those studying science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects, which is an investment with a price tag of £90m.

-

£270m set aside to help with development of so-called disruptive tech, such as biotech, robotic systems and driverless cars.

-

£16m for a new 5G mobile technology hub and a £200m fund for superfast broadband.

Transport

-

Local authorities encouraged to tackle urban congestion with a £690m fund to be competitively allocated.

-

£220m to be invested to tackle pinch points on national road networks, including £90m for the North and £23m for the midlands.

Health and social care

-

An additional £2bn earmarked for adult social care spending over the next three years.

-

£425m for investment in the NHS over the next three years. This includes £100m to go towards accident and emergency departments in 2017-18 to help them prepare for winter and provide more on-site GP facilities.

Consumer protection

-

The government is to consider closely ways it can better protect consumers, such as stopping customers from being charged unexpectedly when subscriptions run their course and fining companies which mistreat and mislead consumers.

Financial services

-

The government confirmed it is on track with a total sell off of its stake in Lloyds, while the Bradford & Bingley sale process of £15.65bn of mortgage assets is expected to be done by the end of 2017-18.

-

On RBS, it said it would “continue to seek opportunities for disposals, but the need to resolve legacy issues makes it uncertain as to when these will occur”.

-

No new hike announced for insurance premiums tax, but the rate is due to rise from 10 per cent to 12 per cent in June.

-

No new rate changes announced for either the bank levy or the bank corporation tax surcharge.

Oil and gas

-

Chancellor revealed a panel of industry experts is to be established to mull how tax can assist sales of North Sea oil and gas fields, with a report of the findings due at the Autumn Budget.

Tax avoidance

- New penalties for enablers, such as tax advisers, of tax avoidance schemes which are later defeated by HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) are coming in. This was originally announced in last year’s Autumn Statement.