The new Prime Minister has taken office during a historic economic, political, and social crisis for the UK and world economies. Just days ago, Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, shut down the Nord Stream One pipeline carrying gas to Germany – and said that the pipeline would not be reopened until sanctions against Russia are removed. Since that is highly unlikely while the war is going on, the knock-on effects of high energy prices and perhaps an increase in them over the winter – depending on how severe it is – will persist over the next few years.

To give some further context, three overarching crises face the world economy:

– the lingering effects of the supply chain disruption created by the pandemic

– the Russian invasion of Ukraine has disrupted food and energy supplies to the world

– the use of energy as a weapon of war by Russia.

UK feels the effects

The UK economy has barely recovered from the downturn created by the pandemic – it just about reached its 2019 pre-pandemic peak in Q1 of 2022 – but the Bank of England is already forecasting that there will be another recession. It predicts that it will last for five quarters, beginning from Q4 of this year with a drop of 2% in GDP over the period. In other words, after the pandemic of 2019, the UK economy will be smaller in 2024 – and perhaps 2025 – than in 2020. By any measure, that implies a substantial social, political, and economic shock.

It will undeniably leave people poorer on average than they would otherwise have been. Taking the annual average long-term growth rate of 2¼% pa implies that in 2024, the UK economy will be ten percentage points smaller than it otherwise would have been, and this loss of GDP is around £224bn.

PM under pressure

All this at a time when it has an ageing population with attendant pressures on care and NHS spending required to look after that ageing population. Even if the calculations are imprecise, there’s no question that the UK will lose approximately four to five years of output. And that is fuelling social, economic, and political pressure to do something about it.

No doubt, a political leader for these times will appear with a narrative and a message that offers optimism about the way forward. Time will tell whether the new Prime Minister is such a person. For now, though, let’s focus on the implications of the current energy crisis and what may happen over the year ahead.

The effects of rising energy prices

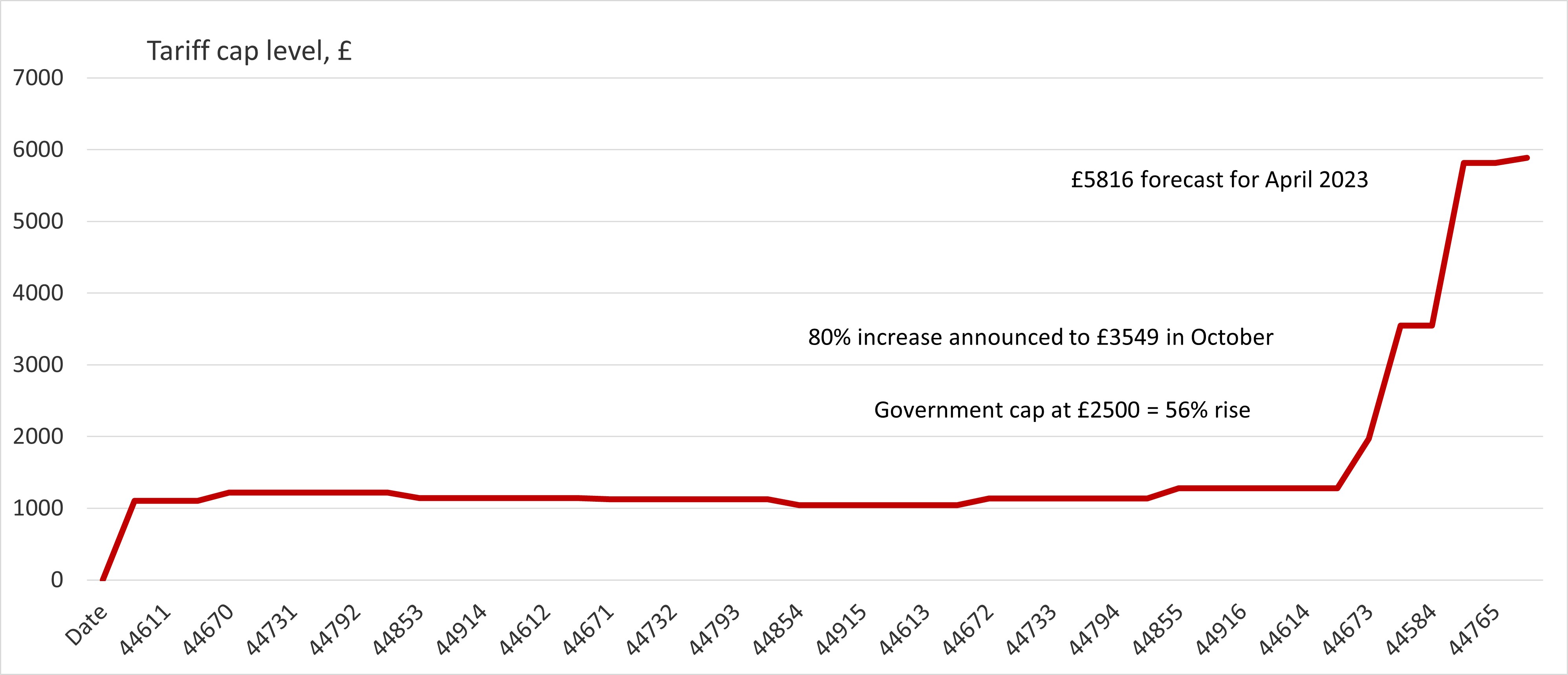

Rising energy prices have two effects on the economy: they raise price inflation across the board and reduce income for users, leaving them with less to spend on other goods and services. Hence, it’s a cost-of-living crisis, given the sheer scale of the hit to incomes from the increase in energy prices that has taken place and is likely to occur if no action is taken.

If the new Prime Minister allows the market economy to work, users will have to cut back on energy use by turning down thermostats, turning off lights, heating less water etc. A business could go to shorter working weeks and lay people off. So, subsidies will likely accompany efforts to boost supply, such as signing off on fracking, more wind farms and solar energy, and drilling in the North Sea.

But these are long-term solutions, not short-term fixes, and will do little to alleviate a winter crisis for UK households and businesses. Moreover, this occurs when the UK is more energy dependent on imports than it has been since the 1970s or before the North Sea oil boom.

Cushioning the blow?

So, along with every other major economy in Europe, it’s likely that the UK will have a price freeze. In other words, set a cap on the retail price of oil and gas combined and meet the difference between the retail price and the wholesale price via a subsidy of suppliers. For instance, Germany announced a £56 billion support package over the weekend for households. Since there is already a UK £40bn or £400 for every household support package due, any additional support announced in the next few days will be on top of that.

Hence, the total support package is estimated to be over £100bn. It is unlikely to be targeted at the poorest but, for simplicity, cover all users, which will mean some who can afford to pay will also get a subsidy, unlike, say, the furlough scheme where only those out of work got support, and that was capped at 80% of salary. Moreover, the final amount will depend on whether it’s for one year or two years and whether it includes just consumers or some businesses.

Balancing policy costs

Whatever the cost, it will be a significant increase in the stock of government debt. It may conflict with the Prime Minister’s other promises, such as cutting taxes, reversing national insurance increases and the corporation tax hike planned for 2025. All these will mean a higher level of debt and a significant increase in government borrowing unless funded.

Such an outcome could have enormous financial market implications, particularly if bond markets worry about how the government will find the money for tax cuts and public sector spending increases. However, despite public debate about these risks, there were plenty of bidders in the latest UK 10-year government bond auction. Moreover, the more fundamental point is that the pot of savings in the UK to fund more significant government deficits is likely to be greater in the next few years because of an ageing population and the consequent need that many will have to save for retirement.

These savings allow the government to run bigger deficits than they would otherwise and stave off a crisis for the pound sterling if external investors take fright at the prospect of increased borrowing. Or there could be a sharp dip in bond prices as investors demand higher yields to lend in a situation where government debt is rising. One economic risk is that public sector borrowing crowds out more productive private sector borrowing. Either way, it’s another sign that we live in unprecedented times and that the challenges for the new PM are many and multifaceted.

Creative solutions to these challenges are required but keeping financial markets on board will be crucial to avoiding a crisis in the pound or the bond markets. That may at least buy space and time to deal with voters’ concerns and expectations about other issues, including the NHS, housing, low productivity, falling real pay and weak economic growth. All of which are inextricably linked.