Global financial markets are seeing the most significant banking market-driven turmoil since 2008/9, the first bank failures in the US since Washington Mutual in 2008 and a sharp fall in bank stocks. US monetary authorities reacted quickly, injecting liquidity, and guaranteeing deposits. But bank stocks around the world are generally lower than they were before the crisis, see chart 1. Currency, bond, and interest rate markets underwent extreme volatility as well. There was initially a flight to the dollar as fears about liquidity spread.

Does this event herald the start of a new phase of bank failures and a rerun of 2008, or is it a ‘storm in a teacup’ that will quickly blow over? The short answer is that it is not a rerun of 2008, and it will blow over. Still, it is a reminder of the centrality of finance in a modern economy, the risk of becoming complacent, and forgetting why regulators tightened rules after the last crisis. The good news is that those rules have worked.

The reasons for the failure of New York Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the US and Credit Suisse First Boston in Europe are unique to their circumstances and not a sign of a general malaise.

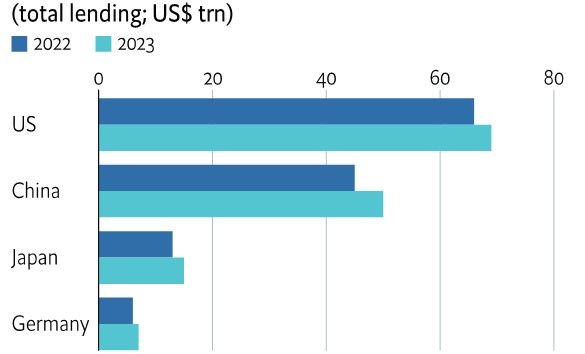

Capital ratios are much healthier across the world for major banks. Because of Basel III, capital ratios are roughly three times higher in Europe than in 2008. Bank liquidity ratios are similarly very high, and banks are more profitable now than before. So, an outright crisis or credit crunch is highly unlikely. However, there might be lower lending at the margin as spreads widen, with a potential impact on consumption and investment.

The current economic slowdown will mean corporate debt defaults will likely rise, albeit from shallow levels. But lending, deposits and profits are high and healthy at most banks worldwide, including those in the UK, which have faced a stringent regulatory environment since the last crisis, including ringfencing, see chart 2. Bank profitability has been boosted by the end of cheap money driven by the rise in inflation, which means that profit margins are naturally relatively healthy.

Silicon Valley Bank in the US failed because a rule change in 2018 meant that they didn’t have to report as much to the authorities about their liquidity position as previously, nor did they have to keep the same amount of capital against lending that they were doing, as more tightly regulated banks had to.

But the good news was that in the UK, because SVB’s entity was a subsidiary and not a branch, it was subject to the stricter UK rules (compared to those in the US), which meant that the Bank of England could act more independently to rescue it and force a sale. Moreover, Silicon Valley Bank in the UK was profitable compared with its parent in the US, making a net £88m profits in 2022.

What is clear is that even the current guardrails to prevent bank failures will not work during extreme market turmoil, as contagion can spread quickly. A bank can still be subject to a run on its deposits by its shareholders and investors if it runs into difficulty. The issue for regulators is to let a poorly managed firm fail without it affecting others. The latest events show that this conundrum still needs to be solved.

Recent events are also a reminder that banks and financial institutions play a utility-like role in providing what is now seen as essential services. Still, at the same time, they are privately managed with private profits driven by their activities. Yet, when they fail, the public purse is used to rescue them, meaning the profits are private, but the losses are socialised. That is the problem revealed by this crisis, as it was in 2008. That makes European banks in particular look cheap, see chart 3.

Unconditional support is politically and ethically unsustainable. Therefore, it’s clear that for institutions large or small that must be rescued by government guaranteeing depositors, they must have enough loss-absorbing equity, capital buffers and the liquidity available to ride out ‘normal’ shocks.

That means that tight supervision and oversight, which some argue is too rigid and overly bureaucratic, will continue. That pushes against what some of the UK’s political bias has been trying to achieve, for example, in the recent financial services and markets bill, to loosen the regulatory capital and ringfencing structures put in place after the financial crisis of 2008. That will now be much more difficult for the UK authorities to be able to do to distinguish the UK – post-Brexit – from its European counterparts.

Therefore, this crisis is not a rerun of 2008/9, but neither is it just a storm in a teacup.