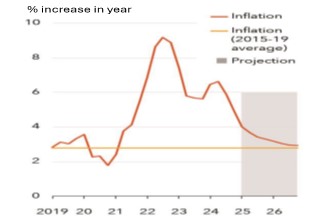

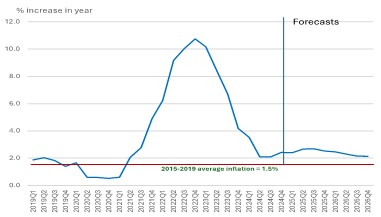

In recent months, official interest rates have been cut worldwide as inflation has fallen sharply from the peak of over 9% following the end of the Pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which drove up global food and energy prices, see chart 1. Global price inflation has fallen to the rates before the Pandemic and Russia’s invasion. UK consumer price inflation followed a similar trend, as shown in chart 2 – falling close to the inflation target of 2% and back to a similar rate increase recorded between 2015 and 2019, i.e., before the Pandemic and the Russian invasion.

However, the economic effects of high inflation and still high interest rates are being felt, with unemployment up, job vacancies falling, retail sales falling, and growth flat. Economic recovery is fragile as the MPC meets next week – 5/6 February 2025 – to deliberate on whether to cut interest rates. Moreover, although it has lowered interest rates, it has not reduced them as much as most peer countries.

Over the coming two years, the financial market expects the UK central bank to cut the Bank rate to around 4%. These rates are well above the 2015 to 2019 pre-pandemic levels – when they averaged 0.5% – and from 2008 to 2024, when they averaged 1.3%. However, it’s unlikely that bank rates can return to those lows, not least because of the end of the historically low consumer price inflation caused by the Pandemic and the surge in oil, gas, and agricultural prices due to the events in Ukraine.

At the same time, the inflation surge appears to be over, and UK consumer price inflation is expected to hover around the central bank’s inflation target for the next few years. This alignment with pre-pandemic levels signals a stabilisation, offering an environment for reducing interest rates. There is potential for the UK bank rate to return to a new norm, a balance between the exceptionally low rates of 2008-2019 and the 20-year average from 1980-2008 of 9.6%. This new norm would account for real GDP growth of 1 to 1½% a year and inflation of 2%, implying an average nominal bank rate of 3 to 3.5% when combined.

When thinking about interest rates, it’s crucial to consider the ‘real’ rate of return to investors, which is the bank rate adjusted for the inflation rate. The long history of interest rate data and economic theory suggests investors want a return above the rate of consumer price inflation for lending money, to account for the risk of not getting their money back, and to maintain their purchasing power (getting the same quantity of goods or services back in future).

However, the UK’s bank rate adjusted for price inflation has averaged minus 1.7% since 2008. The negative return is due to low interest rates and higher inflation rates. For long-term mortgage loans, the real rate has been plus 0.2%. New Bank of England calculations suggest that the ‘real’ average loan rate for the economy is now about 0.7% to 1% if we assume that consumer inflation hits the target of 2%. That, in turn, implies a new normal for the bank rate of 3%, including inflation, when the economy is growing at its full potential of 1 to 1½% pa.

Some private sector forecasters predict this will occur in 2025, but the market consensus is currently at 4% for the low of bank rate in the medium term. That still seems too high for an economy with low price inflation that’s struggling to grow and compared with the last decade.

UK inflation will be close to target in 2025

UK consumer price inflation is forecasted by the Bank of England to drop close to its 2015-2019 average by Q2 2025 (see chart 2) and meet the 2% target by 2026. Updated projections from the MPC are due on 5 February but likely won’t differ much from the previous ones.

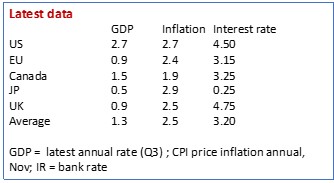

Comparing the UK’s GDP, inflation, and interest rates with its four key trading partners – the US, EU, Canada, and Japan – shows an interesting divergence in their policy stance (see Table 1).

The UK central bank is slower to cut interest rates compared to its peers, despite its inflation now matching the G7 average.

Japanese interest rates are the lowest, due to high household savings. Canada and the EU match the 3.2% average interest rate, while the UK and US exceed it at 4.75% and 4.5%. UK rates are 1.5 percentage points above the average despite its 2.5% inflation matching the group average.

US interest rates are also above the group average by 1%. However, that can be justified by looking at its annual average GDP growth of 2.7% in Q3 2024, which is also well above the average of 1.3% (see Table 1). That means it needs a tighter policy stance than the other economies to keep a lid on its inflation, which is just above the group average at 2.7%.

However, the UK’s GDP growth in Q3 was just 0.9%, a figure that is cause for concern as it is well below the group average of 1.3% and significantly lower than the US’s 2.7%. This disparity raises urgent policy issues that must be addressed.

Scope for rate cuts

The UK’s tight monetary policy stance, as indicated by the gap between its rate and the average in the table, raises serious questions. Is the Bank of England keeping interest rates higher than they should, potentially damaging the economic recovery for no gain in lower inflation? This approach could be a deterrent to investment, as it raises firms’ hurdle rate for investing and discourages consumer borrowing, thereby weakening the economic recovery.

The UK’s economic landscape presents a unique opportunity for interest rate adjustments.

Given its starting point of having the highest interest rate in the group shown in the table, the UK has the most potential of any G5 member to cut interest rates in the year ahead. Therefore, to help boost economic growth, the MPC should cut interest rates to the average of 3.2%, as shown in the table, as quickly as possible while signalling its intent to avoid market turmoil.

Summary

Maintaining high interest rates – when not justified by high inflation – harms business investment, growth, consumer expenditure, and the broader economy. Lower interest rates mean lower mortgage costs, increased housing market activity, a slower rental value increase, and increased affordability. For the government, it means a greater likelihood of achieving the target of building 1.5 million homes over this parliament. Lower interest rates would make it easier for housebuilders to meet their hurdle rate of investment, leading to an increase in the number of projects and the delivery of more homes at lower prices to buyers.