Optimism at the start of 2022 that, with the end of the pandemic, the UK was on the cusp of a period of robust and steady growth, was dashed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February. Although the headline average annual growth rate is 4%, it is highly misleading. The economy is in recession. Admittedly, economic growth is close to what was forecast by the Bank of England in November 2021, at 4% rather than 5%. However, growth could have been more balanced with all the increases in the first half and dropping off a cliff in the second half.

Official figures show that this started in Q3 and, on current trends, will undoubtedly continue into Q4. In fact, according to the latest Bank of England forecasts, the UK’s recession will last two years. Talk of a roaring 20s after the end of the pandemic now seemed like a distant dream. Instead, the UK faces years of stagnation. Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts published in November show the UK will not regain its 2019 level of GDP until 2025

A picture of weakening growth

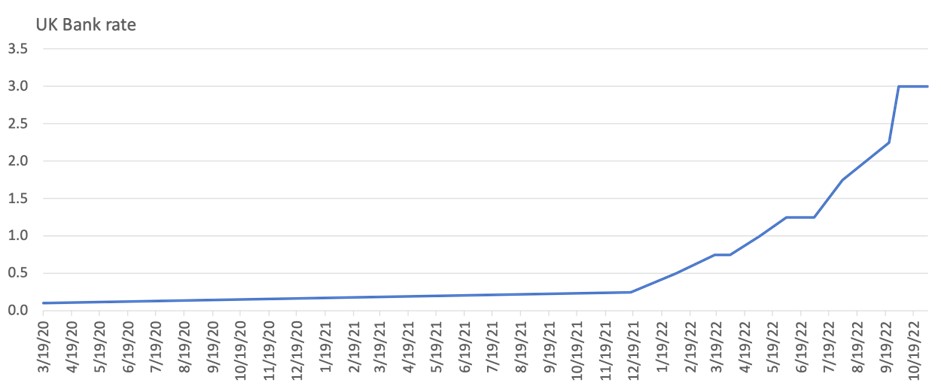

Three charts encapsulate what went wrong economically in 2022: higher inflation, sharply rising interest rates and weaker economic growth. Consumer price inflation is three times higher than was expected at the end of last year by the Bank of England – a 3.5% forecast against a peak of over 11%.

Chart 2: Interest rates response takes them to 14-year highs (Source: Bank of England)

The charts illustrate more than just the abrupt nature of the slowdown, they also show the devastating effect of inflation and the sharp rise in official interest rates on growth. High inflation reduces real spending power, creates investment uncertainty, and slows economic activity. The higher interest rates necessary to combat the corrosive effects of inflation increase the cost of borrowing, thereby reducing investment and consumer spending power because of higher debt servicing costs.

Global crisis compounded by domestic issues

On one level, it’s just another ‘Annus Horribilus’. Fate and circumstances out of the control of any government have led to this outcome. After all, every country has been buffeted by the global pandemic, the supply bottlenecks it created and then the massive global spike in energy and food prices from the invasion of Ukraine, a large food and agricultural fertilizer exporter by a large oil and energy producer. All that is, of course, true.

But the UK is more badly affected by these events than some of the other major economies. The OECD has put the UK at the bottom of its league table of G7 economies’ growth because it has yet to recover from the output loss suffered during the 2019 pandemic.

Political events had a significant influence in creating uncertainty in the UK in 2022. Three prime ministers (Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak), one of them the shortest serving in UK political history, five fiscal events, four chancellors of the exchequer (if Jeremy Hunt is counted twice because of being appointed by two different Prime Ministers). It is difficult to argue that this level of political turmoil has not contributed to creating economic uncertainty and weakening growth from volatile policy decision-making amidst the chopping and changing of priorities.

Public sector under pressure

The inconsistency of policies also contributed to the strikes that beset the public sector. But we should also be mindful that this is the long-run consequence of the policy of austerity, which was put in place after the 2008/9 global financial crisis and recession by then Chancellor Osborne, and not just a consequence of events in 2022.

It has resulted in public sector pay consistently being below that of the private sector and below that of consumer price inflation. That combination has resulted in real-time cuts in pay adjusted for inflation across whole swathes of public sector workers, compounded by the relatively weak UK economic performance since 2008/9.

In addition, the UK has an ageing population, which means demand for public services has increased faster than the ability of lacklustre economic growth to produce the tax revenue to meet this demand. The challenge of meeting this increased demand cuts across party politics, but it is a political issue. Under these circumstances, the strikes will likely continue into 2023 until a deal involves the government. However, this would unlikely manage the longer-term issue of how to fund the rising demand for public services in the country with an ageing population, slow growth, and stricter restrictions on inward migration.

A bright spot amidst the gloom

So, 2022 has not left the UK economy in great shape, and the next few years will undoubtedly be a struggle. But there was one bright spot amidst the gloom: the unemployment rate remained lower than expected. At 3.7%, the unemployment rate is below a year ago and below pre-pandemic levels. Meanwhile, the number of job vacancies (at 1.2 million) is above pre-pandemic levels. Indeed, job vacancies match those that are unemployed, meaning that the UK is entering a recession with full employment or one job to each vacancy. There are mismatches in skills, geography etc., so there is not a direct read across, but there are jobs. Filling these roles would unlock growth and productivity gains.

Post-Brexit, there have been issues recruiting people who from EU countries, particularly felt in sectors from hospitality to farming, and food manufacturing to warehousing. But there is also a rise in inactivity as more people over 50 retire and more seem to be suffering from long-term illness and are unable to work.

Fixing some of the problems identified could create growth opportunities.