An intensely political budget

This Budget had many seminal moments worth mentioning. First amongst them is the signal it sent about the change in the Conservative party. Of course, it was intensely political, stealing economic and social policies from its main opposition. Agreeing with many government policies has left the opposition with little room to manoeuvre or disagree or create opportunities to differentiate themselves from the Conservatives. There was certainly little in this Budget for them to disagree with, except perhaps to say they would have gone further.

But this Budget was much more than that. It signalled the end of the Conservative party of Margaret Thatcher; tax-cutting, small government, less red tape, globally open, driven by the needs of business to remain competitive. These factors seem to feature very little in this Budget.

With hindsight, perhaps the death knell of that sort of approach was the so-called austerity years after the 2008/9 financial crisis and the lack of success of those policies in renewing the UK economy. After all, productivity has barely risen since 2008/9. Perhaps even Brexit may be a part of this reaction. Despite the talk of using the opportunity to open up, deregulate and compete with Europe, the how of doing that seems a big challenge in practice. We now have a Johnsonian Conservative government, little related to the one led by Margaret Thatcher. This Budget was one that the Prime Minister wanted, and his Chancellor delivered it for him.

The fiscal arithmetic

The Budget raised taxes by £40 billion – by 2.7% of GDP – to 36.2%, and levels last seen at the start of the 1950s. The table above shows this was a policy choice and not forced on the government by the Pandemic crisis. Most of these measures were pre-announced. It includes freezing income tax thresholds, increases in corporation tax, the health and care levy, and hikes in National Insurance contributions. It is important to note that these tax increases were enacted in the March 2021 Budget when borrowing was expected to be much higher than currently due to the weak OBR growth forecast of 4% and an expected higher borrowing figure as a result.

In the event, the economy grew faster than expected (thanks to the vaccine rollout), tax revenues were higher than anticipated, and more optimistic OBR forecasts, with lower ‘scarring’ from Covid (worth some £20bn), meant that the government had an extra £35 billion or so available. It could have been used to cut borrowing further and perhaps reverse some of the tax rises. Instead, the government will spend the majority of the money.

On the spending side, every department will see some increase over the period ending in the tax year 2024/25. Compared with 1978-79, the only sector that has not seen a higher department increase is defence. This period is a valid comparison because it is the closest to the spending increases, we see over the next parliament. It is no wonder that taxes had to go up. This is not to say that some of the spending increases were not justified, of course, because some of these sectors had been starved of funds during the austerity period, like justice, social care, prison, local authorities. However, even these increases leave some departments spending less than the amounts available to them, in real terms, before the financial crisis of 2008 and Osbornes’ austerity measures.

grWith an ageing population, alongside some freezing of council tax and grants, the pressure on local authorities will remain intense. As the IFS states, education spending has not fared well in the austerity period: “per-pupil spending in schools will have returned to 2010 levels by 2024…a spending per student in FE and sixth form colleges will remain well below 2010 levels.”

So, what happens to the net debt?

Because of more vigorous growth, net debt does fall but remains close to 100% of GDP and is well above the March 2020 forecast. The outstanding stock of debt will continue to rise – as the budget deficit persists for the entire forecast period – albeit on these forecasts not as fast as GDP growth. By the end of 2023/24, it will be £2.6trn, up from £2.1 trn in the fiscal year 2020/21.

Economic projections

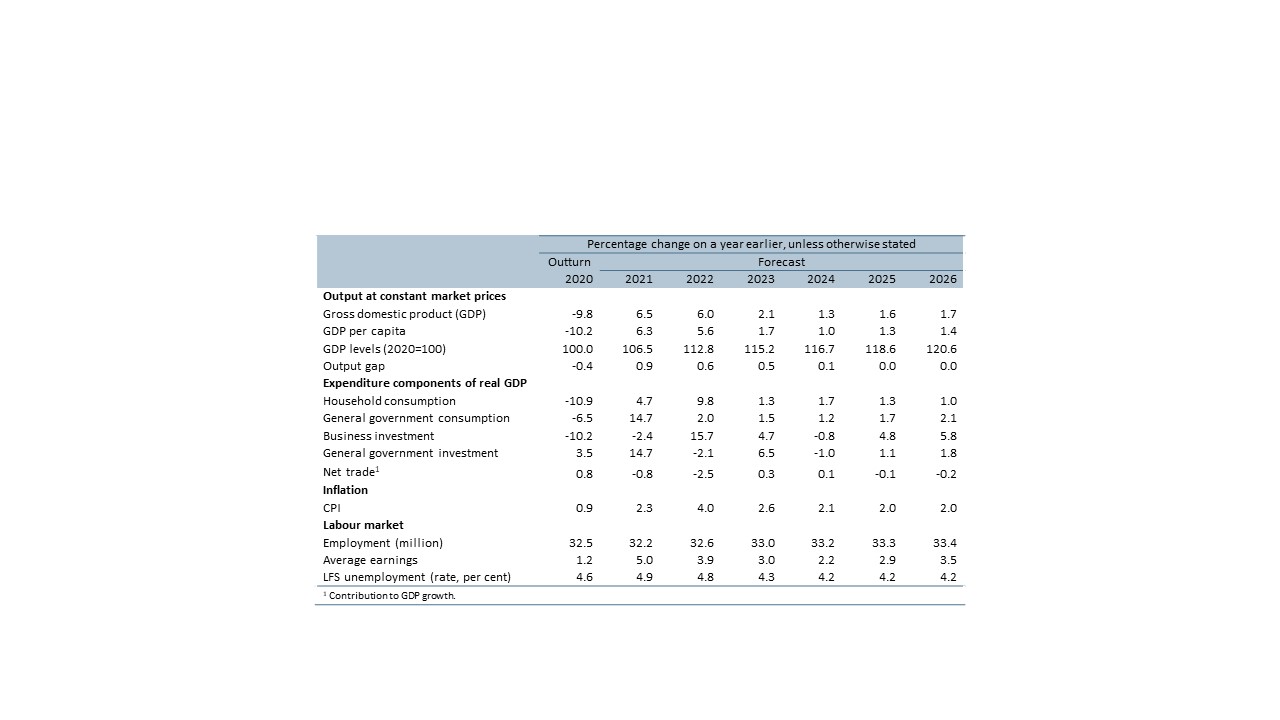

Faster economic growth, driven by high productivity, despite an ageing population, would be the answer to many of the UK’s challenges highlighted above. However, there seems little prospect of this based on the forecasts from the OBR. What is notable is that after growing a cumulative 12 ½% by the end of 2022 –so fully accounting for the near 10% drop in GDP last year – UK growth slows back to around 1¼% to 1½% from 2023. That reflects the small impact from levelling up, rather than a faster productivity growth rate.

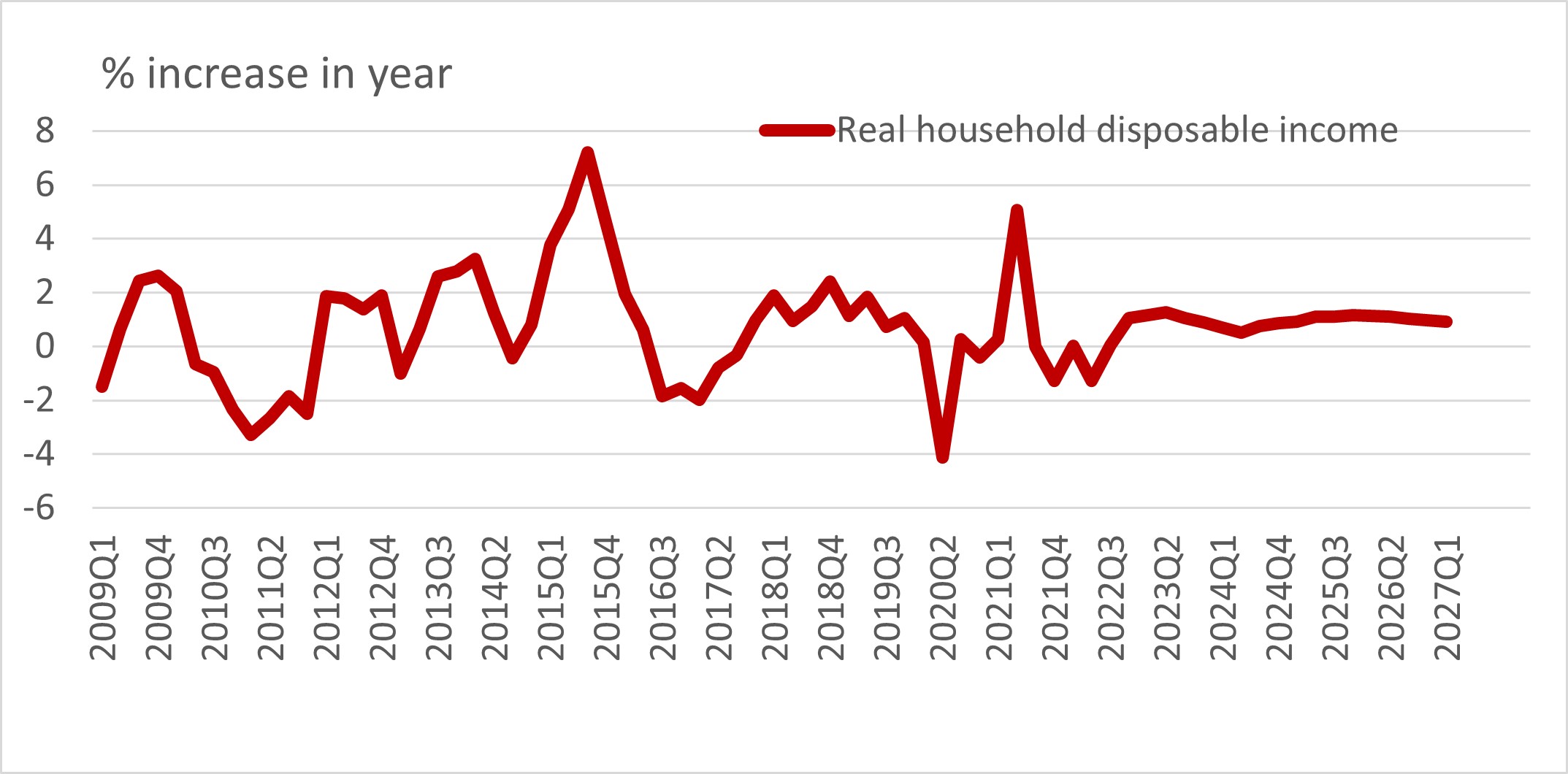

But it explains why living standards remain under pressure from higher inflation and from slowing wage growth (see chart 3).

Labour productivity growth has spent more time falling than rising in the period since 2008. The chart below (4) clearly shows how productivity and economic development are inextricably linked.

It’s also quite interesting that in the budget report, the government’s analysis (box 1. C, page 20) suggests that educational attainment and skills (human capital) are more important for driving productivity and regional performance than any other factor, including infrastructure. So, it seems odd that the focus isn’t more on boosting skills, education levels, NVQ, attainment and so forth than on the latter.

OBR forecasts suggest that the first rise in the UK Bank rate since they were cut to 0.1% in March 2020 may not occur until Q1 2022, making February 2022 more likely than November 2021.

The conclusion is that nothing the Chancellor has done will change the course of the economy in the next few years – Budgets rarely do – and the announced changes will not impact the trend rate of growth. What will determine whether he can cut taxes ahead of the next General Election is whether productivity picks up and inflation falls back, so that there is a benign environment where tax cuts can be afforded. But equally the economy could be blown off course by some of the issues he did not address, such as the costs of meeting net zero carbon emission pledges and the ever-rising costs of caring for an ageing population. After all, that is one reason why the share of government spending is rising as a share of GDP, and taxes along with it. If not for lower interest rates, and the attendant lower costs of funding the deficit, the challenge would be even greater and taxes even higher.