As a wise sage once said: forecasting is very difficult, especially about the future. But maybe we can discern some trends that will at least help to determine the direction of the decade ahead, whilst acknowledging how little we can ever truly predict. Few people back in 2010, for instance, would have thought that in 2016 the UK would have a referendum on the EU and be leaving it by the start of the next decade!

A decade of change

What a transformation there has been since William Hague made opposition to the single currency the centrepiece of his election to be the leader of the Conservative party in 2001.

It is almost ironic that in 1973, another Conservative – Ted Heath – took the UK into the EU, a move ratified by an overwhelming majority of Tory MPs in 1975. In 1986, yet another Conservative –Margaret Thatcher – signed the Single European Act, creating the single market.

So, the economic and political implications of leaving the EU seem a good starting point for issues facing the UK in the decade ahead, as is the near certainty that the current government has a majority great enough to last its full 5-year term comfortably.

Demanding external focus

With some conviction, it seems, we can say that the UK is leaving the EU and its institutions. That may be this year, assuming no extension to the self-imposed 31 December 2020 departure date. In so doing, it is more likely than not that the UK will strike some sort of trade deal with the EU, in some form or another. It seems reasonable to argue that such a deal will more likely to only cover tariffs than retain single market access or any freedom of movement of goods, people, services or capital.

It would also seem sensible to assume that in the time allowed –12 months in theory, but in practise six months – it is highly unlikely that a comprehensive trade deal will be agreed. Therefore, a deal covering goods and security would be more likely than one covering digital, financial and other services. How difficult it will be to reach an agreement will no doubt become more evident in the months ahead.

The longer-term economic and political implications will surely take well into the 2020s to become apparent and for us to, perhaps, begin to judge whether it was all worth it or not and who the winners and losers are from the process. Replication of trade deals with the other 50 plus countries that the UK currently has via the EU – which will no longer apply once the country leaves the bloc – will presumably take up a big chunk of political time in the next decade.

Addressing the many domestic issues

That said, however vital the external relationships, the main economic focus of the government will, of course, be on the domestic issues facing the UK, of which there are many.

Not least is the abysmal state of UK productivity growth at the whole economy level. With no gains for a decade, productivity sits nearly 25% below where its previous trend up to the financial crisis suggests it should be. This issue lies at the core of why there has been little gain in real pay in the UK over the last ten years. It also has a regional bias, with productivity in London and the south-east some 30% higher than in the rest of the country. And that’s on average; the disparity is even wider if we compare the worst performing areas of the country with the best performing.

The effects of these differences are pernicious and play into different standards of living across the country and are unsurprisingly reflected in feelings of being left behind and not valued. Moreover, slower growth in earnings stemming from weak productivity reduces the tax revenues required by government to help deal with the effects of an ageing population on social care and health spending.

Sluggish economic activity characterises the decade

Long-run data from the Bank of England shows that in the decade to 2020, real pay growth was zero, compared with an average increase in the last 70 years of 2.2%. In a research paper published in 2018, the Bank said that the growth of real (inflation-adjusted) wages was the weakest since records began in Napoleonic times.

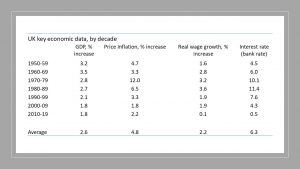

Other UK economic data for the decade to 2019 highlight how unusual it was compared with the previous 70 years. Economic growth in the UK has averaged just 1.8% in the last 20 years, after recording 3% in the decade to 1999. Price inflation averaged 2.2% in the previous decade, against a 70 year average of 4.8%. With weak economic growth and such low price and wage increases, the Bank of England’s base rate has averaged just 0.5% in the last decade, the lowest rate in the 326-year history of the Bank and nearly 13 times lower than the 70-year average of 6.3%. But this has not kick-started economic activity, even with bank rate below the rate of GDP growth and well in negative territory when adjusted for price inflation in the decade. So, something is going on that suggests the usual policy levers are not working.

Deep impact of crisis

It is instructive that the main economic impact on the first two decades of the 21st century was not the effect of the war in the Gulf following the attack on the twin towers in 2001, but the aftermath of the global financial crisis and recession in 2007/8.

The crisis itself, the policy measures taken to deal with it and their consequences on wage growth, on asset prices, on perceptions of winners and losers, on wealth and income inequalities, seems to have sapped popular support for politicians and policymakers. It’s no surprise that Labour lost office in 2009. What may be more surprising is that the party continues to fail, despite being out of office since 2009 and a decade of austerity measures by its replacement. But one thing did not change: the decade to 2019 started with an Etonian as Prime Minister and has ended with one as Prime Minister.

Bumpy times ahead

In the UK, it appears that there has been a loss of confidence – not in the market economy per se in my view, nor in established parties, as support for the Conservatives shows – but in the political solutions that some offer voters.

In this context, it is undoubtedly not a shock that fractious politics persisted for nearly all of the last decade. But the impasse was broken in the last month of the previous decade with the UK’s ‘first past the post’ electoral system delivering the largest majority to the Conservatives since 1987, 56% of the seats in Parliament. But on a vote share of around 44% of those that voted.

This is how the 2020s is starting: big public sector decisions for spending on infrastructure, on health and social care are looming, multiple trade deals (at least 55) need to be negotiated. Meanwhile, significant global demographic shifts are underway, climate change may be reaching an inflexion point, and technological change is occurring at a dizzying pace across a greater range of sectors than ever before in human history. Opportunities abound from meeting all these challenges, so hold on tight; it could be a bumpy ride through the 2020s. Will it be as eventful as the ‘roaring twenties’ of 20th century folklore?