With negative rates in Europe (the ECB deposit rate is -0.5% though the lending rate is zero), Switzerland and Japan, how low can rates go in the UK? The answer is that they can go lower, which means negative. The Bank of England is currently studying how that would work in practice, with the Governor keen to emphasise that this is not a sign that they are preparing for such a scenario.

As UK annual price inflation sits well below 2% and looks likely to remain that way for the next year or so, inflation will not be an impediment to negative interest rates. In August 2020, for instance, annual consumer price inflation was just 0.2%. What’s more, most estimates assume that the economy will not make up for the output loss owing to the Pandemic until 2024. So, as chart A shows, there should be little inflation pressure from excessive growth relative to the capacity to meet demand over the next two years, at least.

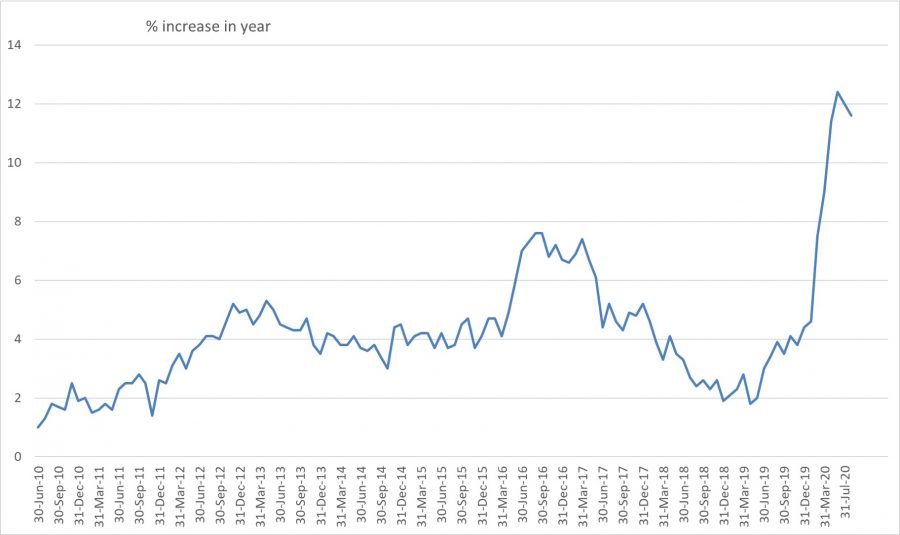

However, one reason why the Bank might be cautious is that money supply growth has rocketed in the last few months, as we can see from chart B.

What it means for UK savers

But low-interest rates have consequences for savers. The combination of an ageing population and low savings rates will mean that people will have to retire later or retire poor. Indeed, to keep pension and retirement systems viable in an age of negative or low real interest rates, the government may have to extend the retirement age and increase the amount that people pay in. Otherwise, it will mean many poor pensioners who will have to be supported by other government spending measures such as social security.

With record low-interest rates prevalent everywhere what are savers to do? They could take more risk and invest in assets with higher returns, but clearly this brings with it a higher risk of loss too and is not usually a risk that people close to retirement want to take.

Investors invest and savers save

Although evidence from recent years suggests that more than half of the population live from pay cheque to pay cheque, suggests a lack of ability to save for a significant number of people, for those than can save, we can see from recent data that they seem to be doing just that. Recent evidence is that households are saving more out of aggregate income, meaning a sharp rise in the savings ratio.

It’s a similar picture if we look at investments; those who can continue to invest are doing so as we can see from rising asset prices, the fall in bond yields and higher commercial and residential property prices over the last few years. One adverse side effect of this is a widening of the wealth gap. The reason: those reliant on income rather than capital will see a reduction in relative wealth, especially having seen no rise over a decade in average real pay levels.

Private sector struggles but government spending boost

And it’s not just savers that feel the effect. Zero or negative rates depress bank profits, making them less likely to lend. They allow ‘zombie firms’ or companies that would fail if interest rates were not covering their interest costs to survive and so sap the profitability of more productive firms. Furthermore, pension funds and insurance companies can struggle to meet their long-term liabilities when returns from bonds are low or negative, see Charts C and D.

But there is a silver lining. Low long-term interest rates allow government spending to be higher for longer than it would be otherwise, because the cost of funding the deficit is cheaper the lower long-term interest rates are. Real government bond yields – adjusted for price inflation – are, moreover, well into negative territory. Hence, the government should focus on financing the fiscal deficit at points in the gilt curve that is further out and closest to zero in nominal terms, meaning they are being paid to borrow when coupon payments are excluded.