In recent weeks Bank of England officials have made comments which have garnered lots of attention. I want to focus on four of those because they show different aspects of the Bank of England’s views that economists usually debate without much public fanfare. But since they have gone public, it’s worth discussing them in this blog.

Two of them are exhortations from Governor Bailey to workers not to demand too much in the way of pay rises and to business owners to show restraint in meeting pay demands to help keep price inflation low.

Both are rather strange requests from the head of the Bank of England, charged with keeping inflation low and stable and who has been given a toolkit of measures to try and do so. On the one hand, it’s a clear sign that inflation is out of control, and the governor is desperate to try and enlist as much help as possible. Conversely, it could be a sign of desperation because inflation is seemingly coming down more slowly than they would like to see.

Worthy of correction

But two other officials from the Bank of England have also made some comments that are worth mentioning recently. One is Hugh Pill, the chief economist at the Bank of England, who commented that the UK should accept that it’s poorer, citing per capita data. Doing so would lead to less willingness to fight for a higher wage increase, which, if successful, would generate inflation because the economy is not producing the goods to meet the resultant demand. This comment merits challenge and some analysis.

The other is from the deputy governor of the Bank of England, Ben Broadbent. His comment is that money supply growth does not cause price inflation. Therefore, efforts by the Bank to reduce the money supply in the years before the Russian invasion of Ukraine would not have prevented the current price inflation we are seeing.

These are comments worthy of some discussion and analysis. There are two answers to these comments: theoretical and evidence-based – although the two are linked. The upshot is that the Bank of England needs to be corrected.

The theoretical argument is that wages are paid out of productivity, and in a market economy, wages (also a price, of course) do not cause consumer price inflation. It is possible in an economy where consumer wages are indexed, and prices rise in equal measure. That is not the case in the UK, and so it’s not a valid argument. Even if that were the case, the indexation of wages to prices would mean too much demand chasing too few goods as productive capacity is still limited. In that scenario, firms would cut output as they fire workers they cannot pay because there’s been no increase in their productivity.

The evidence shows that we can dismiss the view that wage inflation is causing price inflation by comparing wages adjusted for inflation with price inflation. UK wages rose by 6.6% in the three months to February, but annual consumer price inflation rose by 10.1% in the same period. On the official figures adjusted for various timing issues, this left real or inflation-adjusted wage inflation down 3% on the year.

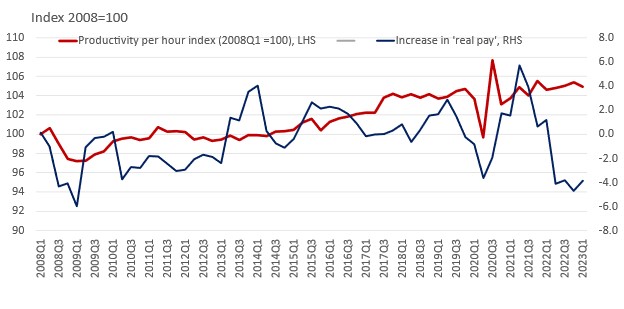

Indeed, real wages in the UK are about the same as where they were in 2008. The first chart shows that the UK has experienced average negative growth in real wages since 2008, mirroring its poor productivity.

In other words, UK wages have stayed the same over the last 15 years, proving that wage inflation is not the driver of price inflation.

The second chart illustrates that the surge in price inflation ahead of the Russian invasion of Ukraine was already underway because of an excess increase in money supply in the UK caused by having ultra-low interest rates for too long and quantitative easing, which pumped plentiful liquidity into an economy with unchanged productivity.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine amplified the effects of the rise in monetary growth. That may be why UK price inflation is higher than in Europe or the US.

In other words, the Bank of England has reasons to look back and wonder whether it could have done more to mitigate the extent to which inflation has risen and persisted in the UK. The increase in money supply was occurring at a time when there was no corresponding increase in either UK productivity or its output. Therefore, price inflation was inevitable, as chart 2 shows.

Belatedly, the Bank of England has been focused on reducing the money supply through quantitative tightening and raising interest rates. The risk is that by proving that they are now tough on inflation, they are overdoing it. The evidence of some contraction in the money supply and of too high interest rates is beginning to increase. It’s not that UK per capita GDP has fallen it’s simply that it has not risen much since 2008, in line with the weak productivity performance. Getting it right today is better than overdoing it to pay for the sins of the Bank’s past laxity.