Media Coverage May 2023:

As expected by financial markets, the Bank of England has raised interest rates by a quarter of one per cent to 4.5 per cent. At the same time, it upgraded its growth forecasts by the largest amount on record, from a recession to stability. This higher growth, combined with concern that inflation is not falling as quickly as food prices continue to rise, prompted the increase in interest rates. The danger now is that the Bank will find itself overcompensating. Growth in prices is already outstripping growth in incomes by around 4 per cent per year. Money supply growth is slowing fast and suggests that we could face deflation in just two years time. The Bank of England’s own forecasts show inflation well below its 2pc target by the end of the same time frame. Focusing today on the current backward-looking inflation rate risks missing the fact that rate rises take 2 years to have their full effect.

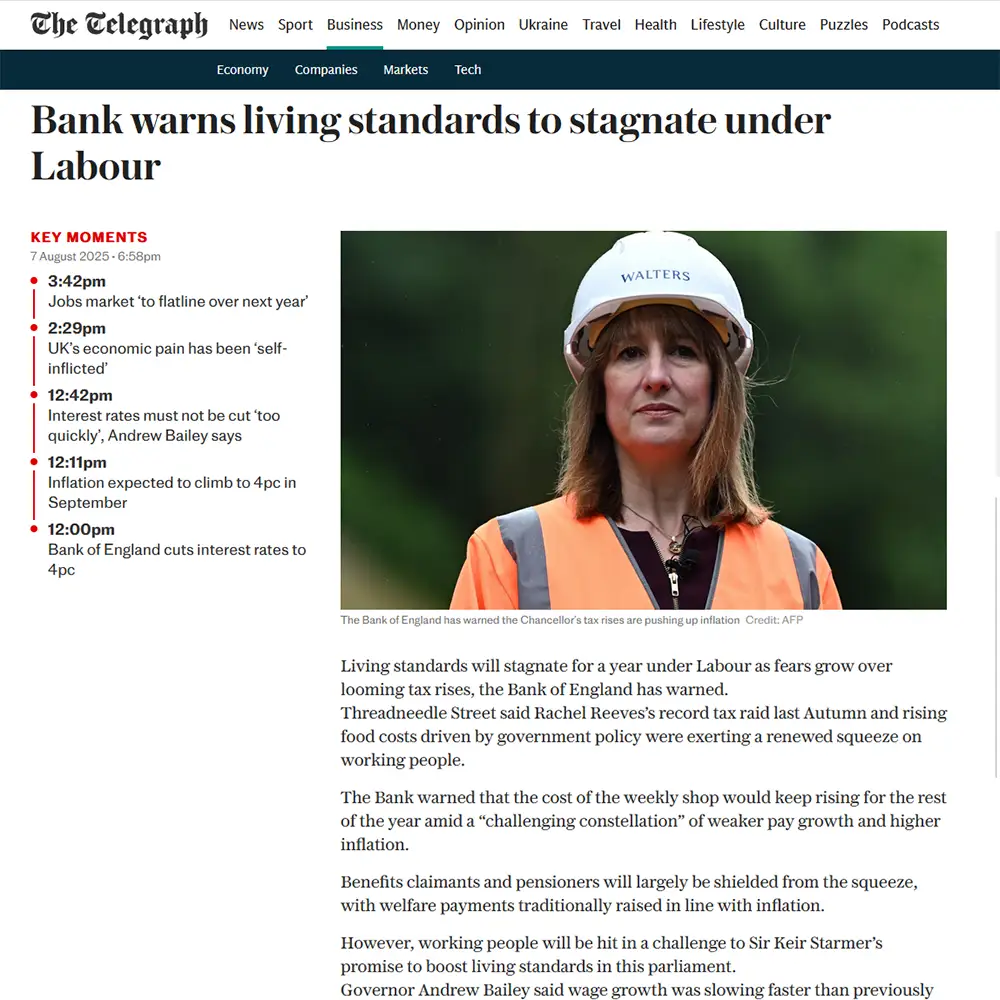

Telegraph – Read More

The Bank of England has raised interest rates to their highest level since 2008 in the wake of revelations that inflation remained uncomfortably high. The base rate rise from 4.25% to 4.5% represents the 12th successive increase in the cost of borrowing by the central bank since it started raising rates in December 2021 and follows similar moves by the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank. Reaction was swift as it confirmed earlier predictions. In terms of controlling inflation, it was unnecessary, according to a group of independent economists that shadow the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee. The Institute of Economic Affairs’ Shadow Monetary Policy Committee believe that the Bank is overfocusing on current inflation and not enough on the sharp reduction in the money supply – which will bring inflation under control within the next two years, as shown by the Bank’s official forecasts.

Director of Finance – Read More

Millions of Britons are facing painful increases in their mortgage costs after the Bank of England raised interest rates for the 12th time in a row to tackle “stubbornly high” inflation. The Bank rejected accusations that it had gone too far and was “overcorrecting” for the inflation crisis after the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted to hike the base interest rate from 4.25 per cent to 4.5 per cent. The central bank warned inflation is set to decline less rapidly this year than hoped because food price hikes have gone on longer than expected, partly due to the Ukraine war and poor harvests in Europe. Left-wing IPPR think tank said the Bank should have held off raising interest rates again, warning of a “continued increase in inequality”. And right-wing think tank the Institute of Economic Affairs also warned that the Bank was at risk of “overcorrecting”.

Independent – Read More

The central bank announced the decision to increase its rate by 0.25 per cent today with a hint that it could peak at 4.75 per cent by the end of 2023. With inflation remaining in the double figures despite the base rate rising for the 12 month in a row, some commentators wondered if it was time for the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee to change tack. Trevor Williams, chair of the Institute of Economic Affairs’ shadow Monetary Policy Committee and former chief economist at Lloyds Bank, echoed these views and said: “Just as the Bank of England failed to identify inflationary pressures at the tail end of the Covid-19 pandemic, they may be once again focusing too much on present inflation rather than long run trends. The sharp reduction in the money supply points towards inflation coming down quickly over the coming two years. “Inflation could still dip to around one per cent over the next two to three years and even after adjusting for the bank’s revised forecast suggesting stronger growth, it is expected to undershoot the two per cent target. This trajectory indicates interest rates need not go up any further.”

Mortgage Solutions – Read More

Global Mobility Report Q1 2023

Henley Passport Power: A Causal Link between Access and Growth

The Henley Passport Index (HPI) features significant insights into the economic benefits of visa-free access and the economic prospects of the countries and individuals involved. Let’s start by assessing the passport power of countries ranked by their share of global gross domestic product (GDP) versus the HPI, as shown in the firm’s latest research. Read the full press release here.

Read the full press release here.